Objective and strategy

LS Opportunity Fund pursues three goals: preserving capital, delivering above-market returns and managing volatility. “The secret,” says manager John Gillespie, “is to avoid large losses.” They invest, both long and short, in individual stocks; they do not short “the market,” they don’t use esoteric options and they don’t typically use ETFs. They normally will have 20-40 short positions and 50-70 long ones. The long portfolio is both all-cap and value-oriented, both of which are fairly rare. The short portfolio targets firms with weak or deteriorating fundamentals and unattractive valuations. They use pair-traded investments to reduce volatility and sector risk.

Adviser

Long Short Advisors, which was founded in 2010 as a way of making the ICAP hedge fund strategy available to retail investors. ICAP sub-advised this fund from 2010 until May, 2015. Prospector Partners LLC became the sub-advisor at the end of May, 2015. Prospector employs nine investment professionals and manages about $600 million through private partnerships, three funds and a couple of separately-managed accounts.

Manager

John Gillespie, Kevin O’Brien and Jason Kish. Mr. Gillespie worked for T. Rowe Price from 1986 – 1997, beginning as an analyst then managing Growth Stock (PRGFX) from 1994-1996 and New Age Media (a closed-end fund that morphed into Media & Telecommunications (PRMTX) from 1994-1997, after which he left to found Prospector Partners. Mr. Kish joined Prospector in 1997. Mr. O’Brien joined Prospector in 2003; prior to that he was an analyst and co-manager for Neuberger Berman Genesis Fund (NBGNX) and White Mountain Advisors. The team co-manages the Prospector Partners funds.

Strategy capacity and closure

$2 billion. The strategy currently holds $300 million.

Management’s stake in the fund

The managers just assumed responsibility for the fund in May 2015, shortly before the date of the Statement of Additional Information. At that point, two of the three managers had been $100,000 – $500,000 invested in the fund. Collectively they have “significant personal investments” in the strategy, beyond those in the mutual fund.

Opening date

The fund launched in September 2010, but with a different sub-adviser and strategy. The Prospector Partners took over on May 28, 2015; as a practical matter, this became a new fund on that date. Prospector has been managing the underlying strategy since 1997.

Minimum investment

$5,000.

Expense ratio

1.95% after waivers on assets of $25 million, as of February 2016.

Comments

In May 2015, circumstances forced Long-Short Advisors (LSA) to hit the reset button on their only mutual fund. The fund had been managed since inception by Independence Capital Asset Partners (ICAP), side by side with ICAP QP Absolute Return L.P., ICAP’s hedge fund. Unexpectedly, Jim Hillary, ICAP’s founder decided to retire from asset management, shutter the firm and liquidate his hedge fund. That left LSA with a hard decision: close the fund that was an extension of Mr. Hillary’s vision or find a new team to manage it.

They chose the latter and seem to have chosen well.

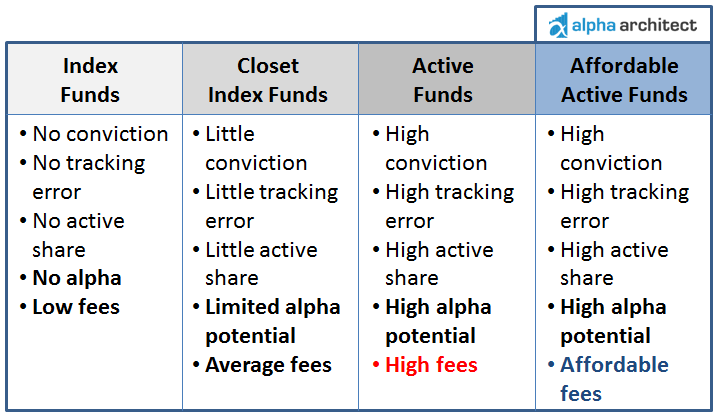

The phrase “long-short portfolio” covers a bunch of very diverse strategies. The purest form is this: find the most attractive stocks and reward them by buying them, then find the least attractive and punish them by shorting them. The hope is that, if the market falls, the attractive stocks will fall by a lot less than the whole market while the rotten ones fall by a lot more. If that happens, you might make more money on your short positions than you lose on your long ones and the portfolio prospers. Many funds labeled as “long-short” by Morningstar do not follow that script: some use ETFs to invest in or short entire market segments, some use futures contracts to achieve their short position, many hedge using buy-write options while some are simply misplaced “liquid alternatives” funds that get labeled “long short” for the lack of a better option. Here’s the takeaway: few funds in the “long-short” category actually invest, long and short, in individual stocks. By LSA’s estimation, there are about 30.

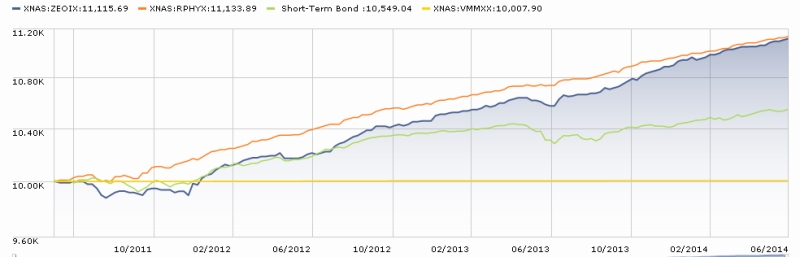

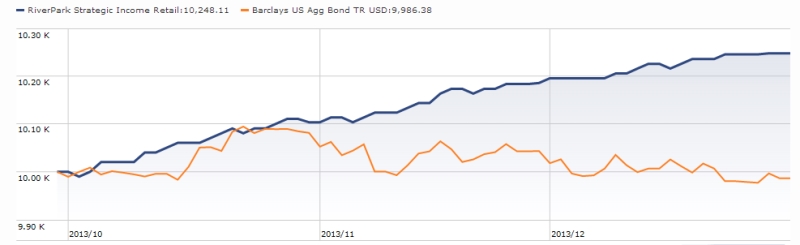

The argument for a long-short fund is simple. Most investors who want to reduce their portfolio’s volatility add bonds, in hopes that they’re lightly correlated to stocks and less volatile than them. The simplest manifestation of that strategy is a 60/40 balanced funds; 60% large cap stocks, 40% investment grade bonds. Such strategies are simple, cheap and have paid off historically.

Why complicate matters by introducing shorting? Research provided by Long Short Advisors and others makes two important points:

- The bond market is a potential nightmare. Over the past 30 years, steadily falling interest rates have made bonds look like a risk-free option. They are not. Domestic interest rates have bottomed near zero; rising rates drive bond prices down. Structural changes in the bond markets, the side effect of well-intentioned government reforms, have made the bond market more fragile, less liquid and more subject to disruption than it’s been in any point in living memory. In early 2016, both GMO and Vanguard projected that the real returns from investment-grade bonds over the next five to ten years will be somewhere between zero and negative 1.5% annually.

- Even assuming “normal” markets, long-short strategies are a better option than 60/40 ones. Between 1998 and 2014, an index of long/short equity hedge funds has outperformed a simple 60/40 allocation with no material change in risk.

In short, a skilled long-short manager can offer more upside and less downside than either a pure stock portfolio or a stock/bond hybrid one.

The argument for LS Opportunity is simpler. Most long/short managers have limited experience either with shorting stocks or with mutual funds as an investment vehicle. More and more long/short funds are entering the market with managers whose ability is undocumented and whose prospects are speculative. Given the complexity and cost of the strategy, I’d avoid managers-with-training-wheels.

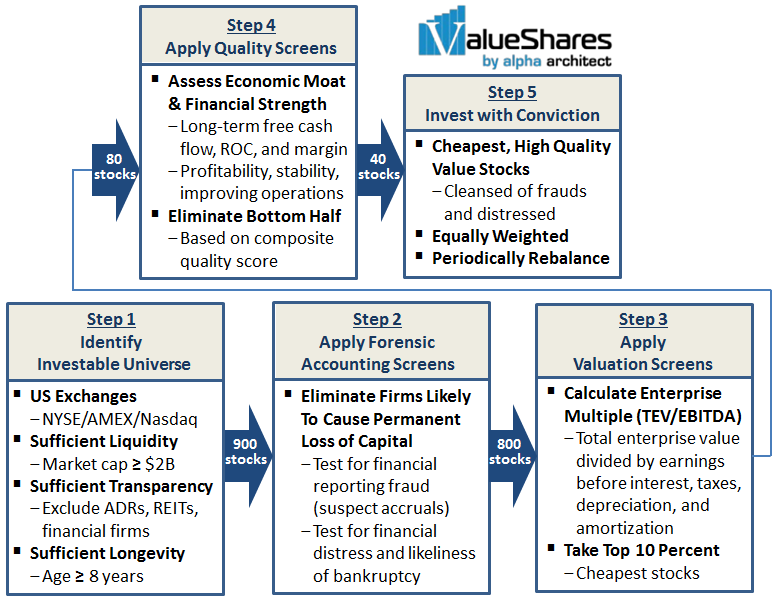

Prospector Partners, in contrast, has a long and excellent record of long-short investing. The firm was founded in 1997 by professionals who had first-rate experience as mutual fund managers. They have a clear, clearly-articulated investment discipline; they work from the bottom up, starting with measures of free cash flow yield. FCF is like earnings, in that it measures a firm’s economic health. It is unlike earnings in that it’s hard to rig; that is, the “earnings” that go into a stock’s P/E ratio are subject to an awful lot of gaming by management while the simpler free cash flow remains much cleaner. So, start with healthy firms, assess the health of their industries, look for evidence of management that uses capital wisely, then create a relatively concentrated portfolio of 50-70 stocks with the majority of the assets typically in the top 20 names. The fact that they’ve been developing deeper understanding of specific industries for 20 years while many competitors sort of fly-by using quant screens and quick trades, allows Prospector “to capitalize on informational vacuums in Insurance, Consumer, Utilities, and Banks.” They seem to have particular strength in property and casualty insurance, an arena “that’s consistently seen disruption and opportunity over time.”

The short portfolio is a smaller number of weak companies in crumbling industries. The fact that the management team is stable, risk-conscious and deeply invested in the strategy, helps strengthen the argument for their ability to repeat their accomplishments.

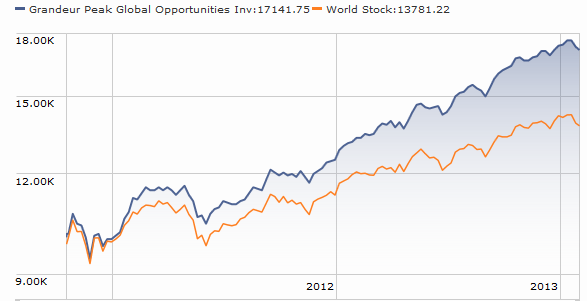

The LSOFX portfolio is built to parallel Prospector Partners’ hedge fund, whose historical returns are treated as prior related performance and disclosed in the prospectus of LSOFX. Here are the highlights:

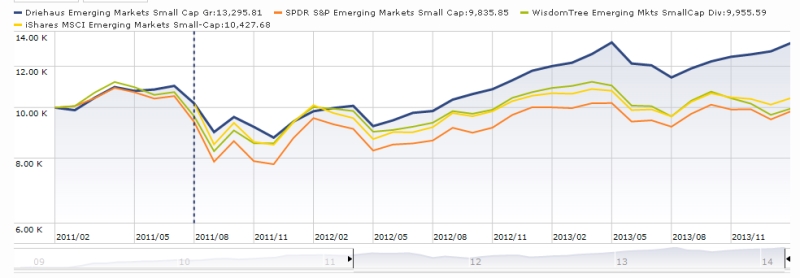

- From inception through mid-2015, a $1,000 investment in the Partner’s strategy grew to $5000 while an investing in the S&P 500 would have grown to $3000 and in the average long-short hedge fund (HFRI Equity Hedge), to $4000.

- During the dot-com crash from 2000-02, their hedge fund made money each year while the S&P 500 lost 9, 12, and 22%. That reflects, in part, the managers’ preference for a value-oriented investment style during a period when anything linked with tech got eviscerated.

- During the market panic from 2007-09, the S&P 500 fell by 3% or more in nine (of 18) months. The fund outperformed the market in every one of those months, by an average of 476 basis points per month.

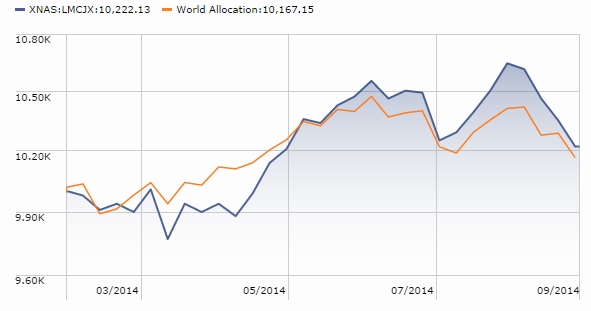

Since taking responsibility for LSOFX, the managers have provided solid performance and consistent protection. The market has been flat or down in six of the eight months since the changeover. LSOFX has outperformed the market in five of those six months. And it has handily outperformed both the S&P 500 and its nominal long-short peers. From June 1, 2015 to the middle of February 2016, LSOFX lost 2.1% in value while the S&P 500 dropped 7.4% and the average long-short fund lost 9.0%.

Bottom Line

Even the best long-short funds aren’t magic. They don’t pretend to be market-neutral, so they’ll often decline as the stock market does. And they’re not designed to keep up with a rampaging bull, so they’ll lag when long-only investors are pocketing 20 or 30% a year. And that’s okay. At their best, these are funds designed to mute the market’s gyrations, making them bearable for you. That, in turn, allows you to become a better, more committed long-term investor. The evidence available to us suggests that LSA has found a good partner for you: value-oriented, time-tested, and consistently successful. As you imagine a post-60/40 world, this is a group you should learn more about.

Fund website

Long Short Advisors. The site remains pretty Spartan. Happily, the advisor is quite approachable so it’s easy to get information to help complete your due diligence.

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2016. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact us.