“Dogs look up to you, cats look down on you. Give me a pig. He just looks you in the eye and treats you as an equal.”

Winston S. Churchill

I thought I might follow David’s call for a high summer issue that offers our readers “a bit of a breather.” After due consideration, I decided to write a bit about candy and common sense, wine and changing tastes, and the struggle of value investors to deal with changing tastes, changing markets and the Fab Four Five!

Taste Matters

In 2018, Nestlé exited their North American confectionery business. Some twenty well-known brands, such as Baby Ruth, Butterfinger, Crunch, and Raisinets, were purchased by Ferrara Candy, a subsidiary of Ferraro Group, an Italian company that is privately held (and thus not subject to earnings pressures from impatient shareholders). For some years Nestlé had under-invested in the brands, choosing to focus more on what it called its “nutraceuticals” approach, healthy formulations for healthy eating. This approach drove both an acquisition policy as well as reformulations of product lines. Unfortunately, this didn’t always result in products that would appeal to consumers in terms of taste. With Nestlé’s eye on healthy eating, they lost focus on what drove consumer interest in candy (and whether this was by design or neglect I will leave to some historian down the road to figure out).

Ferrara has taken a somewhat different approach. The first brand to receive attention was Crunch, which got an extensive advertising campaign, the first in a decade. The campaign caused what had been flat sales to grow 4%. Butterfinger came next, with a tripling of the advertising budget, a reformulation that used higher quality raw materials, and improved packaging to preserve freshness.

In a recent four-week period, Butterfinger sales were up almost 18%.

I asked a friend who had been one of the better European-based consumer branded food analysts to explain Nestlé’s failure here. She said some of it had to do with a shift in corporate policy goals in terms of what businesses they really wanted to be in. Some of it was a portfolio review, coupled with an acknowledgement of what had been some truly horrendous acquisitions over the years. But most of it had to do with the fact that Ferrara was just a better fit, as a company whose focus was on quality ingredients that produced a product that tasted good and that the consumer liked. Put simply, Ferrara makes things that consumers like because they taste good.

The lesson here is a simple one, especially as many reformulations have taken place in consumer branded food products in recent years. Forget about the laboratory tests and marketing surveys to try and explain why sales are flat to down. Buy the product yourself and take it home to see whether you think it tastes good, and whether your family members think it tastes good. Common sense does work.

Vineyards and Wineries for Sale

An assumption by spirits companies has been that wine consumption will be on an upward sloping growth path for the foreseeable future. Sadly, that is not the case. The Weekend Financial Times in its 27 July/28 July issue made an interesting point when talking about real estate in Napa and Sonoma Counties in California. The Millennials are not that interested in  wine. Citing the Wine Intelligence US Landscapes 2019 report, there are apparently three million fewer wine drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 than there were in 2015. What are they drinking? Mixed drinks and/or artisanal beers. The patience to do tastings to figure out what you like is not there. This will have implications for a number of the spirits companies that still have major wine operations, or those companies that are primarily wine producers. Wine making is a capital-intensive business that has a lot of moving pieces, as well as a number of things that can go wrong before you can actually bring product to market, including disease, weather, failed crops, pestilence, and sometimes, just bad luck. These trends were confirmed in a recent interview in the Weekend Wall Street Journal on July 20-21, 2019 with Rob McMillan, an executive vice president and founder of Silicon Valley Bank’s wine division. He indicated that his survey showed the dominant consumers of fine wine to be the baby boomers, who want to hear about how the wine was produced. And, they want to meet the Wine Whisperer who spoke to the grapes. The Millennials are avoiding wine because of price – it costs more than either beer or spirits. Unless that can change, the wine industry down the way will hit a brick wall.

wine. Citing the Wine Intelligence US Landscapes 2019 report, there are apparently three million fewer wine drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 than there were in 2015. What are they drinking? Mixed drinks and/or artisanal beers. The patience to do tastings to figure out what you like is not there. This will have implications for a number of the spirits companies that still have major wine operations, or those companies that are primarily wine producers. Wine making is a capital-intensive business that has a lot of moving pieces, as well as a number of things that can go wrong before you can actually bring product to market, including disease, weather, failed crops, pestilence, and sometimes, just bad luck. These trends were confirmed in a recent interview in the Weekend Wall Street Journal on July 20-21, 2019 with Rob McMillan, an executive vice president and founder of Silicon Valley Bank’s wine division. He indicated that his survey showed the dominant consumers of fine wine to be the baby boomers, who want to hear about how the wine was produced. And, they want to meet the Wine Whisperer who spoke to the grapes. The Millennials are avoiding wine because of price – it costs more than either beer or spirits. Unless that can change, the wine industry down the way will hit a brick wall.

Where Are All the Value Investors?

I received an email recently from a fund manager who is a value investor. The last several years have been rather daunting for those who call themselves such. In many respects, it brings back memories of the 2000-2001 tech bubble, when value investors were totally out of synch with the markets, and ridiculed big time by both investors and market commentators. In any event, this manager would put himself into the category of being a catalyst-driven value manager, one who focuses on how value will be realized by the shareholder. Events might include asset sales, reinvesting in neglected businesses (a la the Nestlé North American candy brands), new management, shareholder activists rattling the cages. All of these result in event-driven situations causing change. Now what I learned that I had not known was that a number of value shops have shuttered this year. This gentleman was expecting more to follow, especially given the pressures from the shift to passive. He especially felt that the value investment firms who fell into the category of return to the mean investors were most at risk.

Return to the mean as a value strategy can be attractive from a profit-margins of the business point of view. One identifies, usually by various screening methodologies (or just reading the weekly Value Line) those securities that, based on some measure of statistical cheapness, are worthy of further examination. You can make do with a pool of analysts who are relatively inexpensive compared to hiring those with extensive industry experience (those who know when they are being lied to by either managements or the financials vis a vis what the business should produce). Often the hope is that the market at some point identifies your group of below the mean businesses as too cheap. There then is a mad dash to buy them, pushing them all up, in effect a rising tide floating the boats.

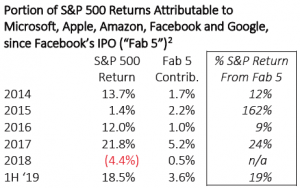

It could happen. But for those with patience, I refer you to Horizon Kinetics’ excellent Q2 Market Commentary. They point out that of the S&P 500’s annualized 10 year return of 14.7% to 6/30/2019, 10% of it came from just five companies – Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. The question they raise is, how much more can the internet grow before saturation is reached and growth rates slow (which means share prices must fall)? The last point I will leave you with, but encourage you to read the entire piece, is that the way indices such as the S&P 500 are constructed leads to them ultimately becoming undiversified. This is because a tiny number of firms become quite successful and dominate their respective index. The under diversification becomes even more of a problem when you account for the misclassification of companies into different industries. After adjustments, they are often very correlated. Indeed, by Horizon’s estimate, the Internet Beneficiary weighting of the S&P 500 is 31.63%.

It could happen. But for those with patience, I refer you to Horizon Kinetics’ excellent Q2 Market Commentary. They point out that of the S&P 500’s annualized 10 year return of 14.7% to 6/30/2019, 10% of it came from just five companies – Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. The question they raise is, how much more can the internet grow before saturation is reached and growth rates slow (which means share prices must fall)? The last point I will leave you with, but encourage you to read the entire piece, is that the way indices such as the S&P 500 are constructed leads to them ultimately becoming undiversified. This is because a tiny number of firms become quite successful and dominate their respective index. The under diversification becomes even more of a problem when you account for the misclassification of companies into different industries. After adjustments, they are often very correlated. Indeed, by Horizon’s estimate, the Internet Beneficiary weighting of the S&P 500 is 31.63%.

So, understand that what you see, or what you think you see, in terms of index diversification, is often not the case. After adjustments, your sector weightings can be quite concentrated. The solution – as said in the past – look for truly uncorrelated businesses. And, try to know what degree of risk you really want to take.