By Charles Boccadoro

This fund has been liquidated.

Objective and Strategy

The AdvisorShares TrimTabs Float Shrink ETF (TTFS) objective is to generate long-term gains in excess of the Russell 3000 Index, which measures the performance of the largest 3000 U.S. companies representing approximately 98% of the investable U.S. equity market.

The fund’s actively managed strategy is to exploit supply-and-demand opportunities created when companies repurchase shares in a manner deemed beneficial to shareholders. More specifically, the fund seeks to own companies that are buying-back shares with free cash flow while not increasing debt. Such buy-backs benefit shareholders in a couple ways. First, they reduce float, which is the number of regular shares available to the public for trading. “All else being equal,” the reasoning goes, “if the same money is chasing a smaller float, then the share price increases.” Second, they signal that top company insiders see value in their own stock, opportunistically at least.

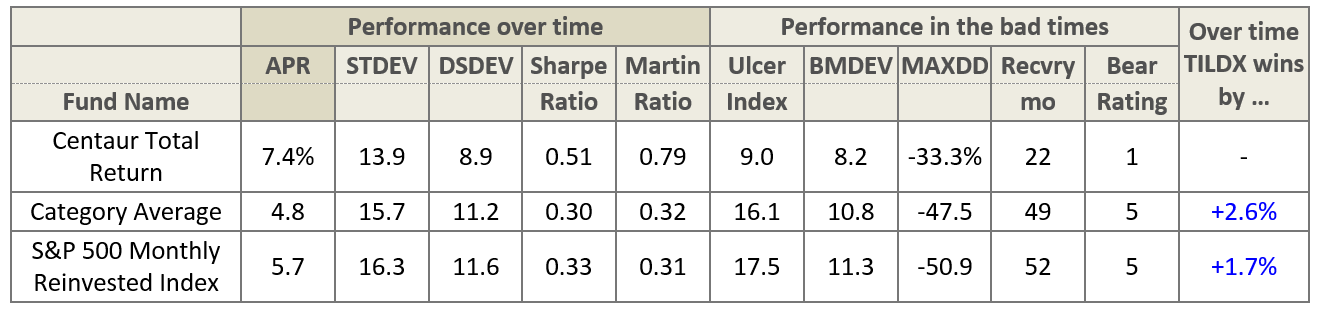

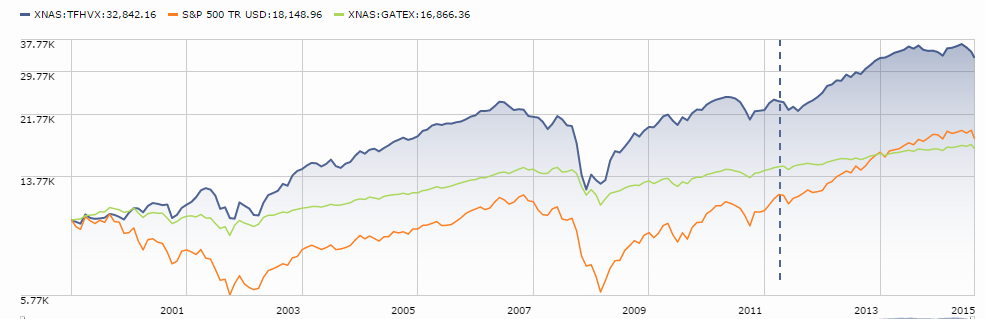

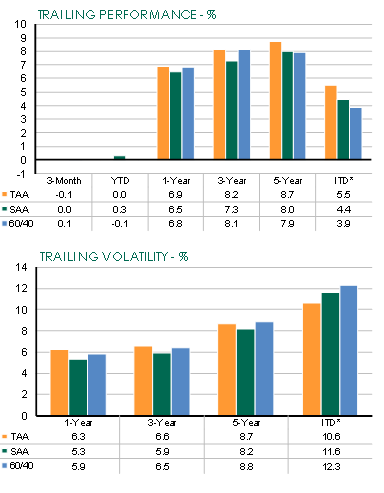

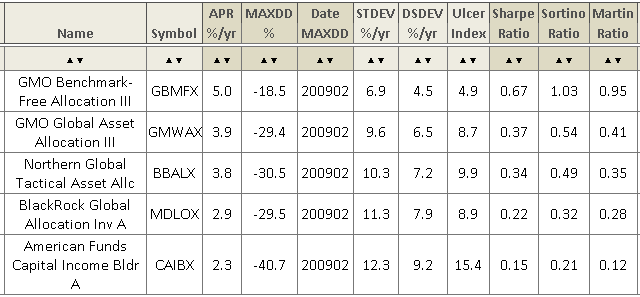

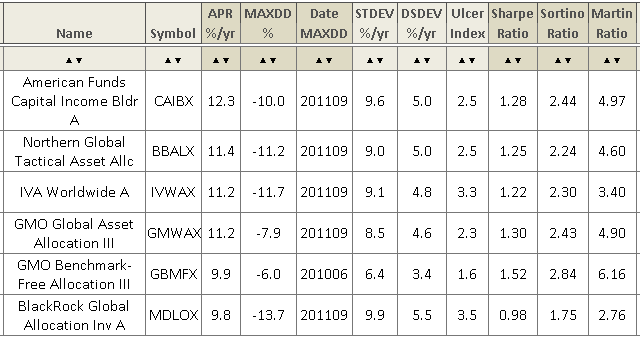

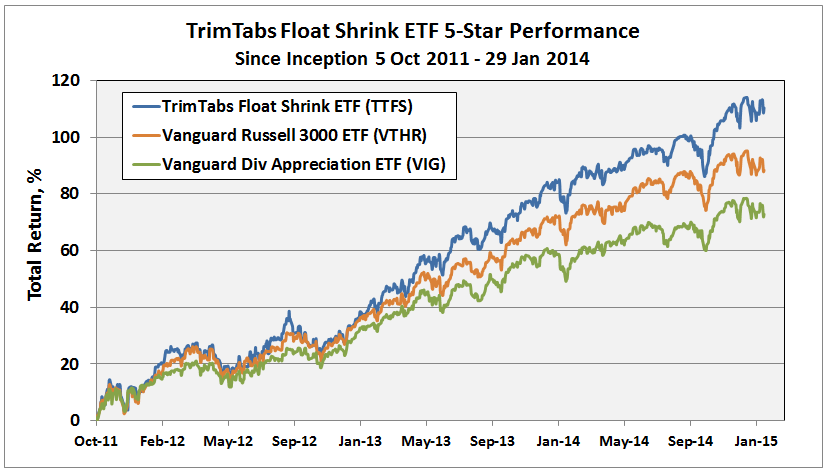

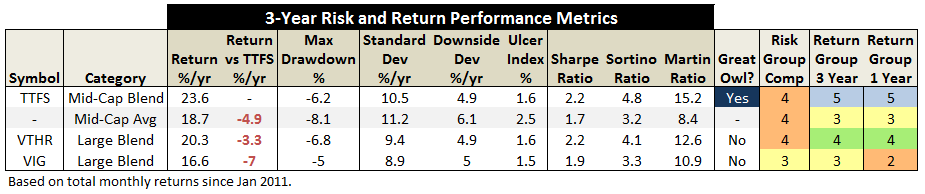

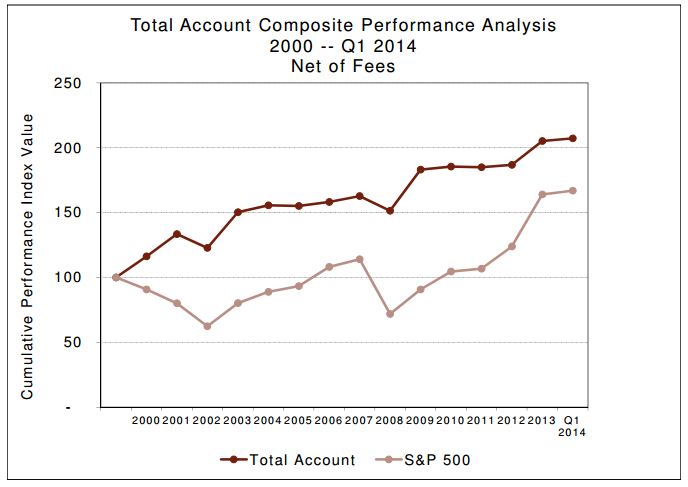

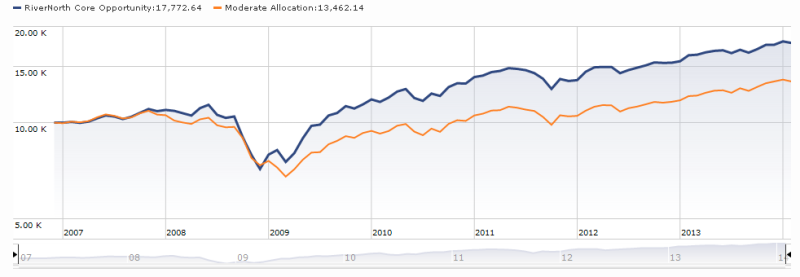

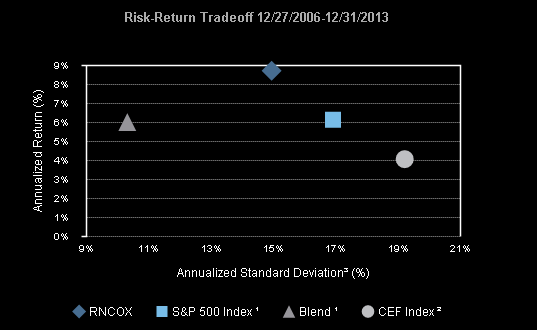

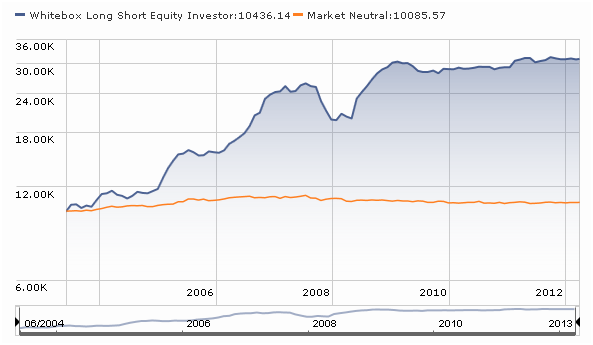

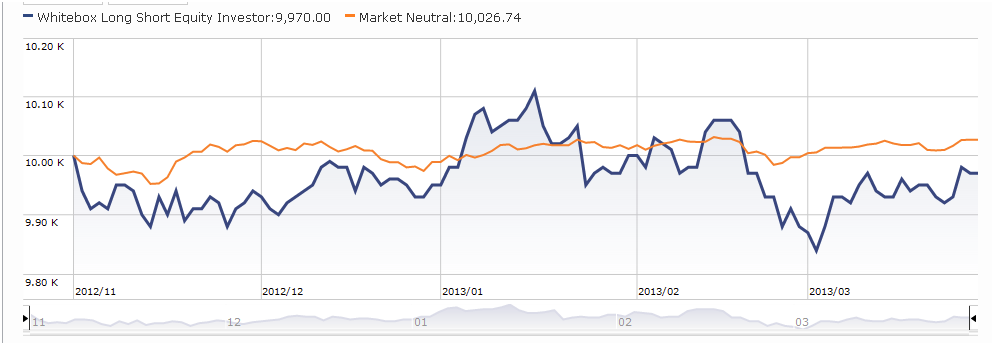

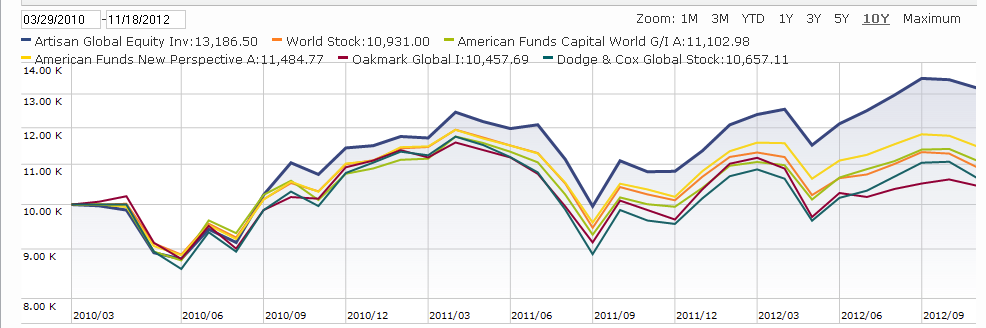

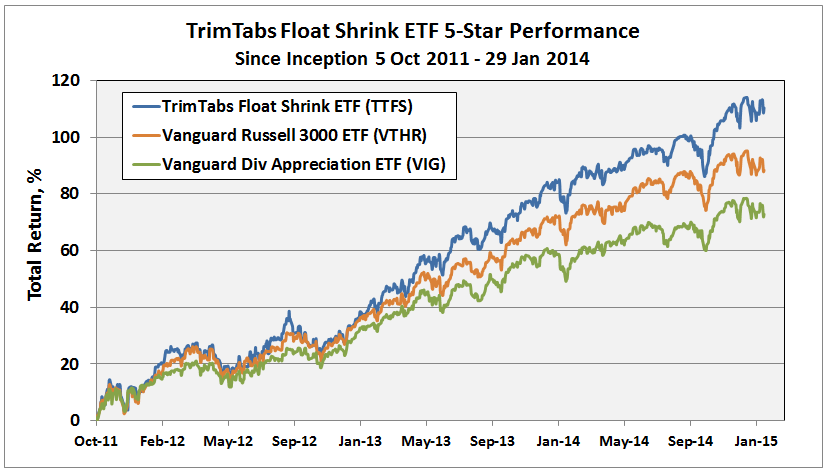

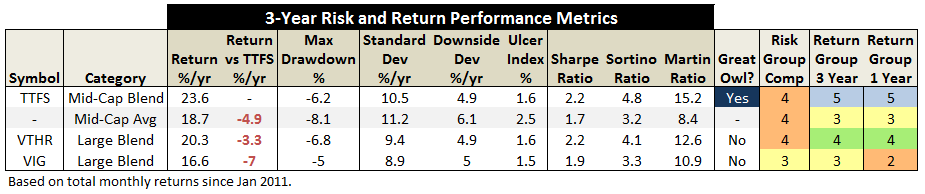

So far, the strategy has delivered superbly. Last November, TTFS past its three year mark and received Morningstar’s 5-Star quantitative rating and MFO’s Great Owl designation. TTFS rewarded investors with significantly higher absolute return and lower volatility than its category average of 134 peers. It also bested Vanguard’s Russell 3000 Index ETF (VTHR) and Vanguard’s Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIG). Here’s snapshot of return since inception with accompanying table of 3-year metrics (ref. Ratings Definitions):

Adviser

AdvisorShares is the fund adviser for TTFS. It’s based in Bethesda, Maryland. It maintains the statutory trust for a lineup of 20 disparate ETFs with an almost equal number of subadvisers. The ETFs have collectively gathered about $1.3B in assets. All 20 are under five years of age. Of the 10 at the 3-year mark, 9 have delivered average to bottom quintile performance. The younger 10 have similarly dismal numbers at the 1-year mark or since inception. The firm generally charges too much and delivers too little for me to recommend. There is perhaps one exception.

TrimTabs Asset Management, LLC is the subadviser and portfolio manager for TTFS. A small company with half a dozen employees located in Salsilitdo, California, a waterfront town just north of the Golden Gate Bridge. The subadviser manages about $184M AUM, all through its one ETF. It has no separately managed accounts.

The subadviser is a subsidiary of TrimTabs Investment Research, Inc., which tracks money flows of stock markets, mutual funds, hedge funds, and commodity traders, as well as corporate buy-backs, new offerings, and insider trading. The research company sells its data and research reports through paid subscription to hedge funds and financial institutions. It briefly ran its own hedge fund in 2008, called TrimTabs Absolute Return Fund, LP.

The name “trim tab” refers to the small control effector found on the main rudder of a ship or plane. Like the trim tab helps the main rudder steer its vehicle through application of a small force at the right location, so too does the company hope to aid its subscribers and investors through insight provided by its data into market behavior. The company hopes TTFS’s recent success will enable it to offer new ETFs as an adviser proper.

Managers

The portfolio managers are Charles Biderman and Minyi Chen.

Charles Biderman founded TrimTabs in 1990 and remains its CEO. He holds a B.A. from Brooklyn College and an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School. He co-authored the Wiley book “TrimTabs Investing: Using Liquidity Theory to Beat the Stock Market” in 2005. It scores mixed reviews, but it forms the basis for principles followed by TTFS.

His bio touts that he is “interviewed regularly on CNBC and Bloomberg and is quoted frequently in the financial media…” He does indeed appear to be the TV media spokesman and frontman for the firm and ETF. His views are contrarian and his appearances seem to be a flashpoint for debate. But his record at predicting the future based on those views is spotty at best. A few examples:

- In September 2006 on Squawk Box, he was bullish on US economy based on strong take home pay and company buy-backs.

- In September of 2007 on CNBC, he predicted the credit problems were short-lived.

- In summer of 2010, he warned multiple times of an imminent collapse in US market (eg., Fox, CNBC, and via webpost).

- In 2012, he again predicted a 50% market collapse.

More recently on Squawk Box, his contrarian views on what drives markets seemed to resonate with Joe Kernen’s own speculation about potential for conspiracy theory regarding wealth distribution and the Fed’s role in it.

He maintains Biderman’s Money Blog and the online course Biderman’s Practices of Success, which are based upon ontological training (the science of being present to life). Course proceeds go to support foster youth. Both activities are based on Mr. Biderman’s personal opinions and do not reflect the opinions of TrimTabs proper.

Minyi Chen, on the other hand, appears to be the ideal inside person, handling day-to-day operation of the ETF and answering more detailed questions on the fund’s back-testing and methodology. He appears to be the “yin” and to his co-manager’s “yang.” He joined TrimTabs Investment Research in 2008 and serves as its Chief Operating Officer and Chief Financial Officer. Mr. Chen holds a B.A. from Shanghai International Studies University in China and a M.B.A from Northwestern Polytechnic University in California. He is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) charterholder. He speaks English and Chinese.

I first interviewed him last fall during the Morningstar ETF Conference. He’s soft spoken with a reserved but confident demeanor. He answers questions about the fund in direct and simple terms. He explains that there is “no human input” in the implementation of TTFS’s strategy. It follows a stable, rules-based methodology. When asked about the buzz surrounding “strategic beta” at the conference, he stated “I would rather have strategic alpha.”

Strategy capacity and closure

Minyi estimates the fund’s capacity at $5B and is only limited by trading volume of the underlying stocks. He explains that the fund invests in 100 stocks from the Russell 3000 membership, which has an average market cap of $110B and a median market cap of $1.5B. The fund must be able to buy-and-sell stocks that trade frequently enough to not be adversely impacted with trades of 1/100th of its AUM. When the fund launched in 2011 with $2M in AUM, virtually all 3000 stocks traded at sufficient liquidity. At today’s AUM, which is closer to $200M, 25-30 of the benchmark’s more illiquid stocks can’t handle a $2M daily buy/sell order and are screened-out. ETFs can’t be closed, but the larger the AUM, the more restricted the application of its strategy…but any significant impact is still a long way off.

Active share

TrimTabs does not maintain an “active share” statistic, which measures the degree to which a fund’s portfolio differs from the holdings of its benchmark portfolio. Given that TTFS’s benchmark is the Russell 3000 and cap-weighted, I’d be surprised if its active share was not near 80% or higher.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

As of December, 2014, the SAI filing indicates Mr. Biderman has between $100-500K and Mr. Chen between $10-50K in the fund. Direct correspondence with the firm indicates that the actual levels are closer to the minimums of these brackets. The adviser appears to have only one trustee with a stake in the fund somewhere between $1 and $10K.

On Mr. Biderman’s website, he states “I am someone who started with nothing three times and created three multi-million dollar net worths.” If accurate, his modest stake in TTFS gives pause. The much younger Mr. Chen states that his investment is a substantial part of his 401K. As for AdvisorShares, its consistent lack of direct investment by its interested and independent trustees in any of the firm’s offerings never ceases to disappointment.

Opening date

October 04, 2011. TTFS’s strong performance since inception has attracted close to $200M, an impressive accomplishment given the increasingly crowded ETF market. Among actively managed ETFs across Moningstar’s 3×3 category box, TTFS is second in AUM only to Cambria Shareholder Yield ETF (SYLD), and has more than twice the AUM of its next closest competitor iShares Enhanced US Large-Cap (IELG).

Minimum investment

TTFS is an ETF, which means it trades like a stock. At market close on January 29, 2015, the share price was $55.07.

Expense ratio

0.99%. There is no 12b-1 fee. The annual 0.99% reflects a contractually agreed cap, but is still above average for actively managed ETFs.

The fee to the subadviser is 0.64%.

Minyi cannot envision its expense ratio ever exceeding 0.99%; in fact, he states that as AUM increases, TrimTabs will approach AdvisorShares to reduce fee. He also states that TrimTabs avoids conflict of interest by having no soft dollars in the TTFS fee structure. [See SEC Report and recent ValueShares US Quantitative Value (QVAL) profile.]

Comments

Many legendary investors, like Howard Marks, believe that the greatest gains come from buying when everybody else is selling. Since doing so can be extremely uncomfortable, investors must have a confident view of intrinsic value calculation. While this sounds reasonable, comforting, and even admirable, the folks at TrimTabs believe that such a calculation is simply not possible. They argue:

Most fundamental investment approaches, such as the discounted cash flow method, attempt to calculate a company’s intrinsic value. Investors attempt to exploit discrepancies between intrinsic value and the market value. The problem with these approaches is that it is impossible to know exactly what intrinsic value is.

If you have ever worked through discounted cash flow valuation methods, like those described in Aswath Damorarn’s definitive Wiley book “Investment Valuation…Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset,” you can quickly see their point. With so many variables and assumptions involved, including estimates of terminal value 10 years out, the “fair value” calculation can become 1) simply a means to rationalize the price you are willing to pay, and 2) a futile exercise similar to measuring a marshmallow with a micrometer.

In his many interviews, Mr. Biderman argues that “valuation has never been a good predictor of stock price.” Vanguard’s 2012 study “Forecasting stock returns: What signals matter, and what do they say now?” seems to back his position (the study was highlighted by MJG during a debate on the MFO Discussion Board):

Although valuations have been the most useful measure…even they have performed modestly, leaving nearly 60% of the variation in long-term returns unexplained. What predictive power valuations do have is further clouded by our observation that different valuations, although statistically equivalent, can produce different “point forecasts” for future stock returns.

Minyi uses the recent price collapse in oil to illustrate the firm’s position that “instead of guessing about intrinsic value, we contend that the prices of stocks, like the prices of other tradable goods, are set by the underlying conditions of supply and demand.”

The three principles TrimTabs uses to guide its TTFS portfolio selection follow:

- Float shrink: Invest in companies that reduce their float over time. Most companies shrink the float through stock buybacks, but companies can also reduce the float by taking other actions, such as reverse stock splits or spin-offs.

- Free cash flow: Invest in companies that shrink the float because their underlying business is profitable, not because they are divesting assets.

- Leverage: Do not invest in companies that simply swap equity for debt. Such exchanges do not add real value because the risk of equity capital rises when the proportion of debt capital grows.

To implement the strategy, TrimTabs calculates a so-called “liquidity score” for each of the Russell 3000 companies, after screening out those whose trading volumes are too low. Their back-tests from September 20, 2000 through November 17, 2011 showed that risk-adjusted returns were strongest when the composite liquidity score used 60% weight on float, 30% weight on free cash flow, and 10% weight on leverage. The three input metrics are measured over the most recent 120-day trading window.

In a nutshell, start with the 3000 names, screen-out least liquid stocks based on current AUM, rank the remaining with a composite liquidity score, invest in the top 100 names equal dollar amounts.

A few other considerations…

TrimTabs argues that their expertise, their foundation and edge, comes from two decades of experience researching money flows in markets and providing these data to hedge funds, investment banks, and trading desks. Today, TrimTabs is able to rapidly and accurately distill this information, which comes from 10K and 10Q filings, company announcements, and other sources, into an actionable ETF strategy.

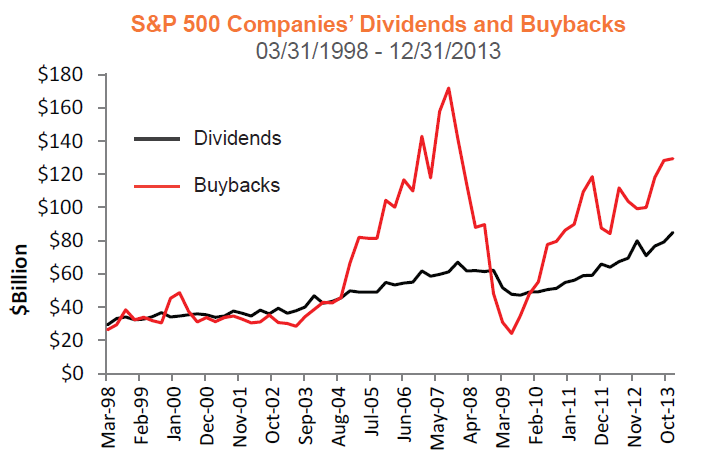

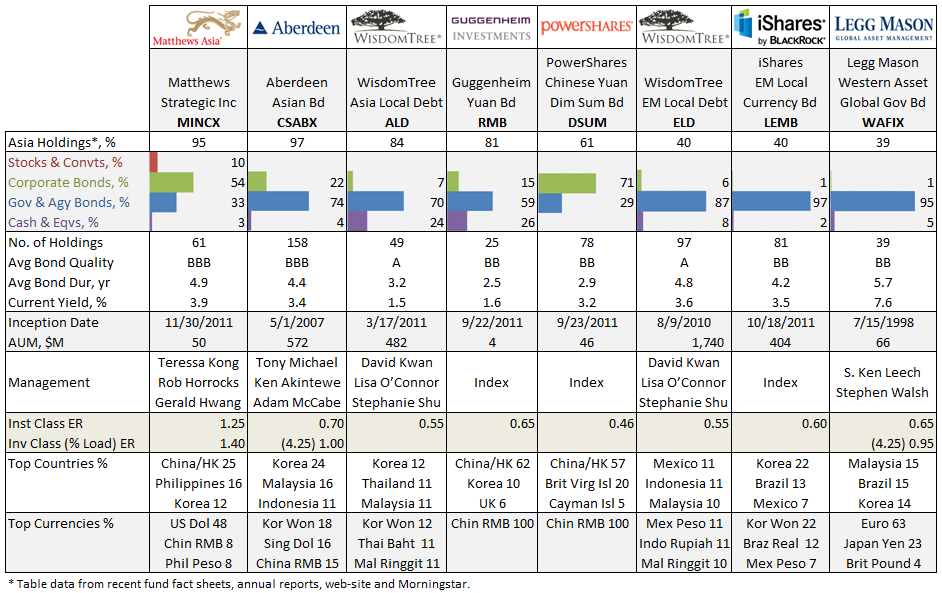

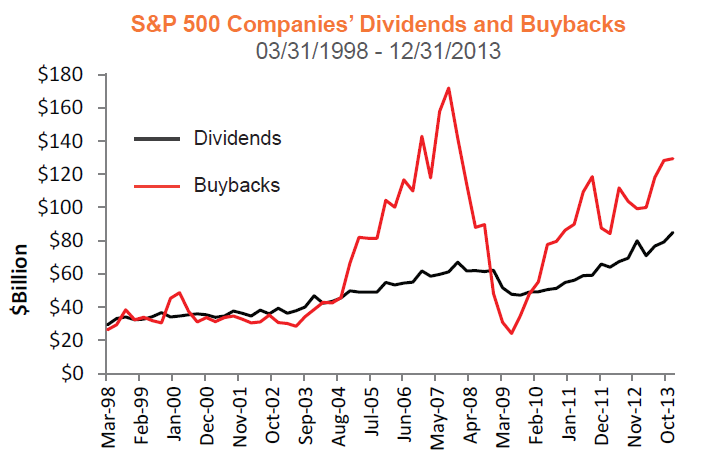

Since the late 1990’s, companies have been spending more of their free cash flow on buy-back than dividends. In his 2013 book “Shareholder Yield: A Better Approach to Dividend Investing,” Mebane Faber attributes some of the rational to SEC Rule 10b-18 established in 1982, which provides safe harbor for firms conducting share repurchases from stock manipulation charges. More recently, Mr. Biderman argues that the Fed’s zero interest policy encourages buy-backs and that companies are not seeing enough demand to invest instead in capital expenditure. Whatever the motivation, there is no arguing that buy-backs have become the norm and reducing float raises earnings per share. Here is a plot from a recent TrimTabs white paper that compares quarterly dividends and buybacks since 1998:

In a table of S&P 500 buy-backs provided by TrimTabs when requesting an interview before the Morningstar conference, about 300 companies (more than half) had reduced float during the previous year. Some 15 had reduced float by more than 10%, including CBS, Viacom (VIAB), ADT, Hess (HES), Corning (GLW), FedEx (FDX) and Northrop Grumman (NOC). Other big names with healthy buy-backs were Kellogg (K), Weyerhaeuser (WY), Travelers (TRV), Gap (GPS), IBM, Coca-Cola (CCE), Dollar Tree (DLTR), Express Scripts (ESRX) and WellPoint (WLP).

The firm believes metrics like float shrink, free cash flow, and leverage are less subject to accounting manipulation than other metrics used in traditional fundamental analysis; furthermore, companies that can buy-back shares, while simultaneously increasing free cash flow and decreasing debt are essentially golden.

Minyi explains that the strategy pursues companies with the highest composite liquidity score regardless of market cap or sector diversification, because “that’s where the alpha is.” For example, as of month ending December 2014, the portfolio was heavy consumer discretionary and light energy versus the benchmark. (The methodology does impose a 25% ultimate sector concentration limit for regulatory reasons, but that limit has never been reached since inception or in back-tests.) Similarly, TTFS held more mid-cap companies that its benchmark.

The turnover, while reducing as buy-backs increase, is high. It was 200% in 2014, down from 290% in 2013. But ETFs seem to enjoy a more friendly tax treatment than mutual funds, since they create and redeem shares with in-kind transactions that are not considered sales. (It’s something I still do not completely understand.) Sure enough, TTFS had zero short- and long-term cap-gains distributions for 2014.

Bottom Line

TTFS employs a rather unique and unconventional strategy that seems to have tapped current trends in the US stock market. It’s enabled by years of research in monitoring and providing data on money flows of markets.

Critics of the approach argue that buy-backs are not always a prudent use of capital, as evidenced by the massive amount of buy-backs in 2007 at elevated prices. And, as impressive as this young fund’s performance has been, it has existed only during bull market conditions.

I find the strategy intriguing and Minyi Chen instills confidence that it’s prosecuted in a transparent, easily understood and pragmatic manner. But the fund’s formal advisor is uninspired and only provides a drag on performance by adding an additional level of fees. There appears to be little “skin in the game” among stakeholders. And the fund’s most public spokesman warns often of imminent market collapse, seemingly undermining company attempts to grow AUM in the long-only portfolio.

Some investors care only about “listening to the market” in order to make money. They could care less about more qualitative assessments of a fund’s merits, like parent company, expenses, stewardship, or even risk-adjusted measures. A classic book on the topic is Ned Davis’ “Being Right or Making Money.”

So far, TTFS is making money for its shareholders.

I for one will wait with interest to see how the subadviser evolves to take advantage of its recent success.

Fund website

AdvisorShares maintains a webpage for TTFS here. To get quarterly commentaries, free registration is required. TrimTabs website offers little insight and is more geared toward selling database and newsletter subscriptions.

Fact Sheet

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2015. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact us.