When I came across a quote by Peter Lynch on how passive fund investors were making a mistake, I had two choices: to sweep his comments under the rug or evaluate the validity of them. In the article below, we will look at:

-

- Lynch’s argument

- My researched reasons for preferring passive investing.

- The role of confirmation bias and how it can hurt or help investors.

- The results of a careful analysis of the performance of Mr. Lynch’s preferred funds

- Finally, a few conclusions.

The takeaway: Outperforming MFs do exist but their taxable distributions are a larger drag than expected.

We’re inviting you to join the conversation by completing our first-ever poll: the MFO active/passive preference snapshot, which you’ll find below. We’ll post results after our first week and then again in our May issue.

Peter Lynch Interview

“The move to passive is a mistake,” said Peter Lynch, the legendary one-time manager of Fidelity’s Magellan Fund. According to an article by Tom Moroney and Joe Shortsleeve of Bloomberg Quint from December 7th, 2021, Mr. Lynch also said in a radio interview, “Our active guys have beat the market for 10, 20, 30 years, and I think they’ll keep on doing it.” In reference, he cited three current Fidelity managers: Steve Wymer of the Growth Company fund, Will Danoff of the Contrafund, and Joel Tillinghast of the Low-Priced Stock Fund.

My Investment Portfolio and Aversion to Active Mutual Funds

Upon reading this article, I took a big swallow. A cursory glance at my investment portfolio confirmed what I already knew: I own no actively managed mutual funds.

Having been involved in the market for many decades and also having talked to friends who have invested in stock for far longer, I have formed strong biases. I believe a very limited set of investors have an edge in stock picking, and that these investors tend to work at hedge funds because of the superior compensation payouts. I also have a great degree of difficulty in predicting which MF will do well in the next market cycle because few funds have outperformed in all types of market cycles.

Furthermore, I rationalized my biases by backing them up with market research:

-

- Active MFs have higher fees compared to index funds.

- Active MF performance lags the index over the long term. The SPIVA reports show that 8 out of 10 Equity Mutual Funds underperform the US Equity Index benchmarks when the observation window is stretched out to a 10-year period. For the year 2021, 8 out of 10 actively managed equity funds underperformed the US index.

- Individual fund success does not last. An academic research paper by Prof. James Choi and his graduate student, Kevin Zhao, “Did Mutual Fund Return Persistence Persist?” (2020) finds that “significant performance persistence does not exist in the 1994-2018 period.” Also, this NY Times article for a quick read.

- Poor tax management is common: Annual taxable distributions and dividends by actively managed MF are significant. For those with MF investment assets in taxable brokerage accounts, taxes on distributions are a significant drag on performance. Michael Lane, Head of iShares U.S. Wealth Advisory, reports:

for the 10 years ending in 2019, taxes on distributions reduced returns on the average annual performance of actively managed U.S. Large Cap Blend mutual funds by 1.79 percentage points. Over the same period, the average expense ratio of that category was 0.89%. In other words, while investors are increasingly focused on fund fees – as they should be – the average impact of taxes has been nearly double that of the expense ratio. (“Don’t let taxes drag you down,” BlackRock Advisor Center, 5/26/21)

- Opportunity Cost: While periods of outperformance do not last, periods of serious underperformance are common and last for long. Overlooking this opportunity cost requires a certain level of faith in the investment manager.

(When I read David Snowball’s commentaries of selected funds, I can see his meaningful conversations with certain fund managers have allowed space for his faith to grow. This is perhaps an important reason for active MF managers to make themselves more available.) - Active bond funds didn’t protect in down markets: I owned a lot of active bond managers. Low-interest rates for a decade seduced me to invest with them. Their source of higher carry was mostly driven by credit risk and illiquidity. For some reason, I expected them to skirt an equity market crash. When in March 2020, I saw my bond funds down 15-20%, I was disappointed. I didn’t sell out of those funds into stocks as I was hoping to. Realizing I was the greater fool to expect a free lunch, I eventually exited those active bond funds. (In the 2022 market sell-off, the active bond funds seem to be predictably suffering. There is little outperformance adjusted for the duration.)

- Flow of Funds and the Sage of Omaha’s future widow’s portfolio: The amount of money flowing into passive investing from active over the last ten years must be a few trillion dollars. Warren Buffett has said that when he dies, he would like his widow’s assets to be invested 90% in the S&P 500 Index and 10% in T-Bills. Cumulatively, the high fees and underperformance of most actively managed equity MF have been quite clear for all to see.

None of this is to say that active fund management does not work; only that I could not make it work for me. Others might have a different and more promising story. My aversion to active MF investing makes me a strange bedfellow in the Mutual Fund Observer community. But it also allows me an opportunity to learn from others who have faith.

Confirmation Bias

Peter Lynch’s contradictory comments about my biases and research came unannounced and forced me to think: “What is his incentive to call the passive crowd wrong?” I wondered. “Is this an advisor to Fidelity talking or is there genuine merit in his argument?”

I peered inside my own mind. By ignoring Mr. Lynch’s message and looking only for research that supported my existing bias and thesis, I would be engaging in the behavioral shortfall known as Confirmation Bias.

Here is Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast and Slow, as quoted in an article by Drake Bear in The Cut: “Where does confirmation bias come from? Confirmation bias comes from when you have an interpretation, and you adopt it, and then, top-down, you force everything to fit that interpretation.”

Confirmation Bias makes us seek out like-minded people, who share our opinions, our views on the world, and on investments. Confirmation Bias means I look up and down for facts that will make me feel better about my already established investment thesis. It means overlooking every contradictory fact because it would be inconvenient to my way of thinking. All investors are susceptible to Confirmation Bias because there is a fine line between deeply believing something and questioning that belief by putting it to the test. Most people find it difficult to learn and invest well.

For example, there are believers and non-believers in cryptocurrency. Whichever side one is influenced by, that’s the “correct” side. Every dialogue has the feel of pushing people deeper into their established biases.

Precisely, therefore, in the field of investing, talking to people who see things dramatically differently from us can often bring us the greatest benefit. It can save us from our biases and self-selected group think. To avoid Confirmation Bias, if I am truly bullish on a stock or an investment idea, I find the biggest bear and listen to his/her arguments.

I have learnt that I usually learn from these conversations and temper my bullish or bearish enthusiasm. And on rare occasions, I have strengthened my own convictions and bet bigger, because I know the opposite thesis is weaker.

I will admit that it’s hard to undergo this ego-crushing exercise. It’s far easier to block out the other voice. It is so much more comfortable to just see my version of the world as correct and every other version wrong.

Taking President George W. Bush’s “You are either with us, or against us” may work in geopolitics, but it is a disaster recipe for an investor. Being open-minded is more lucrative.

As inconvenient as it was, I knew that Mr. Lynch was a legend, his words were counter to the music in my own head, and that I ought to go find out if he was correct. I might change my mind and learn something.

The Analysis

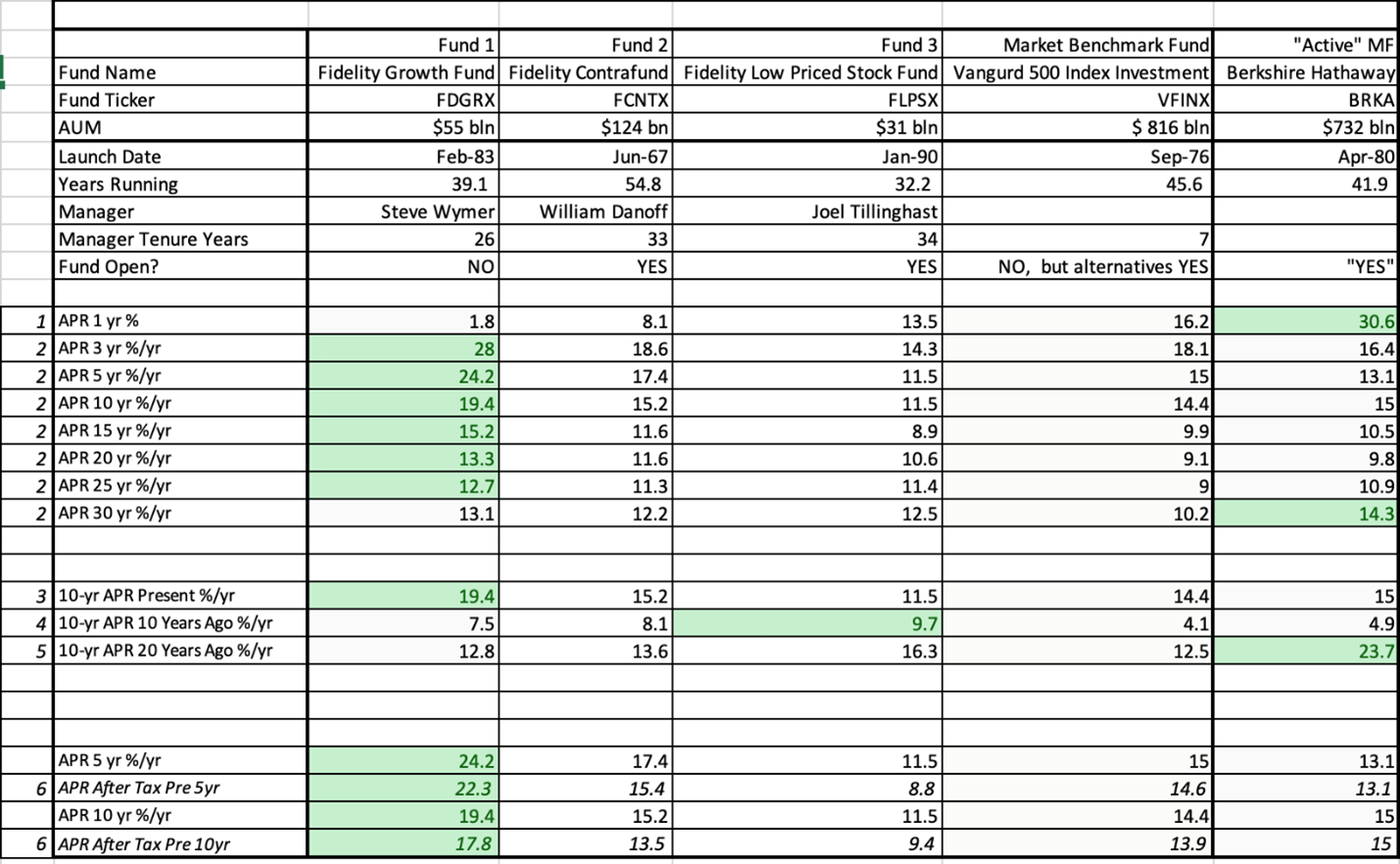

Using the MFO Premium search engine, I analyzed the three aforementioned Fidelity funds. For good measure, I added the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, and also Berkshire Hathaway A shares (my proxy for a well-run actively managed investment). The detailed results table is highlighted at the end of the article along with some technical explanations. Here is a quick analysis:

-

- The Fidelity Growth Company: Mr. Lynch was correct. This fund has absolutely crushed the market benchmark and even Berkshire Hathaway over the last 20-30 years. Unfortunately, the Fund is closed to New Investors as of April 2006.

- The Fidelity Low Stock Fund: This fund did very well in the 90s but NOT since then. It is not one of the funds that have beat the market over the last 10 and 20 years. Mr. Lynch was wrong here.

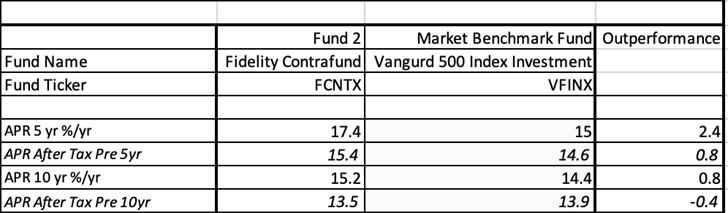

- The Fidelity ContraFund: Mixed results.

-

- The fund is Open and has generally beaten the Market Indices.

- This outperformance has been driven by significant active movement within the portfolio.

- The distributions from the active trading have tax consequences.

- Adjusted for taxes, the fund’s outperformance has disappeared against the market.

- This active fund might work for tax-deferred accounts.

-

- Berkshire Hathaway: Many investors are critical of Warren Buffett for not paying a dividend or distribution. But thanks to NOT paying a distribution, adjusted for taxes, this stock has started outperforming. This, despite the generally noted inability of Berkshire to use its large cash pile for suitable elephant investments.

Conclusion

Have I answered the question I started with on active vs passive? Has the analysis affirmed my existing biases or made me change my opinion about anything?

-

- The Fidelity Growth Company’s massive outperformance is a good wake-up call for me. I learnt that superb and consistent outperformance exists in a Mutual Fund, even in today’s benchmark-driven passive market.

- The Contrafund is interesting because it both outperforms and underperforms the market benchmark fund at the same time. Its outperformance is from Danoff’s investment acumen, and the underperformance from the high taxes on distribution the fund pays. On a related note, Morningstar just downgraded Contrafund (3/22/22) in recognition of the enormous constraints imposed on a manager whose strategy (which covers Contrafund, clones, and related accounts) has grown to $250 billion.

- David Snowball had an interesting take on the Contrafund. Danoff has trained a lot of analysts. How come none of them have performed as well outside of the Contrafund? Maybe Danoff is Betting on the Contrafund means hoping Danoff sticks around.

- I am now open to the idea that there is a select number of fund families (Primecap, Fidelity, Wasatch, Grandeur Peak to name a few) where the investor has a higher shot than the average actively managed mutual fund. I am open to reading and learning more about successful MF managers so I can form faith.

- For most of my investment assets, I still feel comfortable in the warm blanket of passively managed index funds. Only after I have substantial faith in a fund management team would I consider moving my assets, and I would be in no rush to do this.

Remember: join the conversation by completing our quick, easy and anonymous MFO active/passive preference snapshot

For readers who enjoy looking at the detailed data behind my arguments, I’ve reproduced the results of a side-by-side comparison of the short- and long-term performance of Mr. Lynch’s favorite funds. And because taxes sting, I’ve also included their tax-adjusted performance. For each metric, the fund with the single highest performance is flagged with a green box.

Detailed performance record: three Fidelity stars, the S&P 500 and Mr. Buffett

What is APR: It is the Annual Percentage Return of a fund including the Price and Dividend Return, as well as the fees paid.

-

- APR 1yr %: Total fund Return over the last 12 calendar months (March 2021-Feb 2022).

- APR 3yr %/yr.: The total returns are taken for the last 36-months and then recalculated to form an average compounded annual return for the period. This has the effect of averaging the good years with the bad years to give us an approximate number the fund delivered to its investors over the 3-year period. This same calculation is done for the APR 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 in the MFO search engine (or in most financial websites).

- 10-yr APR Present %/yr: The fund’s 10-year total return when annualized on average from Mar-2012 to Feb-2022.

- 10-yr APR 10 Years Ago %/yr: The fund’s 10-year total return when annualized on average from Mar-2002 to Feb-2012.

- 10-yr APR 20 Years Ago %/yr: The fund’s 10-year total return when annualized on average from Mar-1992 to Feb-2002.

- APR After Tax Pre 5yr: The fund’s 5yr APR %/yr is adjusted down to account for the taxable distributions made by the fund. The assumption is the investor is holding the fund in the taxable account and is taxed at the highest marginal ordinary income tax rate at the federal level. No tax is subtracted at the State and Local level.

The After-Tax APR numbers are reported by the funds to the SEC since the early 2000s. This measure was added recently to MFO Premium. Existing fund holders of actively managed mutual funds receive distributions in a tax year when:-

- A fund’s stock holdings pay dividends

- A fund liquidates positions with short-term and long-term capital gains

- Other fund holders exit their fund investment and force the fund to liquidate positions.

-

-

- Fund holders in the Contrafund have been receiving such distributions and it’s been eating into their total returns.