By Editor

At the time of publication, this fund was named RiverPark/Wedgewood.

Objective

Wedgewood pursues long-term capital growth, but does so with an intelligent concern for short-term loss. The manager invests in 20-25 predominately large-cap market leaders. In general, that means recognizable blue chip names (the top four, as of 08/11, are Google, Apple, Visa, and Berkshire Hathaway) with a market value of more than $5 billion. They describe themselves as “contrarian growth investors.” That translates to two principles: (1) target great businesses with sustainable, long-term advantages and (2) buy them when normal growth investors – often momentum-oriented managers – are panicking and running away. They then tend to hold stocks for substantially longer than do most growth managers. The combination of a wide economic moat and a purchase at a reasonable price gives the fund an unusual amount of downside protection, considering that it remains almost always fully-invested.

Adviser

RiverPark Advisors, LLC. Executives from Baron Asset Management, including president Morty Schaja, formed RiverPark in July 2009. RiverPark oversees the five RiverPark funds, though other firms manage three of the five. Until recently, they also advised two actively-managed ETFs under the Grail RP banner. A legally separate entity, RiverPark Capital Management, runs separate accounts and partnerships. Collectively, they have $100 million in assets under management, as of August 2011. Wedgewood Partners, Inc. manages $1.1 billion in separate accounts managed similarly to the fund and subadvises the fund and provides the management team and strategy.

Manager

David Rolfe. Mr. Rolfe has managed the fund since its inception, and has managed separate accounts using the same strategy since 1993. He joined Wedgewood that year and was charged with creating the firm’s focused growth strategy. He holds a BA in Finance from the University of Missouri at St. Louis, a durn fine school.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

Mr. Rolfe and his associates clearly believe in eating their own cooking. According to Matt Kelly of RiverPark, “not only has David had an SMA invested in this strategy for years, but he invested in the Fund on day 1”. As of August 1, David and his immediate family’s stake in the Fund was approximately $400,000. In addition, 50% of Wedgewood’s 401(k) money is invested in the fund. Finally, Mr. Rolfe owns 45% of Wedgewood Partners. “Of course, RiverPark executives are also big believers in the Fund, and currently have about $2 million in the Fund.”

Opening date

September 30, 2010

Minimum investment

$1,000 across the board.

Expense ratio

1.25% on assets, in the retail version of the fund, of $29 million (as of August 2023). The institutional shares are 1.00%. Both share classes have a waiver on the expense ratio.

Comments

Americans are a fidgety bunch, and always have been. Alexis de Tocqueville observed, in 1835 no less, that our relentless desire to move around and do new things ended only at our deaths.

A native of the United States clings to this world’s goods as if he were certain never to die; and he is so hasty in grasping at all within his reach that one would suppose he was constantly afraid of not living long enough to enjoy them. He clutches everything, he holds nothing fast, but soon loosens his grasp to pursue fresh gratifications.

Our national mantra seems to be “don’t just sit there, do something!”

That impulse affects individual and professional investors alike. It manifests itself in the desire to buy into every neat story they hear, which leads to sprawling portfolios of stocks and funds each of which earns the title, “it seemed like a good idea at the time.” And it leads investors to buy and sell incessantly. We become stock collectors and traders, rather than business owners.

Large-cap funds, and especially large large-cap funds, suffer similarly. On average, actively-manage large growth funds hold 70 stocks and turn over 100% per year. The ten largest such funds hold 311 stocks on average and turn over 38% per year

The well-read folks at Wedgewood see it differently. Manager David Rolfe endorses Charles Ellis’s classic essay, “The Losers Game” (Financial Analysts Journal, July 1975). Reasoning from war and sports to investing, Ellis argues that losers games are those where, as in amateur tennis,

The amateur duffer seldom beats his opponent, but he beats himself all the time. The victor in this game of tennis gets a higher score than the opponent, but he gets that higher score because his opponent is losing even more points.

Ellis argues that professional investors, in the main, play a losers game by becoming distracted, unfocused and undistinguished. Mr. Rolfe and his associates are determined not to play that game. They position themselves as “contrarian growth investors.” In practical terms, that means:

They force themselves to own fewer stocks than they really want to. After filtering a universe of 500-600 large growth companies, Wedgewood holds only “the top 20 of the 40 stocks we really want to own.” Currently, 63% of the fund’s assets are in its top ten picks.

They buy when other growth managers are selling. Most growth managers are momentum investors, they buy when a stock’s price is rising. If the company behind the stock meets the firm’s quantitative (“return on equity > 25%”) and qualitative (“a dominant product or service that is practically irreplaceable or lacks substitutes”) screens, Wedgewood would rather buy during panic than during euphoria.

They hold far longer once they buy. The historical average for Wedgewood’s separate accounts which use this exact discipline is 15-20% turnover where, as I note, their peers sit around 100%.

And then they spend a lot of time watching those stocks. “Thinking and acting like business owners reduces our interest to those few businesses which are superior,” Rolfe writes, and he maintains a thoughtful vigil over those businesses. For folks interested in looking over their managers’ shoulders, Wedgewood has posted a series of thoughtful analyses of Apple. Mr. Rolfe had a new analysis out to his investors within a few hours of the announcement of Steve Jobs’ resignation:

Mr. Jobs is irreplaceable. That said. . . [i]n the history of Apple, the company has never before had the depth, breadth, scale and scope of management, technological innovation and design, financial resources and market share strength as it possesses today. Apple’s stock will take its inevitable lumps over the near-term. If the Street’s reaction is too extreme we will buy more. (With our expectation of earnings power of +$40 per share in F2012, plus $100 billion in balance sheet liquidity by year-end 2011, the stock is an extreme bargain – even before today’s news.)

Beyond individual stock selection, Mr. Rolfe understood that you can’t beat an index with a portfolio that mirrors an index and so, “we believe that our portfolios must be constructed as different from an index as possible.” And they are strikingly different. Of 11 industry sectors that Morningstar benchmarks, Wedgewood has zero exposure to six. In four sectors, they are “overweight” or “underweight” by margins of 2:1 up to 7:1. Technology is the only near normal weighting in the current portfolio. The fund’s market cap is 40% larger than its benchmark and its average stock is far faster growing.

None of which would matter if the results weren’t great. Fortunately, they are.

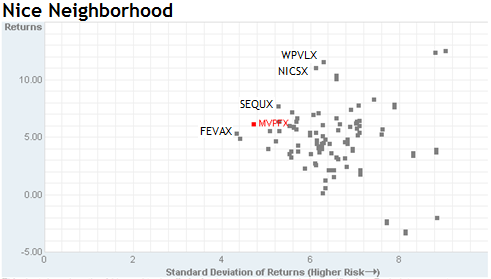

Returns are high. From inception (9/92) to the end of the most recent quarter (6/11), Wedgewood’s large growth accounts returned 11.5% annually while the Russell 1000 Growth index returned 7.4%. Wedgewood substantially leads the index in every trailing period (3, 5, 7, 10 and 15 years). It also has the highest alpha (a measure of risk-adjusted performance) over the past 15 years of any of the large-cap growth managers in its peer group.

Risk is moderate and well-rewarded. Over the past 15 years, Wedgewood has captured about 85% of the large-cap universe’s downside and 140% of its upside. That is, they make 40% more in a rising market and lose 15% less in a falling market than their peers do. The comparison with large cap mutual funds is striking. Large growth funds as a whole capture 110% of the downside and 106% of the upside. That is, Wedgewood falls far less in falling markets and rises much more in rising ones, than did the average large-growth fund over the past 15 years.

Statisticians attempt to standardize those returns by calculating various ratios. The famous Sharpe ratio (for which William Sharpe won a Nobel Prize) tries to determine whether a portfolio’s returns are due to smart investment decisions or a result of excess risk. Wedgewood has the 10th highest Sharpe ratio among the 112 managers in its peer group. The “information ratio” attempts to measure the consistency with which a manager’s returns exceeds the risks s/he takes. The higher the IR, the more consistent a manager is and Wedgewood has the highest information ratio of any of the 112 managers in its universe.

The portfolio is well-positioned. According to a Morningstar analysis provided by the manager, the companies in Wedgewood Growth’s portfolio are growing earnings 50% faster than those in the S&P500, while selling at an 11% discount to it. That disconnect serves as part of the “margin of safety” that Mr. Rolfe attempts to build into the fund.

Is there reason for caution? Sure. Two come to mind. The first concern is that these results were generated by the firm’s focused large-growth separate accounts, not by a mutual fund. The dynamics of those accounts are different (different fee structure and you might have only a dozen investors to reason with, as opposed to thousands of shareholders) and some managers have been challenged to translate their success from one realm to the other. I brought the question to Mr. Rolfe, who makes two points. First, the investment disciplines are identical, which is what persuaded the SEC to allow Wedgewood to include the separate account track record in the fund’s prospectus. For the purpose of that track record, the fund is now figured-in as one of the firm’s separate accounts. Second, internal data shows good tracking consistency between the fund and the separate account composite. That is, the fund is acting pretty much the way the separate accounts act.

The other concern is Mr. Rolfe’s individual importance to the fund. He’s the sole manager in a relatively small operation. While he’s a young man (not yet 50) and passionate about his work, a lot of the fund’s success will ride on his shoulders. That said, Mr. Rolfe is significantly supported by a small but cohesive and experienced investment management team. The three other investment professionals are Tony Guerrerio (since 1992), Dana Webb (since 2002) and Michael Quigley (since 2005).

Bottom Line

RiverPark Wedgewood is off to an excellent start. It has one of the best records so far in 2011 (top 6%, as of 8/25/11) as well as one of the best records during the summer market turmoil (top 3% in the preceding three months). Mr. Rolfe writes, “We are different. We are unique in that we think and act unlike the vast majority of active managers. Our results speak to our process.” Because those results, earned through 18 years of separate account management, are not well known, advisors may be slow to notice the fund’s strength. RWGFX is a worthy addition to the RiverPark family and to any stock-fund investors’ due-diligence list.

Fund website

Wedgewood Fund

Ellis’s “Losers Game” offers good advice for folks determined to try to beat a passive scheme, much of which is embodied here. I don’t know how long the article will remain posted there, but it’s well-worth reading.

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2011. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact [email protected].

(Editor’s note: Glickstein worked for a decade as a reporter and editor on daily newspapers, and he won a National Press Club award for consumer journalism. He dipped his toes into politics as a campaign press secretary for the late Washington Gov. Booth Gardner. He later worked for nearly three decades in communications for what was then the nation’s largest consumer healthcare cooperative, now part of Kaiser Permanente. While there, he served as an intranet webmaster reaching 10,000 employees. His book, After Yorktown, was named one of the 100 best books ever written about the Revolution by the Journal of the American Revolution.) Continue reading →

(Editor’s note: Glickstein worked for a decade as a reporter and editor on daily newspapers, and he won a National Press Club award for consumer journalism. He dipped his toes into politics as a campaign press secretary for the late Washington Gov. Booth Gardner. He later worked for nearly three decades in communications for what was then the nation’s largest consumer healthcare cooperative, now part of Kaiser Permanente. While there, he served as an intranet webmaster reaching 10,000 employees. His book, After Yorktown, was named one of the 100 best books ever written about the Revolution by the Journal of the American Revolution.) Continue reading →

The Cook and Bynum Fund

The Cook and Bynum Fund