Objective

The fund pursues long-term growth by investing in 30-50 undervalued global stocks. Generally it avoids small cap caps, but can invest up to 30% in emerging and less developed markets. The managers look for four characteristics in their investments:

- A high quality business

- With a strong balance sheet

- Shareholder-focused management

- Selling for less than it’s worth.

The managers can hedge their currency exposure, though they did not do so until they confronted twin challenges to the Japanese yen: unattractive long-term fiscal position plus the tragedies of March 2011. The team then took the unusual step of hedging part of their exposure to the Japanese yen.

Adviser

Artisan Partners of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Artisan has five autonomous investment teams that oversee twelve distinct U.S., non-U.S. and global investment strategies. Artisan has been around since 1994. As of 3/31/2011 Artisan Partners had approximately $63 billion in assets under management (March 2011). That’s up from $10 billion in 2000. They advise the 12 Artisan funds, but only 6% of their assets come from retail investors. Update – Artisan Partners had approximately $57.1 billion in assets under management, as of 12/31/2011.

Manager

Daniel J. O’Keefe and David Samra, who have worked together since the late 1990s. Mr. O’Keefe co-manages this fund, Artisan International Value (ARTKX) and Artisan’s global value separate account portfolios. Before joining Artisan, he served as a research analyst for the Oakmark international funds and, earlier still, was a Morningstar analyst. Mr. Samra has the same responsibilities as Mr. O’Keefe and also came from Oakmark. Before Oakmark, he was a portfolio manager with Montgomery Asset Management, Global Equities Division (1993 – 1997). Messrs O’Keefe, Samra and their five analysts are headquartered in San Francisco. ARTKX earns Morningstar’s highest accolade: it’s an “analyst pick” (as of 04/11).

Management’s Stake in the Fund

Each of the managers has over $1 million here and over $1 million in Artisan International Value.

Opening date

December 10, 2007.

Minimum investment

$1000 for regular accounts, reduced to $50 for accounts with automatic investing plans. Artisan is one of the few firms who trust their investors enough to keep their investment minimums low and to waive them for folks willing to commit to the discipline of regular monthly or quarterly investments.

Expense ratio

1.5%, after waivers, on assets of $57 million (as of March 2011). Update – 1.5%, after waivers, on assets of $91 million (as of December 2011).

Comments

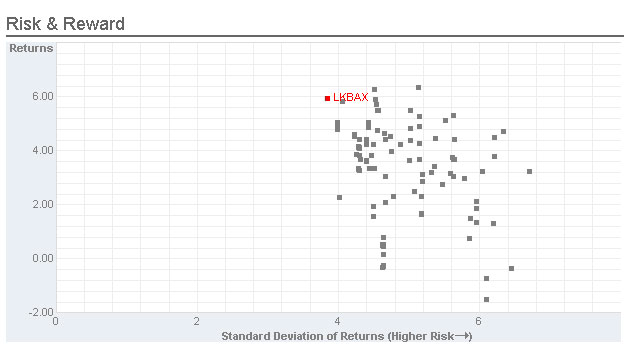

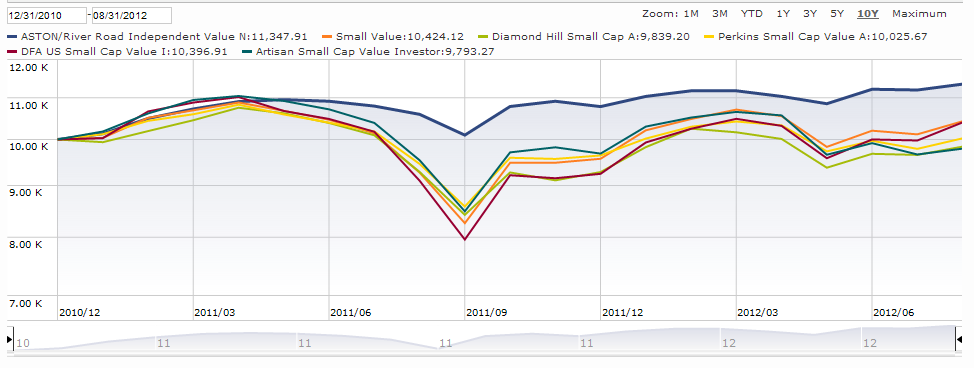

Artisan Global Value is the first “new” fund to earn the “star in the shadows” designation. My original new fund profile of it, written in February 2008, concluded: “Global is apt to be a fast starter, strong, disciplined but – as a result – streaky.” I have, so far, been wrong only about the predicted streakiness. The fund’s fast, strong and disciplined approach has translated into consistently superior returns from inception, both in absolute and risk-adjusted terms. Its shareholders have clearly gotten their money’s worth, and more.

What are they doing right?

Two things strike me. First, they are as interested in the quality of the business as in the cost of the stock. O’Keefe and Samra work to escape the typical value trap (“buy it! It’s incredibly cheap!”) by looking at the future of the business – which also implies understanding the firm’s exposure to various currencies and national politics – and at the strength of its management team. One of the factors limiting the fund’s direct exposure to emerging markets stocks is the difficulty of finding sufficiently high quality firms and consistently shareholder-focused management teams. If they have faith in the firm and its management, they’ll buy and patiently wait for other investors to catch up.

Second, the fund is sector agnostic. Some funds, often closet indexes, formally attempt to maintain sector weights that mirror their benchmarks. Others achieve the same effect by organizing their research and research teams by industry; that is, there’s a “tech analyst” or “an automotive analyst.” Mr. O’Keefe argues that once you hire a financial industries analyst, you’ll always have someone advocating for inclusion of their particular sector despite the fact that even the best company in a bad sector might well be a bad investment. ARTGX is staffed by “research generalists,” able to look at options across a range of sectors (often within a particular geographic region) and come up with the best ideas regardless of industry. That independence is reflected in the fact that, in eight of ten industry sectors, ARTGX’s position is vastly different than its benchmark’s. Too, it explains part of the fund’s excellent performance during the 2008 debacle. During the third quarter of 2008, the fund’s peers dropped 18% and the international benchmark plummeted 20%. Artisan, in contrast, lost 3.5% because the fund avoided highly-leveraged companies, almost all banks among them.

Why, then, are there so few shareholders?

Manager Dan O’Keefe offered two answers. First, advisors (and presumably many retail investors) seem uncomfortable with “global” funds. Because they cannot control the fund’s asset allocation, such funds mess up their carefully constructed plans. As a result, many prefer picking their international and domestic exposure separately. O’Keefe argues that this concern is misplaced, since the meaningful question is neither “where is the firm’s headquarters” or “on which stock exchange does this stock trade” (the typical dividers for domestic/international stocks) but, instead, “where is this company making its money?” Colgate-Palmolive (CL) is headquartered in the U.S. but generates less than a fifth of its sales here. Over half of its sales come from its emerging markets operations, and those are growing at four times the rate of its domestic or developed international market shares. (ARTGX does not hold CL as of 3/31/11.) His hope is that opinion-leaders like Morningstar will eventually shift their classifications to reflect an earnings or revenue focus rather than a domicile one.

Second, the small size is misleading. The vast majority of the assets invested in Artisan’s Global Value Strategy, roughly $3.5 billion, are institutional money in private accounts. Those investors are more comfortable with giving the managers broad discretion and their presence is important to retail investors as well: the management team is configured for investing billions and even a tripling of the mutual fund’s assets will not particularly challenge their strategy’s capacity.

What are the reasons to be cautious?

There are three aspects of the fund worth pondering. First, the expense ratio (1.50%) is above average even after expense waivers. Even fully-grown, the fund’s expenses are likely to be in the 1.4% range (average for Artisan). Second, the fund offers limited direct exposure to emerging markets. While it could invest up to 30%, it has never invested more than 9% and, since late-2009, has had zero. Many of the multinationals in its portfolio do give it exposure to those economies and consumers. Third, the fund offers no exposure to small cap stocks. Its minimum threshold for a stock purchase is a $2 billion market cap. That said, the fund does have an unusually high number of mid-cap stocks.

Bottom Line

On whole, Artisan Global Value offers a management team that is as deep, disciplined and consistent as any around. They bring an enormous amount of experience and an admirable track record stretching back to 1997. Like all of the Artisan funds, it is risk-conscious and embedded in a shareholder-friendly culture. There are few better offerings in the global fund realm.

Fund website

Update – December 31, 2011 (4Q) – Fact Sheet (pdf)

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2011. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact [email protected].