Originally published in July 1, 2013 Commentary

In Andy Kessler’s book “Running Money,” he describes the following conversation with an interested investor just after his fledgling Velocity Capital hedge fund starts to attract some healthy attention:

“What percentage of your fund is short?”

“None,” I answered.

“You guys don’t short?” he asked almost incredulously.

“No. We never have.”

“But why not?” he asked.

We had been asked this question a million times.

“Well, there is an unlimited potential for loss.” This means that if the stock keeps going up, you have to buy it back at much higher prices. Imagine shorting Microsoft in 1986.

“And any gains are short-term gains taxed at twice the rate as long-term capital gains,” I added.

“OK, fair enough, but…”

“And you can only make 100.”

“Excuse me?” he asked. It was a flippant answer but the only real one.

“Sure. We like to spend our time finding things that go up by 5 times or 10 times. If we spend our time finding shorts, the most you can make is 100 and only if the stock goes to zero.”

“So you’re not hedged?” he asked.

“We think our hedge is to avoid the losers,” I said.

Mr. Kessler was in search of the “ten bagger,” a term coined by Peter Lynch, famed Fidelity Magellan PM from 1977-90. It represents a ten-fold increase in stock return. In baseball talk, it is the number of bases passed (aka “bagged”) while playing the game, or in this case, the equivalent of two home runs and a double.

Here is retired Mr. Lynch during a PBS interview describing how the “ten bagger” should play into an investor’s strategy:

“You don’t need a lot in your lifetime. You only need a few good stocks. I mean how many times do you need a stock to go up ten-fold to make a lot of money? Not a lot. You made ten times your money.”

“I think the secret is if you have a lot of stocks, some will do mediocre, some will do okay, and if one or two of ’em go up big time, you produce a fabulous result.”

“Some stocks go up 20-30 percent and they get rid of it and they hold onto the dogs. And it’s sort of like watering the weeds and cutting out the flowers. You want to let the winners run.”

“So that’s been my philosophy. You have to let the big ones make up for your mistakes. In this business if you’re good, you’re right six times out of ten. You’re never going to be right nine times out of ten.”

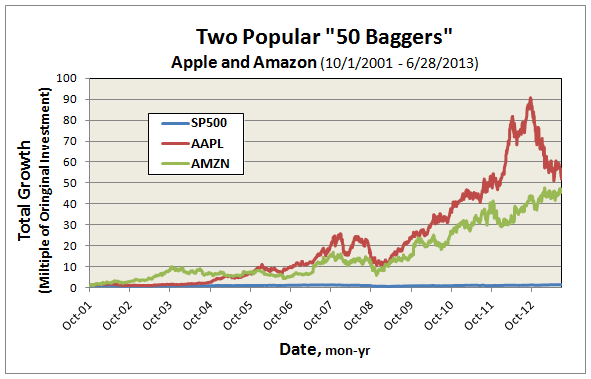

Here are a couple recent examples we should all be familiar with: An investment in Apple AAPL or Amazon AMZN on October 1, 2001, less than 12 years ago, has produced returns of 40% annually. Each has multiplied original investment about 50 times, or 12 home runs and a double. What does a 50 bagger look like? Here, in comparison with SP500:

Can you imagine shorting Apple? Well, actually, DoubleLine bond wizard Jeffrey Gundlach called for shorting Apple last year before it hit a high of $705. It’s now trading about $400, producing a handsome 40% return, even after margin costs and short fees.

Still, in Lynch’s baseball parlance, it’s not even a single.

Selling short goes against market trend, which over time, is definitely up. But Seth Klarman warns the situation is worse than that – the market, he describes in his book “Margin of Safety,” has a bullish bias:

Investors must never forget that Wall Street has a strong bullish bias, which coincides with its self-interest. Wall Street firms can complete more security underwritings in good markets than in bad. Brokers, likewise, do more business and have happier customers in a rising market.

Wall Street research is strongly oriented toward buy rather than sell recommendations, for example. Perhaps this is the case because anyone with money is a candidate to buy a stock or bond, while only those who own are candidates to sell.

Others share Wall Street’s bullish bias. Investors naturally prefer rising security prices to falling ones, profits to losses. Companies too prefer to see their own shares rise in price.

Even government regulators of the securities markets have a stake in the markets’ bullish bias. The combination of restrictive short-sale rules and the limited number of investors who are both willing and able to accept the unlimited downside risk of short-selling increases the likelihood that security prices may become overvalued.

The Dow Jones-Irwin Guide To Common Stocks puts it this way: “…stocks should not be shorted unhedged against a generally upward market trend unless one is extremely confident that a price decline is imminent.” The same guide also relays how individual company performance (ie., earnings, dividends) is lower on information hierarchy in determining stock price movement than overall market or industry subgroup factors.

In short-selling, investors must pay when companies issue a dividend. There is also the hazard of an under-performing company getting acquired, which tends to make stock price soar. Finally, there’s danger in the “short-squeeze,” where large traders appear to prop-up a stock, causing short-sellers to cover and making the stock price ascend even more.

Famed Yale endowment manager David Swensen summarizes the case for disciplined long/short investing as follows:

Long/short equity managers must consistently produce better than top-quartile returns to justify the fee structure accepted by hedge fund investors. Unfortunately, the resources required to identify and engage high-quality investment managers far exceed the resources available to the typical individual investor. The high degree of dependence on active management and the expensive nature of fee arrangements combine to argue against incorporating long/short investment strategies in most investor portfolios.

But what about “The Greatest Trade Ever”? Gregory Zuckerman’s book detailing how John Paulson’s short-selling of subprime mortgages in 2007 made billions, turning Paulson & Co. into one of biggest hedge funds ever. Andrew Redleaf also successfully predicted the financial crisis and his attendant short-sales earned a handsome gain for Whitebox investors – “A Hedge Fund That Saw What Was Coming,” wrote the NY Times. And, of course, in 1992 Stanley Druckenmiller and Geroge Soros bet against the British pound, earning a fortune for Quantum Fund and a reputation for breaking the Bank of England.

Placing a successful short it seems is perhaps more akin to the Great Bambino calling his shot in the 1932 World Series – you know…the stuff of legends.

Charles/30June13