http://rpseawright.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/is-the-yale-model-past-it/(Data numbers appears to be dating mid-2012, the last numbers available for US College endowment performance)

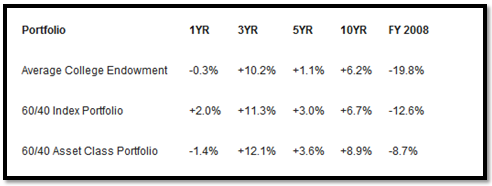

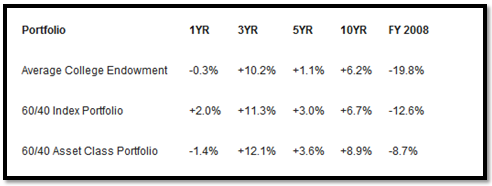

"A simple 60/40 portfolio invested 60 percent in an S&P 500 index fund and 40 percent in a fund tracking the Barclays Aggregate bond index would have gained 12.6 percent annually over the last three years and 2.8 percent over the last five years, as compared with 10.2 percent and 1.1 percent, respectively, for the average endowment"

"The available evidence provides a pretty good case for the idea that the Yale Model is past its peak due to overcrowding. A more traditional approach may simply make more sense, even if such an approach is decidedly less “sexy,” especially for those who don’t have Yale’s access and expertise."

Comments

I imagine that Swensen is ‘earning’ even more these days.

Yaledailynews.com

BY VIVIAN YEE

STAFF REPORTER

Friday, September 10, 2010

Yale’s endowment may have shed nearly a quarter of its value last year, but three of the men charged with managing it earned a combined $10.1 million in salary and benefits during the same time period, according to the University’s most recent tax filings.

As they have been for the past several years, Chief Investment Officer David Swensen GRD ’80 and his second-in-command, Dean Takahashi ’80 SOM ’83, were the two highest-paid employees at Yale in the 2008-’09 academic year, with investments director Alan Forman coming in fourth. Third on the list was University President Richard Levin, who, with $1.5 million in salary and benefits, made about a quarter more than he did the year before.

Swensen’s salary and benefits totaled $5.3 million last year, almost a quarter more than the $4.3 million he earned in the 2007-’08 academic year. His deputy, Takahashi, took home $3.5 million, a 35 percent raise from the year before.

What the filings do not make clear is how much exactly the investments officers took home in 2008-’09, since their compensation includes deferred bonuses they will be paid in the future as well as past deferred bonuses they have now been paid.

A look at some notable funds with $20B AUM, like Yale's endowment:

Performance shown relative to buy-and-hold balanced fund as of Dec 2012.

Note too the amount of annual fees generated by these funds. Even the relatively low-cost Windsor II fund charged $63M for the privilege of having Mr. Jim Barrow and his colleagues under-perform, including an SP500-like 37% drop in 2008.

In comparison, what is the annual fee for SPY on $20B? $18M.

So, while the Yale Daily News article grabbed my attention, it should probably have stated somewhere that outsourcing the endowment's management would likely cost much much more than what Mr. Swensen and his team are getting.

Not sure what to think of Mr. Seawright's site. Modesty and humility are two words that do not come to mind. But I book-marked it.

Note that M* has the 0.90 ER as "Below Average". So, to update the annual revenue generation of this fund for Fidelity:

Fee = ER/100 * AUM = $399M.

I must be miscalculating, because Fidelity simply wouldn't be taking $399M a year on $44.3B in AUM to generate average returns, right?

Thanks for the excellent reference.

All these types of reports consistently demonstrate how difficult a struggle it is to simply outfox a balanced Index portfolio.

Institutional investors should be the absolute cream of the crop with regard to the entire investment community. They have more resources, can hire a bevy of specialized sub-portfolio managers, and because of their pay structure should attract the most talented mangers even above mutual fund giants.

Yet over the longer timeframe, superior excess returns prove appallingly difficult to achieve. Persistence is the perennial challenge, and most fail the test. It is the case of talented investors battling other talented investors to a draw.

Overcrowding might indeed be the enemy for these institutional investors. I like to equate it more directly to a size impact effect, especially within the mutual fund sector.

I’m thinking now how performance suffered when star mutual fund managers attracted a huge inflow of monies when their earlier success became common knowledge. That happened in the go-go 1960s when Jerry Tsai’s Manhattan fund hit hard times as the size of his fund grew. He registered dismal later results before selling his operation. He died recently.

The same investment story was later repeated by Robert Sanborn with his Oakmark fund and with Peter Lynch with his Magellan fund. The size growth in all these instances meant that the manager was forced to buy larger amounts of his best ideas ( a form of overcrowding) that influenced prices, and/or divert money into their secondary idea category. Annual performance suffered in these cases.

To paraphrase financial writer Jonathan Clements observation: Performance travels on both an upward and downward escalator, but costs are a reliable constant. Costs persist; fund manager performance does not.

Best Wishes.

But to give the industry some credit, most of the funds available in the 1960-70's had loads of 8.5%, can you believe?

Today, fortunately, loads seem to be an exception. Vanguard helped pave way to lower fees. Expense is constantly flagged when high by M*. Many ETFs have extremely low fees as well.

So, maybe there is some hope that costs will continue to decrease, as markets demand it. A dream I have...