Dear friends,

It’s fall! We’re back! And we hope you are, too.

Well, it’s “meteorological fall” anyway. “Astronomical fall” (or is it “anatomical fall”? I can’t recall) holds off until September 22. With two classrooms full of students (one studying Propaganda with me, the other Advertising and Consumer Culture), my brain assures me it’s really fall. Their choice of attire (short, light, and often shredded), contrarily, suggests that they’re still holding on to summer.

And bless them for it!

Things I Learned While Trying to Avoid Doing Actual Work

It’s all a game to you, isn’t it!?! Actually, with our newest cohort of investors, it sort of is. CNBC surveyed 5,530 adults in August and discovered:

- 35% of investors aged 18-34 say they get investment ideas from social media, with smaller numbers of investors selecting “friends and family,” financial guidance websites, and news media.

- Three-fifths of the young retail investors surveyed said they began investing in 2020 or 2021 when they were bored and trapped at home.

- When asked why they started investing, 12% said because it “feels like a game.” 27% said “it’s exciting,” and 24% said it’s easy to do on their own. (from Amy Graffeo, Business Insider, 8/23/2021)

“Social media,” you say? Yep. Lovely clueless people on TikTok are making tens of thousands of dollars a day, in some cases, and hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, in others, cheerleading for “fun and exciting” stocks. The Wall Street Journal’s Robbie Whelan describes them this way:

Now, a new generation of Jim Cramers has risen up on social media with massive followings as guides to these market newbies.

Many of these influencers have no formal training as financial advisers and no background in professional investing, leading them to pick stocks based on the whims of popular opinion or to dispense money-losing advice. (“The Social-Media Stars Who Move Markets,” 8/27/2021, a really striking piece of journalism albeit behind a paywall)

The one inviolable rule? “Never criticize a meme stock.”

How could this not end well?

September is, on average, the worst month for the S&P 500. It’s the only month where, on average, stocks decline. That said, October – a halfway decent month in terms of average performance – is the one renowned for all of the really spectacular crashes including 1929, 1987 (who now remembers Black Monday when the Dow dropped 22.6% – 7,980 points in today’s market – in a single trading session?) and 2008.

ETFs now hold over $9 trillion. With a “t.” Based on Morningstar data, the Wall Street Journal reports “Investors poured $705 billion into exchange-traded funds through the first seven months of the year, pushing 2021’s world-wide tally to a record $9.1 trillion” (Michael Wursthorn, WSJ.com, 8/12/2021) In the first seven months of the year, investors added $224 billion to Vanguard’s ETFs.

In a way, that highlights the argument we’ve been making for a long time: the mutual fund versus ETF fight is specious. First, traditional mutual fund advisors – Vanguard, BlackRock, State Street, Fidelity – completely and utterly dominate the ETF industry. Second, the rise of actively managed ETFs, especially the non-transparent ones, and the accelerating repackaging of existing mutual funds as ETFs means that the ETF wrapper is barely more than Mutual Funds 2.0.

The key debate remains to what extent to entrust your portfolio to relatively more active vehicles and to what extent to entrust them to relatively less active vehicles. (Index funds are not “passive,” it’s just that the active decisions are delegated to the index designers. And portfolios comprised of a dozen wacky micro-indexes – the Quality Plus Value Distilled Water and Cloud Technologies ETF – is not passive at all.)

When might you rationally consider mutual funds rather than active ETFs? Primarily if the investment universe you’re exploring – say international micro-cap value – has palpable capacity constraints since ETFs, unlike funds, cannot close to new investors.

When might you rationally consider more active rather than more passive? Four possibilities stand out. One, you’re looking for some sort of active risk mitigation. Two, you want to delegate the job of tactical asset allocation – of being a little more aggressive now and a little less aggressive at another time – to a professional but you don’t want to trust those decisions to a financial planner. Leuthold Core Investment, the fund or the ETF version, and Palm Valley Capital Fund are examples of funds where the managers love investing in stocks – but only when the risk-return calculus is in their favor. Three, you believe you’ve found a sufficiently distinctive strategy that outperforms passive counterparts and which can’t be arbitraged away; that is, you can’t design an index to do what they’re doing. David Sherman’s RiverPark Short Term High Yield Fund would be the poster child here. Four, you’ve found something that makes a world of sense to you and you’re comfortable with it. The key to investing success, after all, is discipline: finding a sensible strategy and sticking with it through thick and thin. If you’ve found a strategy that lets you go about your life without worrying about the market’s lunacy, you’ve won. Congratulations!

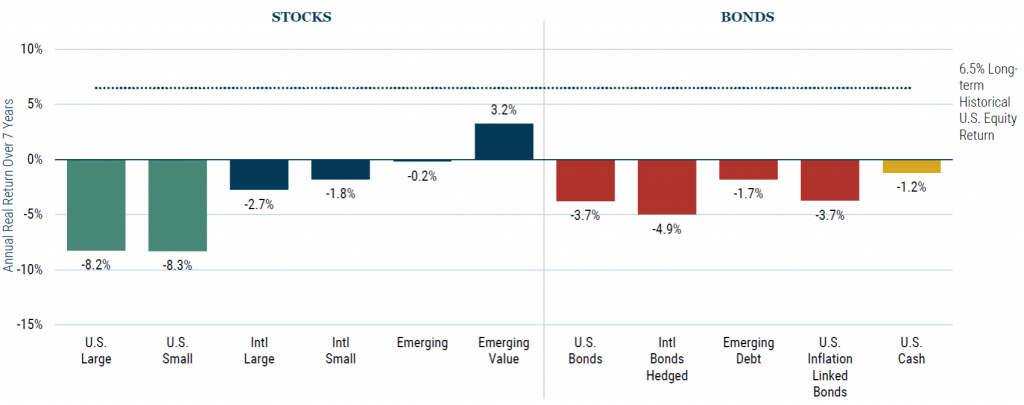

It might be worth looking at Japanese small value stocks. GMO, famously insistent that valuations matter and trees don’t grow to the sky, now project negative real returns on virtually every asset class over the next 5-7 years. Their model is based on the simple assumption that profit margins and stock valuations must, eventually, return to something like “normal.” If they do, the wild prices for all assets – and the hefty 11% annual returns that investors in an utterly vanilla 60/40 index fund have pocketed over the past decade – foretell A Great Reckoning.

Except, perhaps, for investors in small, undervalued Japanese stocks. “The massive snap-back in asset prices around the world has left it increasingly difficult to find attractively priced equities. Fortunately, those willing to look to Japan will find small cap value stocks to be an island of potential in a sea of otherwise expensive equity markets.” (Usonian Japan Equity and Asset Allocation Team, Japan Small Value, 7/2021).

“The combination of expected multiple expansion and rising ROC leaves Japan Value and Japan Small Value among GMO’s most attractive 7-Year Asset Class Forecasts,” they report.

Investors not interesting in paying GMO’s investment minimums – $500,000,000 on some share classes – might look at the Japan Smaller Capitalization ETF (JOF) which has a true small-value portfolio, Hennessy Japan Small Cap (HJPSX) which is more small-core or possibly Fidelity Japan Smaller Companies (FJSCX) which is more mid-cap but which, once upon a time, made me something like 250% in a single year. The caveat is that, YTD, they’ve only made a couple of percent.

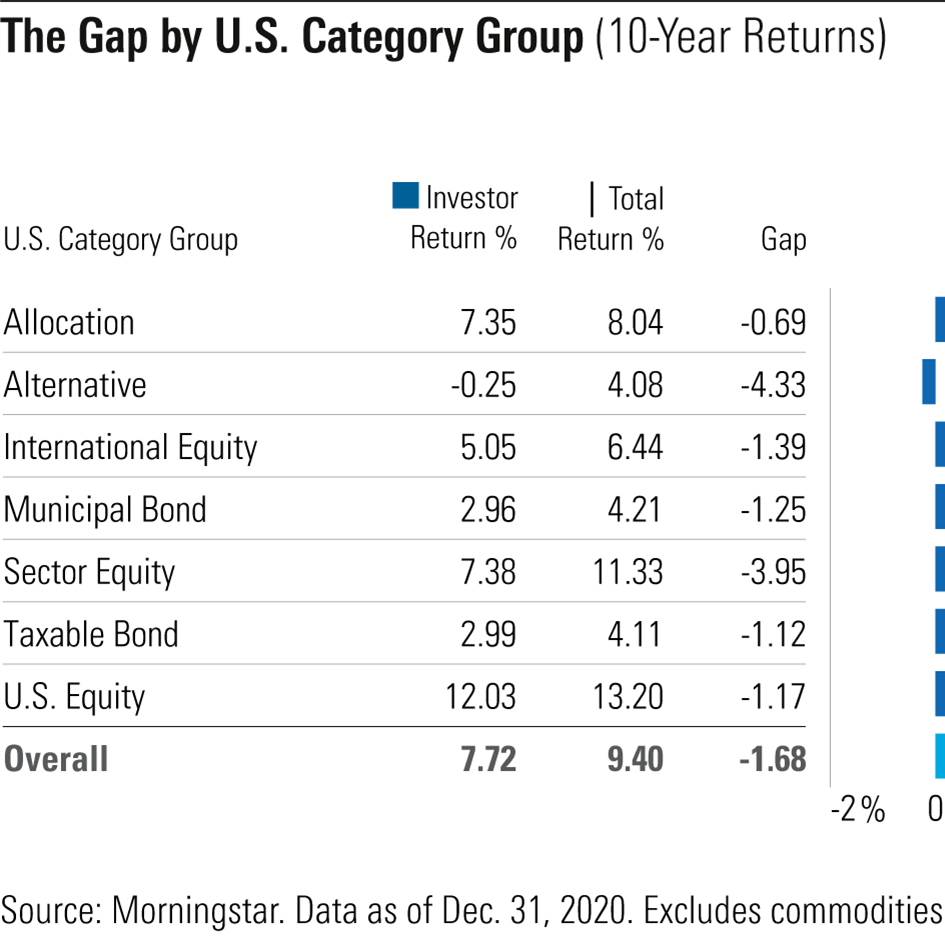

Investors continue to underperform their investments. In other contexts, we call that “shooting yourself in the foot.” Morningstar just released their latest “Mind the Gap” study that tries to compare the returns received by investors with the returns generated by their investments. It’s not pretty. Amy Arnott reports:

Our annual “Mind the Gap” study of dollar-weighted returns (also known as investor returns) finds investors earned about 7.7% per year on the average dollar they invested in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2020. This was about 1.7 percentage points less than the total returns their fund investments generated over that span. (Why Fund Returns Are Lower Than You Might Think, 8/30/2021)

The problem is simple and psychological: we see bright shiny objects – funds that made a lot of money for other people in the past (hypothetically an ETF, let’s call it “the Ark,” that made 152.82% last year) – and buy it in hopes that we magically inherit those wonderful gains. Then we discover that after great gains there are great pains (if, for instance, the Ark were in the red this year, trailing 100% of its peers and leaving new investors 1716 basis points behind a simple index), and we flee.

Morningstar’s breakdown of the size of the gap by investment type supports our argument about the folly of buying bling:

The greatest carnage came from investing in sector funds (cloud computing, oil, and so on) and alternative funds, almost all of which rely on arcane financial engineering and many of which rely on black-box algorithms, that investors have no hope of actually grasping. Mild-manned stock-bond hybrid funds, on the other hand, have the smallest gap.

FOMO is mostly MO. Part of the craze for “investing is a game” funds was manifested in the FOMO ETF. FOMO was designed to give you access to all of the cool stuff – SPACs, crypto, volatility ETFs, inverse volatility ETPs – that you were otherwise missing out on. Meh. Since its launch, the fund is up 3.4% and the MSCI world stock index is up 5.4%. I’m not sure that you’re missing much, but I am sure that the latest wave of silliness – Anti-ARKK, MEME, cannabis, dynamic cannabis, cloud cannabis, crypto cannabis – will serve you no better.

Vanguard is making $580 million a month from the management fees on its nearly $8 trillion in global assets, according to Dan Wiener of The Independent Adviser for Vanguard Investors (9/2021). By way of context, there are nearly 4,000 mutual funds (3927) – including 310 five-star funds – smaller than Vanguard’s monthly earnings.

The way we tell stories to ourselves is incredibly powerful. I’ve been reading Frank Rose’s The Sea We Swim In: How Stories Work in a Data-Driven World (2021). It’s a maddeningly rich, interesting book. Rose, a former journalist (we forgive him), argues

The way we tell stories to ourselves is incredibly powerful. I’ve been reading Frank Rose’s The Sea We Swim In: How Stories Work in a Data-Driven World (2021). It’s a maddeningly rich, interesting book. Rose, a former journalist (we forgive him), argues

For decades, psychologists didn’t deign to study stories—they were considered frivolous, unworthy of serious study. But … narrative thinking is our default mode—it’s what we engage in all the time. It’s gossip. It’s television. It’s the movies. It has little to do with reason and everything to do with emotion. As a species, we humans have an enormous investment in the idea that we are rational creatures, that we’re far too smart to be persuaded by something so emotional as a story. Unfortunately, our attachment to this idea is much more emotional than it is rational.

Economists made believe that we are “rational actors,” wild stock market swings and tulipomania notwithstanding. Ad executives used to talk about the “unique selling proposition,” the benefit that would give their product an edge over all competitors—as if consumers would automatically make the right choice when confronted with the facts. But deep down, we all realize that reason is an aspirational goal. Maybe that’s the real reason scientists were so reluctant to study stories; maybe they were afraid of what they’d find.

Rose cites and connects an awful lot of research across a half dozen fields that, collectively, helps us understand how we talked ourselves into our current predicament.

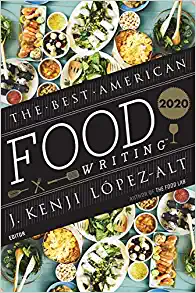

If you haven’t quite escaped summer mode yet, Chip and I are also reading – aloud to one another, as is our habit – from Kenji Lopez-Alt’s collection, The Best American Food Writing 2020. It’s not a cookbook, it’s a collection of essays from a dozen sources whose subjects range from racism in restaurant reviews to exposes on the air content of ice creams. We’ve enjoyed it, mostly, though some of the “what it’s actually like to work in a high-end restaurant kitchen restaurant” is a tiny bit soul-crushing.

If you haven’t quite escaped summer mode yet, Chip and I are also reading – aloud to one another, as is our habit – from Kenji Lopez-Alt’s collection, The Best American Food Writing 2020. It’s not a cookbook, it’s a collection of essays from a dozen sources whose subjects range from racism in restaurant reviews to exposes on the air content of ice creams. We’ve enjoyed it, mostly, though some of the “what it’s actually like to work in a high-end restaurant kitchen restaurant” is a tiny bit soul-crushing.

Thanks, as ever …

To the folks who read and support the Observer, whether through monthly contributions, occasional gifts, MFO Premium memberships, thoughtful notes or interesting suggestions. You all matter, more than you know.

Thanks then to Wilson and the folks at S&F Investment Advisors and to our hearty, faithful PayPal subscribers: Greg, William, William, Brian, David, and Doug.

I’ll get a chance to speak (virtually) with the folks at the Orange County chapter of the AAII in the middle of September. “Stillness Is the Key: The Indolent Investor’s Guide to Sanity & Success.” I’m looking forward to it.