My “Thoughts on Inflation Protection” essay, which appeared in MFO’s February 2022 issue, focused primarily on the role of different major asset classes in providing an inflation buffer for your portfolio. The article was focused in particular on the performance of funds and ETFs with substantial exposure to TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) and similar products. I highlighted the promise of short-duration TIPS funds.

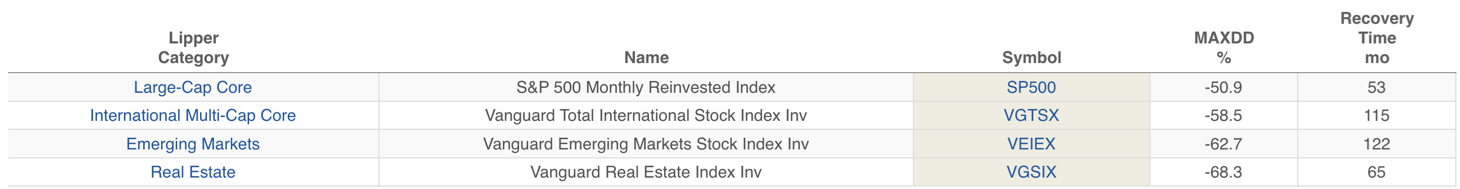

In passing, I also noted the long-term potential role of domestic stocks and Equity REITS in protecting against inflation, while mentioning their two main drawbacks. One, they do not respond well to inflation in the short-term; and two, they act poorly in severe market drawdowns. This past month, Feb 2022, was a timely demonstration of the above reasoning.

I mentioned that “part of an asset’s job is to help protect the portfolio during a financial catastrophe. Risky assets – Equity, REITs, and Stocks – while great for participating in long-term growth, are not good at capital preservation in tough market conditions. To prove the point, I pointed to a one-month drawdown endured by the Vanguard REIT Fund during the Covid-19 pandemic of Feb/March 2020.

A Reader Challenges

That prompted a challenge from a thoughtful reader who has considerable expertise in the fund industry. A lively exchange of views occurred, driven in part by different takes on how long a drawdown must last in order to be of material concern. (Would a 50% decline in your portfolio that lasted two weeks be “better” than a 25% decline that resolved in two months?) That’s a question worth pursuing.

This is a two-part question:

- Easy part: the calculations

- Difficult part: why do the drawdowns matter and for whom?

Part 2 of this question is also a great opportunity to discuss one of the most difficult and imminent problems in investing:

- What is a drawdown?

- How should we define it? How do most investors experience drawdowns? and

- How do successful investors practically and psychologically deal with drawdowns?

Calculating Drawdowns

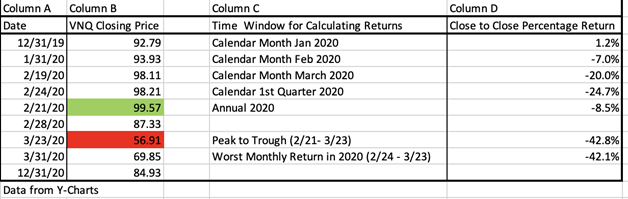

First, let’s look at the calculations. I have picked some dates around the start of the Covid-19 Pandemic as it relates to my comments on Equity REITs in the TIPS article. As a proxy for the Vanguard Real Estate fund, I have chosen the Vanguard Real Estate ETF (VNQ, a fund I own and like).

As we can see from the price history in Column B, 2020 was a very volatile year for VNQ. Starting the year around ~93, the fund rallied in late February ’19 to around $99. Just about 4- weeks later, it crashed and experienced a closing low of ~ $57. The return between those 2 dates is ~ negative 42%. This is the return I had in mind and quoted when I wrote the article.

The reader pointed out, also correctly, that the calendar monthly returns in Feb ’20 and March ’20 were negative 7% and negative 20% respectively. Therefore, claiming that fund had a “1- month” return of negative 42% is incorrect. He pointed out that only a trader, not an investor, would call Peak to Trough using a 4-week intra-month period as a drawdown.

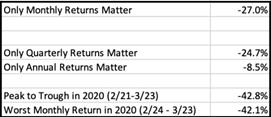

According to Investopedia, a drawdown is a peak-to-trough decline during a specific period for an investment, trading account, or fund. Since each investor has their own definition of a specific period, there can be multiple right answers for defining drawdowns. VNQ’s 2020 drawdowns can be:

Is any of these drawdowns more legitimate than the others? Very quickly, we can divine that the right drawdown answer lies in the eyes of the beholder. When the market moves as much as it did in 2020, a lot of common definitions and reference points we take for granted no longer work. The market is made up of many investors, each of whom may look at the world differently.

Why do drawdowns matter, and for whom?

However, the more interesting question here is why should investors care about drawdown? Why is it important to discuss and learn from the drawdown in Equity REITs in the year 2020? When we ponder this question in-depth, we learn a lot about the process of investing. Let us now spend some time thinking about the more difficult drawdown questions.

In the field of investing, there are two principal regrets:

- when an asset goes up a lot, and we don’t own it

- when an asset goes down a lot, and we do own

The first regret is when we miss buying something that goes on to have a phenomenal rally. “We had a chance to buy Tesla at $30, but we didn’t. We missed buying Tesla!” would fall in this category. This loss is called opportunity loss. Investors think of how much money we could have made if we had pulled the trigger. No uninvested money is actually lost. People remember missed investments perhaps in a similar way to recalling a missed chance of falling in love with someone. There is no way of knowing how it would have worked out for us, but our mind likes to believe it would have been great. The human mind can almost always (eventually) rationalize missed opportunities as the role of destiny in life. Because investment opportunities keep arising, a smart person might perhaps be able to learn from past missed opportunities and act differently in the future.

The second regret investors experience is when they have bought an asset and it goes down a lot in price. Everyone defines what “a lot” means differently. Every investor who has invested long enough has experienced sharp selloffs in their portfolio.

In general, when the price of an asset goes down more than 20-30%, that’s a proper drawdown! Investors in the asset feel it viscerally. It hurts to know that a deliberate decision made to buy XYZ, to own XYZ, has now resulted in a substantial reduction of the money we had once associated with XYZ. This feeling is different than opportunity loss. Drawdown-driven losses have the potential to overtake a person’s entire system. “I could have done this, I should have done that, I would have had this much more money…” are thoughts that fill the mind. Drawdowns can be traumatic and sometimes financially catastrophic. When such a drawdown occurs, investors have three choices. Sell the investment, buy more, or do nothing. Portfolio decisions made during such times are consequential to the long-term financial health of the investor.

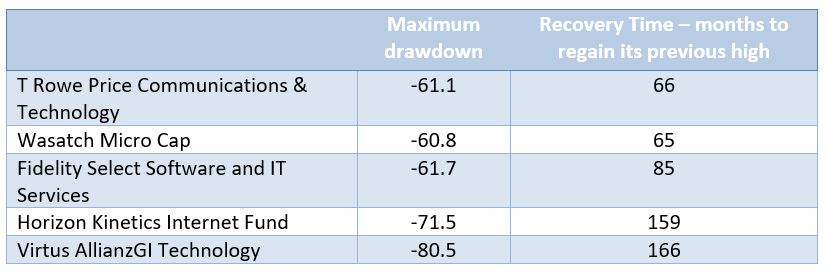

It is far more common for individual stocks to experience large drawdowns than it is for entire major asset classes. Moreover, an individual stock has the potential for bankruptcy. When a stock halves, it is a very difficult moment for an investor. Will the stock be the next Lehman Brothers in 2008 or the next Amazon in 2002? Should the investor buy more, exit the stock, or do nothing. Precisely because security selection is so difficult, many seasoned investors who realize they have not the skill and don’t want to depend on luck, seek returns instead from asset allocation.

How do thoughtful investors structure portfolios to prepare for inevitable drawdowns?

Thoughtful investors choose to own a diversified basket of stocks to prevent the mental panics associated with occasional drawdowns in individual stocks or any one asset class. A major asset class, like the S&P 500 basket of stocks, can halve in price, but will not go bankrupt. In fact, both in 2003 and in 2009, the S&P 500 went down about 50% from peak to trough. Buying/owning the S&P 500 down 50% is a safer bet than buying any one stock down 50 percent.

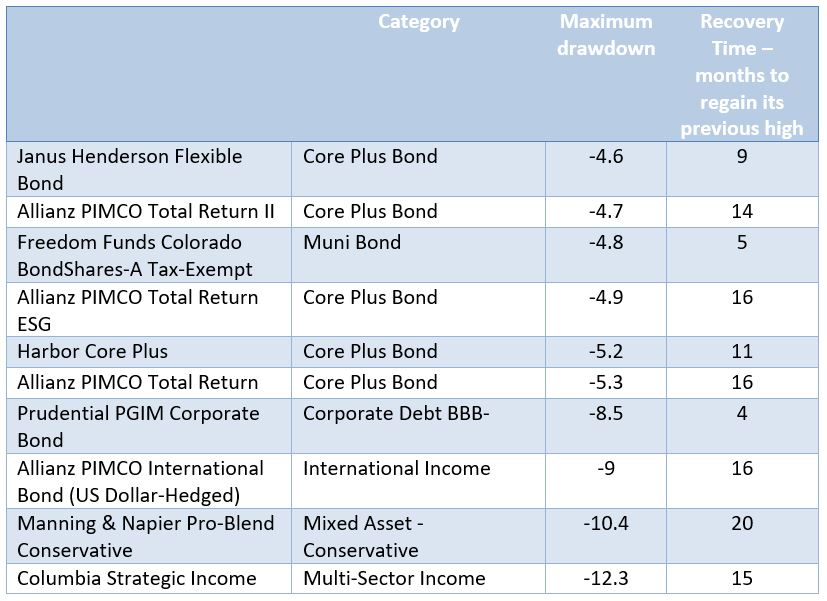

Not only do these investors diversify within an asset class, but they also diversify across asset classes. By owning a combination of Risky and Riskless asset classes, experienced investors anticipate that drawdowns will unexpectedly occur, that not all drawdowns can be predicted in advance, but a system does exist to deal with eventual drawdowns. Having Riskless assets provides a buffer zone in sharp selloffs. By then selling Riskless assets and buying Risky assets, investors can rebalance portfolios: buy low and sell high.

Drawdowns are inevitable and painful for all investors. But using a combination of major asset classes, asset allocation, and portfolio rebalancing, we can harness the same drawdowns and capitalize on them.

A Simple Risky/Riskless Portfolio

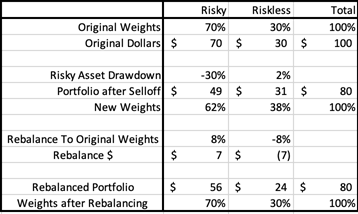

Here is an example of a portfolio with a starting value of $100 split 70/30 between Risky (Stocks) and Riskless assets (short-term T-Bills). In this example, after a 30% drawdown in Risky assets and a 2% increase in Riskless assets, the investor is left with $80. Bad, but not catastrophic. She then decides to Rebalance back to the 70/30 weights. This requires buying the Risky Asset which has suffered the drawdown – the “Buy low” part.

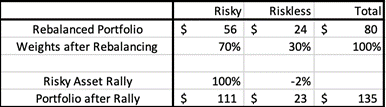

Luckily for her, the drawdown ends, the market turns around, and Risky assets go on to rise 100% in price over the next few years. Riskless assets sell off 2%. How does the portfolio do?

She can rebalance once again here and execute the “Sell High” part.

What if she had not rebalanced the portfolio during the drawdown?

Thus, we see that rebalancing the portfolio added an incremental $7 of value to her portfolio compared to not rebalancing.

Practical Aspects of Rebalancing Portfolios

Drawdowns can be painful, but they can be useful to rebalance. Yet, one must pose the deeper question: how do I know when a meaningful drawdown has occurred and that I should practice rebalancing? It requires looking at the portfolio periodically, calculating percentage weights of asset classes in the portfolio, and executing trades to actually rebalance.

Those who buy and never look at their portfolio face a similar situation to the philosophical experiment – If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? I recently learned that my mother-in-law is holding stocks her husband bought in the 1960s!

The practical reality is that most people do look at their portfolios with some regularity. Some investors hire professional wealth managers to manage portfolios. Other investors are hands-on and like to manage their own portfolios. The nature of the investor and how closely she manages her portfolio drives the frequency of market observation.

That observation frequency in turn allows you to divine if the VNQ had a 42% drawdown in Feb- March 2020 or a 20% selloff in the month of March 2020. The magnitude of your perceived drawdown determines if and when you will rebalance your portfolio.

Month-end/Calendar Driven Rebalancing

Some investors choose a calendar-driven trigger, that is, month-end or quarter-end, to monitor the progress of the investment portfolio and to rebalance if the opportunity is available. With as little as four (quarterly) to twelve (monthly) observations in a year, they eschew the daily volatility of the market. The tendency of this group is to wisely let the dust settle before making substantial investment changes.

For those in the business of money management, it is important to lay out clear, systematic rules for employees, while simultaneously providing useful guidance to clients. Using calendar monthly returns for all investment decisions helps managers tell their investors, “In no calendar month were any of your funds down more than 20% in the year… As we have always maintained, we will only rebalance at the end of every month.” This is a strong and discretion-free message. It offers business continuity and peace of mind for the investor. It is practically very useful.

The shortcoming of the monthly rebalancing system is it most likely will miss rich intra-month opportunities to rebalance by buying Risky assets at attractive levels. For example, the VNQ made a low of ~ $57 on March 23rd, 2020. By March 31st, 2020, the VNQ had rallied 23% to ~ $70. Month-end portfolio watchers did not fret the intra-month lows, but they also missed an opportunity to buy cheaply.

Flexible Rebalancing

Since the 2007 housing crisis, we have seen that markets have been prone to increasingly extreme moves. This volatility makes more frequent rebalancing rewarding for some investors. Investors who choose to look at the market with daily frequency may still believe in the strategic power of long-term asset allocation, but they also want to take advantage if the market has overreacted in the near term.

As the far more eloquent Lady Gaga has said, “I want your ugly, I want your disease.” These investors closely monitor and often rebalance their portfolios in months with extraordinary volatility.

While calendar-based rebalancers have the convenience of dates to reallocate between assets, daily market observers get no such respite. They need other tools. One tool such investors can use is to rebalance at every 10% selloff in the Risky asset. In an extreme case, when peak to trough asset drawdowns start to approach the worst-case scenario for a major asset, such levels can be used to reallocate aggressively (as much as one’s risk appetite will allow). The date of the month is immaterial. All investors have a higher rate of success when they stick to a system that best fits their natural tendencies. The daily market observer must be careful not to overtrade.

What is the psychological importance of rebalancing during severe drawdowns?

Firstly, let us remember that to make money in investing, we must be greedy when others are fearful. The person selling VNQ at $56 is probably the same person who bought it at $99. Their fear is our opportunity. But we can only take advantage of this opportunity if we act. Sitting around twiddling our thumbs ain’t gonna help. Rebalancing will.

Second, every investor gets psychologically destroyed in sharp drawdowns. Let us think: what can we do to raise our game in such depressing moments? We can think of the future and what we can do today that will be helpful in the future. Rebalancing, calculating new asset allocations, deciding what to buy, what to sell, and tax loss harvesting are activities that can use the portion of our brain that deals with analytical work. Slowly, our emotional state can step back, and our analytical self can take control. The magic starts happening when we start believing in ourselves again.

Today’s market and conclusion

The current market drawdown is as good a time as any for an opportunity to apply the gift of rebalancing. Year-to-Date the US Equities benchmark is down about 9% and US Equity REITs are down 11%. If anyone has any doubts, the year 2022 has made it clear that no investor knows what the future holds. Trying to rationalize and analyze economic and political events is nice, but what does it do for the portfolio? Meanwhile, using the drawdown opportunity to rebalance as appropriate is fully actionable, and can be an investor’s best friend. Work out a system that is right for you and stick to it.

In this article, I have tried to show that during highly volatile periods, definitions of drawdowns will differ. This is to be expected. Different investors design systems based on what works for them. It is not the definition of the drawdown that matters, it is what you do during the drawdown that can help your future financial self.