What’s the worst that could happen? Managers’ own words on liquidity risks

Liquidity seems like an awfully esoteric concern, something akin to “coverage ratios” or “yield to call calculations.” In general, it feels like background noise.

Your fund managers disagree. New research estimates that 50% of high-yield funds and, more importantly, 15% of all fixed-income funds are vulnerable to a liquidity crunch. To understand what that means, you first need to understand that “liquidity” means. If you need to polish up your understanding of the term – or your ability to explain it to clients – start with the section entitled What’s Liquidity? If you’re rock solid on the concept, then jump ahead to Welcome to a Liquidity Crisis.

What’s “liquidity”?

“Liquidity” is a really simple concept. It’s your ability to convert an asset you own to cash. If you have a $5 bill, you can walk into pretty much any store or bank in America and trade it for five ones. That’s a purely liquid asset. At the other extreme, trading in your time-share condo for cash is ridiculously hard and time-consuming, and you might end up writing off 50% of your investment just to cash out. That’s called an “illiquid asset.”

In order to liquidate an asset, you need two compatriots: you need someone with cash who’s willing to pay about what you’re looking for and you need someone to coordinate you and your buyer; that’s the middleman who hands you their cash, takes your asset in exchange and then sells your asset to the end buyer. That person’s called a “market maker.” Market makers have no earthly interest in owning the thing you’re selling; they just want to be the conduit between you and someone who will very promptly pay them a predictable amount for your asset.

Some assets are highly liquid; that means that there are always lots of prospective buyers out there willing to trade their cash for your assets. Examples of highly liquid assets are bonds or bills issued by the US Treasury (backed by “the full faith and credit” of the government) or stocks issued by blue-chip corporations.

Bonds issued by an economically challenged firm? Sort of liquid in good times. Given time and effort, you can probably get some sort of agreement with a potential buyer. But what happens to that same bond if the market (or the economy) suddenly sputters? The economically challenged issuer might see its chances of survival (hence, of repaying its bonds) go from 60% down to 40%. The potential buyers might well be spooked and be reluctant to shell out anywhere near the full price. Market makers might well be spooked about their ability to recover the money they’ve fronted and be reluctant to handle your sale. In short, unless you’re willing to sell for pennies on the dollar, you might find that you can’t sell at all.

In summary: Some assets are almost always easy to sell (T-bills). Some assets are almost always hard to sell (your time-share). Some are deceptively easy to sell when everything’s going right but near impossible to unload when it’s not (say, shares of ultra-microcap Paradise Inc. PARF which makes the candied fruit in fruitcakes and trades about 600 shares/day).

Welcome to a liquidity crisis

“Liquidity rarely matters, but when it does, it’s all that matters.” Savita Subramanian, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s equity and quant strategist

Why bring the subject up now? Good question!

There have been structural changes in the markets that impair liquidity.

Liquidity markets require two sets of actors with ready access to cash: intermediaries or market-makers and ultimate buyers.

Market-makers are firms that exist to pair buyers and sellers. When you offer shares of your ETF for sale, a market maker buys them from you at a tiny discount to NAV and sells them to an interested buyer at a slightly higher price. Their profit resides in the often-tiny spread between what you sell a share for and what the next person buys the share for. Market-makers have a limited pool of money so they need to believe they can sell your share almost immediately for a predictable price. If they’re not sure they can sell fast and for a predictable price, they’re going to protect themselves by (1) not buying your share or (2) buying it at a discount to what you think it’s worth. As uncertainty grows, so do those two tendencies.

Structural changes have reduced the capital available to market-makers. The Fed is policing the size of banks’ capital reserves, and higher reserve requirements mean less cash allocated to market makers. As spreads narrow, which happens in bull markets, market-making becomes less profitable and banks allocate less there. So market-makers can handle high volumes if and only if the market is acting normal; as it becomes volatile, each trade becomes potentially riskier for them and their ability and willingness to handle high “sell” volume for iffy securities – from junk bonds and “barely-above junk” bonds to real estate and thinly traded microcaps – collapses.

The financial system used to have other reliable fallbacks which guaranteed liquidity for the best customers (read: Fidelity). Ed Studzinski notes that,

… in days of old, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and their ilk used to be prepared at the end of a trading day, to hold a position overnight for good clients, recognizing that they should cut the price enough that they were willing to pay so that any loss they might incur overnight was more than covered by the margin in the price they paid … [not too long ago] they stopped being willing to hold securities overnight that were not liquid that they would sell the next day – in a nutshell, they did not want them on their books, given the complexities of the derivative and other positions they were holding, especially for their own accounts.

Most mutual funds (and we have written about this) have lines of credit with banks to cover the unhappy situation where they have more withdrawals than cash on hand. “Committed lines of credit” are more-or-less guaranteed to be there, but you pay a higher fee for the security; many funds rely on “uncommitted lines of credit” where they will lend to you if they can, but are assuming the Fed will flood the market with liquidity to keep a meltdown from happening.

Ultimate buyers are the counter-parties, the people with cash and a willingness to buy from you at a price you can live with. If there’s a wave of selling, who’s available to buy? Traditionally, it might be value investors with lots of “dry powder” or mutual funds with cash reserves. As those two sets of buyers shrink, who takes their place? By definition, it’s not the managers of passive funds; they’re forced to sell when the market drops, they have neither the mandate nor the resources (remember, they’re fully invested all of the time) to buffer a fall. That means more and more of the responsibility lies with hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, private investors and the owners of various dark pools.

So, liquidity may be increasingly impaired. That was illustrated in September. Much of this liquidity stuff takes place in something called “the repurchase market,” known slangily as “the repo market.” The repo market serves as a source of short-term cash for the financial system; a mutual fund might borrow a few billion overnight, surrendering some of their portfolio securities as collateral. It takes about a trillion dollars a day to keep the repo market working and, on September 16-17, it ran out of liquidity. The Fed didn’t see it coming and hadn’t prepared for it. They hurriedly stepped in, making tens of billions available on short notice, to keep the short seizure from becoming a major crisis. The Fed, since then, has been pouring in additional billions to keep the market working and may need to re-establish a program to deal with other shortages. Ed notes, too, “that the U.S. Treasury market, which is supposed to be the most liquid in the world, has on occasion also seized up and become relatively illiquid in terms of the size trades you could put through without moving the bid-ask spread.”

Exceptional investors have gone hoarse yelling about the risk.

Quite beyond Ed Studzinski’s long series of reflections on liquidity losses, several other “A” tier managers or former managers have been speaking out. Tad Rivelle, TCW’s chief investment officer, a guy responsible for $175 billion in fixed-income assets and Morningstar’s 2005 Fund Manager of the Year recently published “Why a Liquidity Crisis Is Heading to a Market Near You” (September 2019). Rivelle’s argument is that the quality of the bond market – and the transparency of the financials for bond issuers – has taken a dramatic turn for the worse.

Traditionally, leveraged borrowers had this choice: borrow in the high yield bond market and live by the disclosure and reporting standards of the public debt markets. In the alternative, if management preferred to adhere to a lesser standard of disclosure, the company could issue in the (private) loan market and subject itself to a battery of covenants designed to limit the ability of management to engage in risky or lender unfriendly actions. Thanks to the central banks, borrowers in this cycle no longer had to choose: they could obtain cheap loans without agreeing to restrictive covenants nor providing on-going financial disclosure.

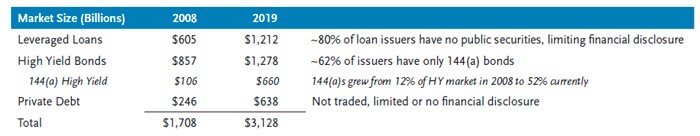

Hence, not only have the debt markets ballooned in size, but the growth has come disproportionately from those segments of the debt market where financial disclosure is poor:

Source: JPM, Bloomberg Barclays, Prequin

While a paucity of financial disclosure is not problematic during a bull market for credit, it is a defining feature of a liquidity crisis during a bear market. Human beings are naturally inclined towards fear–even panic–when they are unable to obtain the information they deem critical to their (financial) survival.

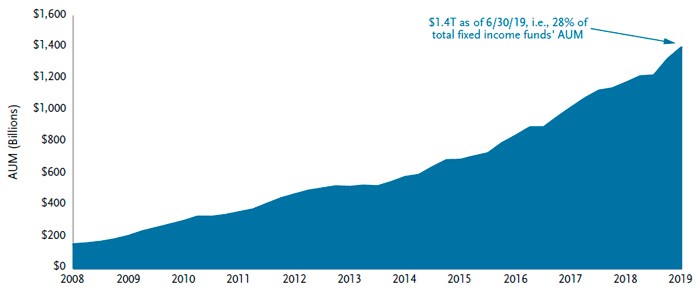

The problem, in his mind, is that passive fixed-income funds have been scooping up sludge because the sludge is part of their index. What happens, he asks, when a recession turns the sludge toxic and antsy investors suddenly want the security of cash?

Thus far, in this cycle, passive funds have exploded in size. Anyone wonder what might happen should passive funds become large net sellers of credit risk? In that event, these indiscriminate sellers will have to find highly discriminating buyers who–you guessed it–will be asking lots of questions. Liquidity for the passive universe–and thus the credit markets generally–may become very problematic indeed.

Passive Fixed Income Funds (Including ETFs)

Source: Morningstar, TCW

He concludes that you might want to gather your security blanket now, while you still can:

Capital markets are reflections of human nature. So, until the robots take over, fear and greed will remain in the DNA of asset markets and result in bouts of liquidity wherein “anything goes” alternating with periods where “nothing” is believed. As such, while holding a portion of your net worth in such dull investments as cash or Treasuries forgoes some bragging rights, history suggests that it could be among the most important allocation decision you make in a late-cycle environment.

Bob Rodriquez, as befits a retired titan of finance, is rather more outraged. Mr. Rodriquez is one of only two managers to win Morningstar’s fund manager of the year three times (1994, 2001, 2008) and the only manager to win in both the equity arena (for FPA Capital) and fixed income (for FPA New Income). He was interviewed by Robert Huebscher in September 2019, with the edited version appearing in Rob’s Advisor Perspectives under the title, “The Fed is Clueless.”

Mr. Rodriquez’s argument might be summarized as “you’re all fools and you’re going to suffer a lot for a long time.” He warned a decade ago, in the wake of the Fed’s unprecedented interventions in the market, that the Fed was engaged in wishful thinking. They could offer up free money, which underwrote – and hence encouraged – bad behavior on the part of managers and investors. They issued ever-greater quantities of ever-iffier debt, and used to the proceeds for financial engineering – share buybacks, underwriting dividends, buying competitors – rather than for productive purposes. In consequence, he argued, the Fed stimulus wouldn’t achieve its fundamental goal of strengthening the economy. He believes that as the market gets shakier, the Fed’s interventions will become bolder, broader … and less effective. His recommendation, broadly speaking, is to strip your portfolio down to the best of the best.

When one believes the optimal capital structure is for elevated levels of leverage, one can be reasonably assured they are succumbing to the theory that “this time is different.” When this credit cycle ends, it will be among the worst, if not the worst, since the Great Depression. With such a high level of investment-grade corporate bonds hovering above a high-yield credit rating, in the upcoming recession, many fixed-income fund investors will be surprised by how their “investment” grade bond funds perform poorly. They should gain a better insight about the credit quality mix of their respective funds NOW!

Laura Kodres, a former division chief at the International Monetary Fund’s global financial stability unit, argues that the “hedge funds for the masses” philosophy, which makes complex and sometimes inexplicable magic wands available to the average investor, is likely to see enormous liquidity challenges when everyone tries to unwind their derivative positions simultaneously:

“There is a sense in which retail investors should have some opportunity to take risks that were previously just the purview of high-net-worth individuals,” Kodres told MarketWatch in an interview. But that democratization, she said, also has resulted in financial products that may be unable to sell their underlying assets quickly, if shareholders get spooked and they rush to pull cash out.

“To be fair, probably somewhere in the fund documents it says there is liquidity risk and redemptions are not guaranteed within 24 hours,” she said. “But I’m not sure everyone has read that fine print as closely they should.”

Her concerns lie not with standard funds that buy stocks that frequently trade on regulated exchanges, but with the swell of mutual funds that now hold less liquid assets, namely corporate debt, emerging-market bonds, and real-estate exposure that can take days (or months) to unload in a jittery market. (“Investors putting too much faith in mutual funds to return money in a panic, former IMF financial stability analyst says,” MarketWatch, November 12, 2019)

Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney, warned that investment funds that hold illiquid assets, but promise investors daily liquidity, were “built on a lie” and could pose systemic risks.

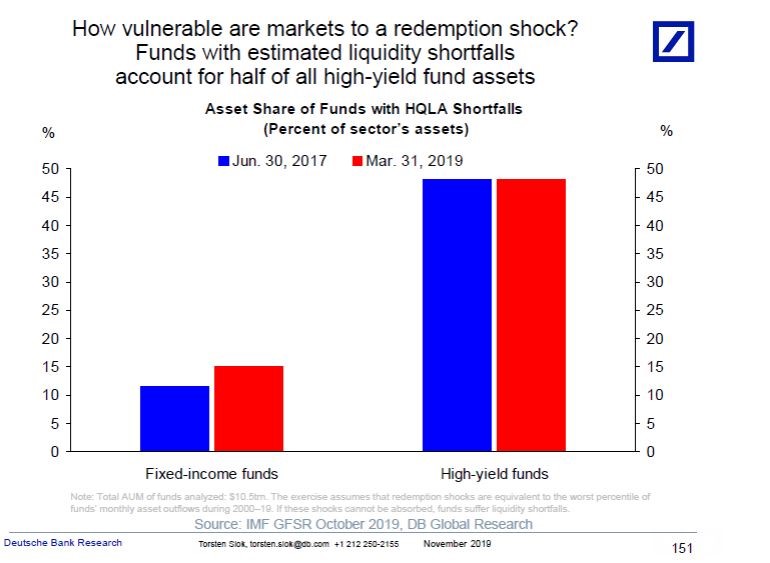

How likely are you to face such a risk in your own portfolio? Pretty likely, if Deutsche Bank is right. Deutsche Bank’s chief economist Torsten Sløk published research in November showing half of funds with high-yield assets would face liquidity shortfalls if managers experience a repeat of the worst redemption shocks felt between 2000 to 2019.

Source: Deutsche Bank

The left-hand bars might be scarier: perhaps 15% of all fixed-income funds – including “investment grade” vehicles – might face similar challenges.

What your managers are telling you about the risks you confront

Not all funds discuss liquidity as a principal risk, and some funds highlight liquidity in some years rather than others. In general, fixed income funds with a high-yield or international component, small caps and anyone reliant on the derivatives markets tend to share warnings, which are mostly unread.

We searched the SEC website using “485a” and “liquidity risk” as our search terms. Those typically led to prospectuses (Form 485a) and liquidity discussions. We then sampled the first 20 results, not all of which represent the most recent version of the prospectus.

Why aren’t they the most recent ones? Uhhh … blame the algorithms?

For folks who have not read the liquidity risk disclosures in bond fund and ETF prospectuses, let me share some of their clearer warnings:

Met West: We “may not be able to sell at all”

Liquidity Risk: the risk that there may be no willing buyer of the Fund’s portfolio securities and the Fund may have to sell those securities at a lower price or may not be able to sell the securities at all, each of which would have a negative effect on performance. Over recent years, there has been a dramatic decline in the ability of dealers to make markets, which can further constrain liquidity and increase the volatility of portfolio valuations. High levels of redemptions in bond funds in response to market conditions could cause greater losses as a result. Past changes in regulations such as the Volcker Rule may further constrain the ability of market participants to create liquidity, particularly in times of increased market volatility. Met West Flexible Income 2018 prospectus,

TCW: Us too, “may not be able to sell at all”

Liquidity risk: the risk that there may be no willing buyer of the Fund’s portfolio securities and the Fund may have to sell those securities at a lower price or may not be able to sell the securities at all, each of which would have a negative effect on performance. TCW Concentrated Value Fund, 2016 prospectus

Russell, alternately the price we can get “may fall dramatically”

Liquidity Risk: Liquidity risk exists when particular investments are difficult to purchase or sell. The market for certain investments may become illiquid under adverse market or economic conditions independent of any specific adverse changes in the conditions of a particular issuer or a security’s underlying collateral. In such cases, the market price of certain investments may fall dramatically if there is no liquid trading market. Russell Small Cap High Dividend Yield ETF, 2012 prospectus

Vanguard, even if we buy liquid assets, they may “suddenly become illiquid for an indefinite period of time”

Liquidity risk is the chance that the markets, assets, and instruments in which the Fund invests are, or may become, illiquid. The advisor expects that the Fund generally will seek to invest in liquid markets, assets, and instruments, although the Fund may have the ability to invest a portion of its assets in markets, assets, or instruments that are or may become illiquid. There is no assurance that investments that were liquid when purchased will not suddenly become illiquid for an indefinite period of time. Vanguard Commodity Strategy Fund, 2019 Prospectus

PowerShares, derivatives “may not always be liquid”

Liquidity Risk. The Fund will invest in derivatives and other instruments that may be less liquid than other types of investments. Investments that are less liquid or that trade less can be more difficult or more costly to buy, or to sell, compared to other more liquid or active investments. This liquidity risk is a factor of the trading volume of a particular investment, as well as the size and liquidity of the market for such an investment. The derivatives in which the Fund invests may not always be liquid. This could have a negative effect on the Fund’s ability to achieve its investment objective and may result in losses to Fund shareholders. PowerShares Multi-Strategy Alternative Portfolio LALT, 2014 prospectus

iShares, real estate is like small caps, “relatively illiquid [with] abrupt or erratic price fluctuations”

Liquidity Risk. Investing in Real Estate Companies may involve risks similar to those associated with investing in small-capitalization companies. Real Estate Company securities, like the securities of small-capitalization companies, may be more volatile than, and perform differently from, shares of large-capitalization companies. There may be less trading in Real Estate Company shares, which means that buy and sell transactions in those shares could have a magnified impact on share price, resulting in abrupt or erratic price fluctuations. In addition, real estate is relatively illiquid, and, therefore, a Real Estate Company may have a limited ability to vary or liquidate properties in response to changes in economic or other conditions. iShares Evolved U.S. Healthcare Staples ETF (IEHS), 2018 prospectus

Here’s the one to post on your fridge:

iShares ESG 1-5 Year USD Corporate Bond ETF (SUSB), 2017 prospectus

Liquidity Risk. Liquidity risk exists when particular investments are difficult to purchase or sell. To the extent the Fund invests in illiquid securities or securities that become less liquid, such investments may have a negative effect on the returns of the Fund because the Fund may be unable to sell the illiquid securities at an advantageous time or price. To the extent that the Fund invests in securities with substantial market and/or credit risk, the Fund will tend to have increased exposure to liquidity risk. Liquidity risk may be the result of, among other things, the reduced number and capacity of traditional market participants to make a market in fixed-income securities or the lack of an active market for such securities. Liquid investments may become illiquid or less liquid, particularly during periods of market turmoil or economic uncertainty. Illiquid and relatively less liquid investments may be harder to value, especially in changing or volatile markets. Although the Fund primarily seeks to redeem its shares in-kind, if the Fund is forced to sell underlying investments at reduced prices or under unfavorable conditions to meet redemption requests or for other cash needs, the Fund may suffer a loss. This risk may be magnified in a rising interest rate environment or other circumstances where redemptions from the Fund may be greater than normal. Other market participants may be attempting to liquidate fixed-income holdings at the same time as the Fund, causing increased supply of the Fund’s underlying investments in the market and contributing to liquidity risk and downward pricing pressure. There can be no assurance that a security that is deemed to be liquid when purchased will continue to be liquid for as long as it is held by the Fund.

Bottom Line

I am not particularly apocalyptic, in general. I worry about things but try to keep a healthy distance from panic: humanity will survive, the Republic will survive, the markets will rise (and fall) again, the sun will rise again.

None of that excuses ignorance. As investors, we need to be aware of the risks we’re taking (or that others are taking on our behalf) and we need to be weather the worst-case outcomes that our choices engender. “Weathering” is starts with knowledge.

-

- What’s your asset allocation? How much downside does an allocation of that variety risk in a major correction?

- What have your managers said about how they view stewardship of your money? Do they imagine themselves as risk managers, or returns managers?

- To what extent can you explain what your managers actually do? Or what biases are embedded in your passive product?

- To what extent are you exposed to the assets: 144a bonds, private placements, high yield, EM bonds, microcaps, bonds that have undergone or are near downgrade that pose the most risk in a liquidity crunch?

- To what extent have they recalibrated the portfolio’s risk exposure in the past year?

If your answers to yourself are some combination of vaguely and mumbled, you might want to take a bit of time while the sun is still shining to check the darker corners.

David Sherman, an eminently sensible investor, spent nine pages in his last shareholder letter reviewing the risks that were, he believes, poorly accounted for by investors and the steps that he and his team have taken to de-risk his portfolios.

He closed his last shareholder letter with the same words we’ll share now: “Fall is here, winter is coming.”