“Snow on the pines

thus breaks the power

that splits mountains.”Otaka Gengo Tadao (大高源五忠雄,one of the forty-seven Ronin).

Last month, David Snowball opined on Morningstar’s John Rekenthaler’s requiem for mutual funds. And while David agreed with Rekenthaler that the end of the fund industry was not imminent, both feel that it is inevitable. I have felt that to be the case for some time. Rather than be the Cassandra who predicts the end of the happy days for a new generation of fund managers and analysts (not their investors) I chose to sit quietly in the weeds until the signs were obvious. Seeing daily notices of fund closings and consolidations, in conjunction with fee reductions and personnel reductions, we are at a tipping point. Younger generations of analysts and portfolio managers are going to have to forego dreams of zooming around the Great Lakes or some other bodies of water in their yachts.

As investment volatility (equities and fixed income) has increased, we also see the harbingers of change in the environment for funds, specifically the world of taxes and regulation. On almost a daily basis, one sees articles about the needs at the state level for increased revenues. The suggestions to solve the tax revenue shortfalls include raising capital gains tax rates, capping the deduction for qualified dividend income and, raising marginal rates, and/or placing special levies on high-income taxpayers.

There have been, in addition to the pandemic, multiple demands on executive time which are distractions from the core goal of running the business. As it is now proxy time, another data point that one should examine is the extent to which public companies have had to dedicate resources away from the goal of simply running the business for the benefit of the shareholders. The proxy should tell you to what extent there are now reporting requirements or requests relative to ESG criteria, as well as the justification for being in a particular industry or line of business. Those requirements or requests are sourced by regulators and/or consultants working on behalf of investors (especially institutional).

That is on top of the usual investor relations events that take place in a fiscal year. How many calls or meetings are scheduled, taking up how many hours or days of the chief executive officer or chief financial officer? How much time is required for quarterly earnings presentations and conference calls, all of which are pre-scripted and rehearsed? The nature of these matters and their calls on executive time is such that one wonders what the actual time is that is devoted to running the business. Or rather, is the function of the chief executive officer and chief financial officer positions such that they are there to protect or screen the operators at a functional level from being pulled away from devoting their full time and attention to the corporation’s lines of business?

My conclusion as I have thought about taxes? I am of the mind that individual investors should only own mutual funds in tax-free (IRA, 401(k), or pension) accounts. Are there exceptions? Yes, for things such as ultra-short, low-duration, fixed-income funds that serve as money market proxies with slightly higher risk levels. And in a more normal rate environment, money market funds.

I also am becoming more of the mind that the maximum ability to devote time to properly run a business, without the distractions that appear to take away from the profit maximization goal is to be found in private equity situations rather than public equity. My sources involved with private equity tell me that the private equity firms have tended to concentrate on and develop specialties. And resultingly they concentrate their efforts in those situations where they have a skill-set advantage, allowing them to be laser-like focused. Private equity boards and management teams are not cluttered up with individuals or managers who are not attuned to making the business as profitable as possible.

For those who are skeptical of my arguments, I suggest during proxy season that you examine the biographies of the individuals serving on the various boards of directors of public companies that you are interested in or in which you already hold an investment. Upon such examination, you should be able to identify and distinguish between those directors who are there for window dressing, and those who are contributing to the process. Another metric to check is the size of the board. Even for huge mega-cap organizations, boards larger than twenty are probably bordering on being dysfunctional. A final metric to examine is the number of boards an individual is serving on in addition to the one you are examining. More than two is probably too many for non-management directors to be effective. Board service should not be viewed in the context of a retired executive or investor assembling a “board portfolio” of seats in order to supplement his or her retirement income.

Interest Rates and Inflation

Last week we saw the fear of rising interest rates creep into the investment marketplace as the yields on the 10-year U.S. Treasury increased, giving lie to the stability promised by Federal Reserve Chairman Powell. Along with that came a seven-year Treasury auction that has been described selectively as “the worst in history” in terms of liquidity and the clearing price that was required.

While the Federal Reserve has spoken in terms of a 2% inflation target, the market seems to be anticipating an overshoot, with the Consumer Price Index possibly going over 3%. The work of The Institutional Strategist suggests that given commodity pricing surges, we could see the Producer Price Index north of 6%. That degree of rising inflation ultimately will be priced into both bond yields (increasing) and equity prices (decreasing). If there is one thing we have seen recently, it is that the days of straight-line movements and extrapolation are over for now. Look for the volatility in various asset class markets to continue. Also, look for commodity prices (copper, steel, agriculture, and energy) to continue to increase given demand. Finally, given the example of Texas over the last few weeks, now is not the time to run out and trade the internal combustion engine auto for the electric vehicle.

A Reading Suggestion

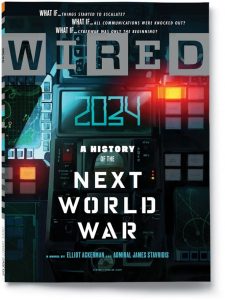

I read in the February 2021 issue of Wired an excerpt from 2034: A Novel of the Next World War by Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis, to be published on March 9, 2021. For those who know little about proactive cyber warfare and electromagnetic pulse weapons, I suggest getting the book. It will give you an appreciation of the dangers of too much technology, especially when unintended consequences are not considered. For the skeptics, I will point out that the most recent aircraft carrier to join our fleet, with new technology without the bugs ironed out, has catapults that can’t launch planes and elevators that have trouble moving planes and weapons between decks. And we also have a class of littoral combat ships that appears to have problems with the new engine gearing systems.

I read in the February 2021 issue of Wired an excerpt from 2034: A Novel of the Next World War by Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis, to be published on March 9, 2021. For those who know little about proactive cyber warfare and electromagnetic pulse weapons, I suggest getting the book. It will give you an appreciation of the dangers of too much technology, especially when unintended consequences are not considered. For the skeptics, I will point out that the most recent aircraft carrier to join our fleet, with new technology without the bugs ironed out, has catapults that can’t launch planes and elevators that have trouble moving planes and weapons between decks. And we also have a class of littoral combat ships that appears to have problems with the new engine gearing systems.