Dear friends,

Another school year has begun, likely the most fascinating in my 35 years as a college professor. My students were in class this morning, cheerful and masked. When asked about their summers, they did not say what the rest of us might: “it sucked.” To the contrary, they were uniformly positive about the experience (“I had a good summer! We didn’t get to travel anywhere, but I put in a lot of hours on my job and spent a bunch of time with my family!”) and hopeful for the year ahead.

The number of students was, quite understandably, reduced: Augustana welcomed something like 550 first-years when we’d normally see 700, with a lot of the deficit coming from international students – well more than a tenth of the college – not able (or willing) to travel to the US this fall. Most have deferred admission until spring, and they’ll bring a lot of energy and perspective at a time of year when everything normally feels set and settled.

Day One began with two hours of introduction to propaganda, one of my academic specialties; I’ve been teaching “Propaganda in the Twentieth Century” for nearly 30 years now, though publishing only lightly in the area. The recurrent themes in the history of propaganda – fostering fear, playing on emotions, dividing people – have been on my mind as I’ve written this month’s missive. I hope you find it interesting.

The Eve of Destruction

Yeah, my blood’s so mad, feels like coagulatin’

I’m sittin’ here just contemplatin’

I can’t twist the truth, it knows no regulation

Handful of Senators don’t pass legislation

And marches alone can’t bring integration

When human respect is disintegratin’

This whole crazy world is just too frustratin’

And you tell me over and over and over again my friend

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction

Think of all the hate there is in Red China

Then take a look around to Selma, Alabama

Ah, you may leave here for four days in space

But when you return it’s the same old place

The poundin’ of the drums, the pride and disgrace

You can bury your dead but don’t leave a trace

Hate your next door neighbor but don’t forget to say grace

And you tell me over and over and over and over again my friend

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction

If you can get past the … hmmm, occasionally strained lyrics, the song feels curiously contemporary: a gridlocked Senate, protests over racism, rising conflict with China, married to a sense that we’d lost all tolerance of – much less respect for – one another.

Given that, you can hear the incredulity in the refrain: “you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction?” (You fool!)

The Byrds rejected the song but the Turtles (whose entire m.o. was to record songs that weren’t quite good enough for The Byrds to do) released it. The most famous version was, you might recall, Barry Maquire’s. July 1965. Raspy voice channeling fear and outrage. The song made it to #1 on the Billboard charts despite being banned by some radio stations (and all of Scotland), restricted by the BBC, and condemned by those who felt criticized. After he became a born-again Christian, Barry re-recorded the song for his album “Lighten Up” and has periodically rewritten and performed the song. Most recently, in 2008.

The Byrds rejected the song but the Turtles (whose entire m.o. was to record songs that weren’t quite good enough for The Byrds to do) released it. The most famous version was, you might recall, Barry Maquire’s. July 1965. Raspy voice channeling fear and outrage. The song made it to #1 on the Billboard charts despite being banned by some radio stations (and all of Scotland), restricted by the BBC, and condemned by those who felt criticized. After he became a born-again Christian, Barry re-recorded the song for his album “Lighten Up” and has periodically rewritten and performed the song. Most recently, in 2008.

Sang it, but he didn’t write it. That credit goes to P. F. “Flip” Sloan, who also penned “Secret Agent Man.”

This whole crazy world is just too frustratin’.

We are, I suspect, always on the eve of destruction. And yet, somehow, we keep dodging the day of destruction.

Why is that? It might be that “destruction” is being oversold. Propagandists know that we’re easiest to control when we’re almost paralyzed with fear: when it feels like everything is spinning out of control, “all that is solid melts into air,” and that we are surrounded by threats, traitors, and enemies. And so they work hard to create precisely that sense: scenes are staged, hyped, ripped out of context, misinterpreted, tweeted, and relentlessly retweeted. Because keeping the details straight is, frankly, exhausting, most of us eventually just surrender to the propaganda and pseudo-events.

Too, it might be that we’re a bit more resilient than we think. A bit more able to step back, think it through, talk carefully, act well.

All of which we mention because the next eight weeks we’ll be deluged by hateful messages, most containing the barest grain of truth, that aim to make us rage. They’re hard to avoid, in part because they flood our environment, in part because they’re designed to be eye-catching, and, in part, because we’re drawn to them in the same way that we’re drawn to stare at the car wreck as we drive by.

Our world faces profound challenges, and the election of 2020 is going to be incredibly consequential. That’s pretty much a given. The question is, how do you navigate the months ahead so that you can make a positive difference in the world without losing your sanity and surrendering to the hate being offered up to you?

Voting would be one good move. Avoiding the propagandists would be another: ad spending – online and on TV – is apt to exceed $6 billion, and almost all of it will be negative (because negative works). You really might want to throttle back on your time spent staring at screens and the worst offenders will be your favorite sites and stations because propagandists know who you are and where you hang out. Unless you’re undecided about your vote in the upcoming election – a bit under 10% of us – more media is going to mean more anxiety. On whole, it is probably not good for you to rage-watch, rage-scroll, rage-tweet … or, well, rage.

We’ve taken to Netflix lately, watching some fascinating Asian shows, including “The Midnight Diner” (set in Toyk0) and “The Mystic Pop-Up Bar” (Seoul). They’re really interesting. Books are a good idea. Actually talking with people has its antique charms.

And if you are one of The Undecided Tenth? Perhaps talking with someone who doesn’t necessarily agree with you but who’s also trying to figure it out, would help you both.

Perhaps, given a bit less pressure and a bit more thought, we can again push the eve of destruction back to another day.

There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so. (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2)

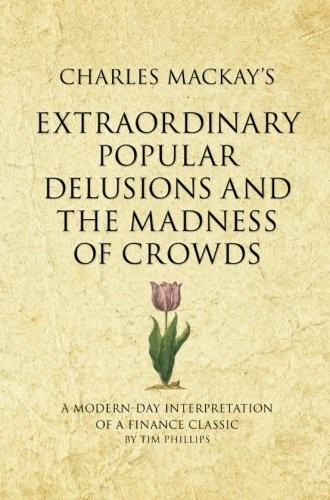

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

A fascinating book, written in 1841 Scotsman Charles Mackay. Never at a loss for words, Mackay wrote three volumes, the first of which was entitled “National Delusions.” The book opens with a series of case studies of economic manias (the South Sea Company bubble of 1711-20, the French land speculation frenzy known as the Mississippi Bubble, and the Dutch tulip mania. “Money,” he notes in the Preface, “has often been a cause of the delusion of multitudes. Sober nations have all at once become desperate gamblers, and risked almost their existence upon the turn of a piece of paper.” (In reality, Mackay was very hesitant to let facts get in the way of a good story and historians have long known that he seriously overhyped the tulip mania because it suited his ends.)

A fascinating book, written in 1841 Scotsman Charles Mackay. Never at a loss for words, Mackay wrote three volumes, the first of which was entitled “National Delusions.” The book opens with a series of case studies of economic manias (the South Sea Company bubble of 1711-20, the French land speculation frenzy known as the Mississippi Bubble, and the Dutch tulip mania. “Money,” he notes in the Preface, “has often been a cause of the delusion of multitudes. Sober nations have all at once become desperate gamblers, and risked almost their existence upon the turn of a piece of paper.” (In reality, Mackay was very hesitant to let facts get in the way of a good story and historians have long known that he seriously overhyped the tulip mania because it suited his ends.)

John Waggoner has been writing – rather more gracefully and I, truth be told – about markets and investing for more than 30 years, most recently as a contributor to Kiplinger’s, Morningstar, USA Today and InvestmentNews. He suggests that MacKay also recognized the herd-like (lemming-like) behavior that’s behind much bad investing, and bad journalism:

“What a shocking bad hat!’ was the phrase that was next in vogue. No sooner had it become universal, than thousands of idle but sharp eyes were on the watch for the passenger whose hat shewed any signs, however slight, of ancient service. Immediately the cry arose, and, like the war-whoop of the Indians, was repeated by a hundred discordant throats. He was a wise man who, finding himself under these circumstances ‘the observed of all observers,’ bore his honours meekly.

Mackay came to mind again as I read two reports this month. Number One: amateur investors are yet again flocking to the markets. The most famous platform is Robinhood, with a reported 13,000,000 users but they’re not alone.

In China, regular people are packing into brokerage houses to buy shares. Americans are feverishly refreshing their Robinhood and TD Ameritrade brokerage apps, while newbie traders in India are enamored with penny stocks. A growing number of Brits, too, are taking a fancy to shares. Quartz, 8/31/2020

The Wall Street Journal (8/31/2020) reports that “individuals account for a greater chunk of market activity than at any time during the past 10 years” and that Asian exchanges, in particular, are dominated by individual traders (Alexander Osipovich, “Individual-Investor Boom Reshapes U.S. Stock Market”). One source “drew parallels with the dot-com boom in the 1990s.”

Number Two: new investors are embracing risky behaviors. In part, their behavior is being shaped by an intentional, designed, series of technologically-mediated “nudges” that encourages risk-taking.

But at least part of Robinhood’s success appears to have been built on a Silicon Valley playbook of behavioral nudges and push notifications, which has drawn inexperienced investors into the riskiest trading, according to an analysis of industry data and legal filings, as well as interviews with nine current and former Robinhood employees and more than a dozen customers. And the more that customers engaged in such behavior, the better it was for the company, the data shows.

More than at any other retail brokerage firm, Robinhood’s users trade the riskiest products and at the fastest pace, according to an analysis of new filings from nine brokerage firms by the research firm Alphacution for The New York Times.

In the first three months of 2020, Robinhood users traded nine times as many shares as E-Trade customers and 40 times as many shares as Charles Schwab customers, per dollar in the average customer account in the most recent quarter. They also bought and sold 88 times as many risky options contracts as Schwab customers, relative to the average account size, according to the analysis. (“Robinhood Has Lured Young Traders, Sometimes With Devastating Results” New York Times, 7/8/2020)

They are trading at eight to 40 times the rate of more experienced investors? An ETrade survey of hundreds of young (ages 18-34) investors found that they’re much more concerned about how much they can make rather than how much they can lose. ETrade reports that for younger investors:

- Risk tolerance skyrockets since the pandemic. Over half (51%) of Gen Z and Millennial investors say their risk tolerance has increased since the coronavirus outbreak, 23 percentage points higher than the total population.

- They are taking cash off the sidelines. Over one in three investors (34%) under the age of 34 said they are moving out of cash and into new positions, 15 percentage points higher than the total population.

- And they are trading more frequently. Over half of investors (51%) under the age of 34 said they are trading equities and 46% said they’re trading derivatives more frequently since the pandemic, compared to 30% and 22% of the total population, respectively.

- They’re optimistic about a quick recovery. While only 9% of young investors said their investment portfolios have recovered since the beginning of the pandemic, 50% think it will happen in the next six months, compared to 33% of the total population.

- Health concerns come first, but portfolio concerns are a close second. Personal health (58%) and investment portfolio (53%) concerns remain the top worries for young investors in the wake of the pandemic.

“The effect [of the pandemic] on the US and global economies” was way down on their list.

Mohamed el-Erian, once PIMCO’s CIO, concludes,

It is hard to overstate the extent of today’s risk-taking in US financial markets. Yes, it would take a big shock for markets to move significantly lower — such as a renewed sharp economic downturn, a considerable monetary or fiscal policy mistake, or market defaults and liquidity accidents. But should such a move occur, the likelihood of further market turmoil would be high, especially given the current lack of a short base to buffer the downturn. This exposes small retail investors to big potential losses. (“Retail stock market investors should note professionals’ caution,” Financial Times, 8/31/2020)

Partly in response, a number of these numbers articles focus on absolute-value and long-short hedging options, ways to buffer your worst-case outcomes without abandoning the stock market.

The Strength of the Weak

The US dollar shows signs of weakening, in part because of the titanic budget deficit; $2.8 trillion so far in fiscal 2020, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The term “weak dollar” is misleading, in part because we immediately associate the words “weak” and “bad.” As in, “a weak dollar is bad.”

The US dollar shows signs of weakening, in part because of the titanic budget deficit; $2.8 trillion so far in fiscal 2020, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The term “weak dollar” is misleading, in part because we immediately associate the words “weak” and “bad.” As in, “a weak dollar is bad.”

Not necessarily. A weak dollar is a description we use when other currencies rise in value with respect to ours. If we’re used to seeing ₤1 being worth $1.34 and suddenly it’s worth $1.50, we decry “a weak dollar.” But if you make a $1 gizmo in the US, the weak dollar means it’s automatically more affordable – hence, more attractive – to British consumers. And if you have invested in a British company, every ₤1 earned by that company suddenly returns more to you in dollars than ever before.

Morningstar suggests (8/18/2020) that investors think about international funds that do not hedge their currency exposure. Fortune adds gold: “when the dollar is down, gold, foreign developed, and emerging-market stocks tend to perform admirably” (“A weakening U.S. dollar makes these 3 assets more attractive for your portfolio,” 8/5/2020). Evie Liu, writing at Barron’s, considers both the obvious candidates such as international equity funds and the investments that would rise in value if a weaker dollar were accompanied by rising prices (something the Fed would love to see). Her watch-list includes unhedged international equities in both developed and developing markets, gold, and community, maybe TIPs and foreign bond ETFs (“It’s Time to Prepare for a Weaker Dollar,” 8/21/2020).

Those preferences seem reflected in Research Affiliates’ latest 10-year asset class projections.

The Masked Ball

Face masks have become (blessedly, since they’re about the best protection we’ve got, see “Face Masks Really Do Matter. The Scientific Evidence Is Growing,” Wall Street Journal, 8/13/2020) the fashion accessory du jour. Because of our responsibilities as college administrators and faculty, Chip and I have had occasion to order masks from more than a dozen different manufacturers. For what perspective it offers, here’s a bit of quick reflection.

Face masks have become (blessedly, since they’re about the best protection we’ve got, see “Face Masks Really Do Matter. The Scientific Evidence Is Growing,” Wall Street Journal, 8/13/2020) the fashion accessory du jour. Because of our responsibilities as college administrators and faculty, Chip and I have had occasion to order masks from more than a dozen different manufacturers. For what perspective it offers, here’s a bit of quick reflection.

- Disposable masks are actually a decent option: they tend to be cooler than cloth masks, reasonably efficient at their primary job, reasonably cheap (we just bought 200 online for $40), and aesthetically inoffensive. They do create a regrettable amount of plastic waste.

- Size matters, especially if your headwear tends to be L to XL. Bunches of “one size fits most” masks are a misery, which includes many of the mass-produced masks from Hanes and Fruit of the Loom. Take the opportunity to look for sized masks.

- Function matters, which means you need to figure out what you’re going to be doing. We found that several masks that are great for wearing out for errands are incredibly hard to teach in. Proper Cloth masks, which are stylish and comfortable with behind-the-head straps, tend to adhere to your mouth when speaking.

- Don’t obsess about the exact fabric composition: cotton, silk, poly, modal, 3D printed … Stick with sensible, general rules of thumb. Hold it up to the light; if you can see, say, your fingers through it, it’s probably too thin. Put a drop of water on the outside of it; if the water soaks in immediately, it’s probably not so protective.

- Generally, more layers are more effective but can get awfully warm, awfully fast.

- Masks are probably best if hand-washed. The more you wash them, the thinner and less protective the fabric gets. And frequently the elastic ear loops get twisted beyond recognition. Regardless of hand- or machine-washing, don’t use fabric softener. It contains wax which makes the mask ineffective.

- Outdoor Research has a comfortable mask ($20) with an anti-viral coating designed to last for 30 washes. They can’t make the anti-viral claim in the US, though apparently its efficacy is recognized by European health authorities.

- Comfortable masks are available through Vista Print and Etsy. Vista Print, which I associate with business cards, makes comfortable masks in a huge variety of patterns. Through the summer, our go-to mask has been a comfortable two-layer cotton mask from DAVEGO at Etsy.

- For modestly-sized heads and modestly risked environments, Shon Simon – a contract clothing manufacturer – makes inexpensive masks in dozens of colors (including six iterations of “nude”) and in packages of one to 500.

- Personalized selfie masks are gross and disturbing, avoid them. Those are the ones with your face printed on them. Ick.

There will continue to be a scientific study a week on mask design. Feel free to ignore most of them and stick to first principles. At base, the best mask is the one that you will wear consistently and properly. (“Properly” means “if air goes it in, make sure it’s covered.”) They will, with time and practice, become no more intrusive than seatbelts – now used by 91% of us, though once loathed and rebelled against – are.

Thanks!

Most especially to the folks at Queens Road for the peanuts!

Love those things.

To the folks at S&F, Wilson, Quang, Michael from Dryden, and Leah for their generous – and, in some cases, generously repeated, support.

And, as ever, to the Faithful Few who contribute monthly: William and William, Matthew, Brian, David, Doug, and Gregory!