There are a number of critical activities that most of us swear we’ll do tomorrow: schedule a colonoscopy, get to the gym, talk to your siblings, check your portfolio’s downside.

It’s time!

T.S. Eliot declared April to be “the cruelest month” (in “The Waste Land,” 1922). T.S. Eliot did not know much about the stock market. There, September is the cruelest month. While it has not been the site of most market crashes, since 1937 it’s been the single weakest month of the year. October has been the most volatile; site of the 1907, 1929 and 1987 crashes and the onset of the 2007-09 bear.

The reminder that you don’t need is that things remain parlous.

-

-

-

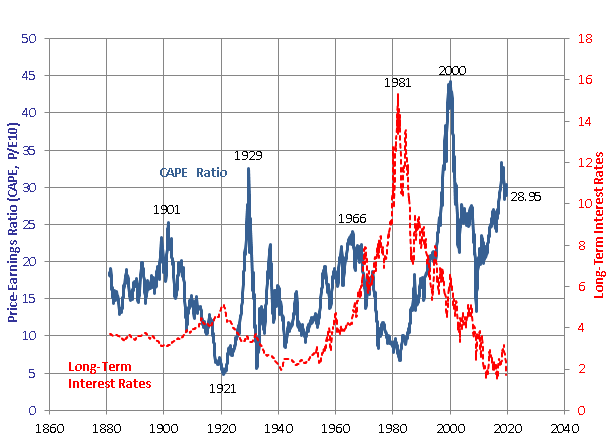

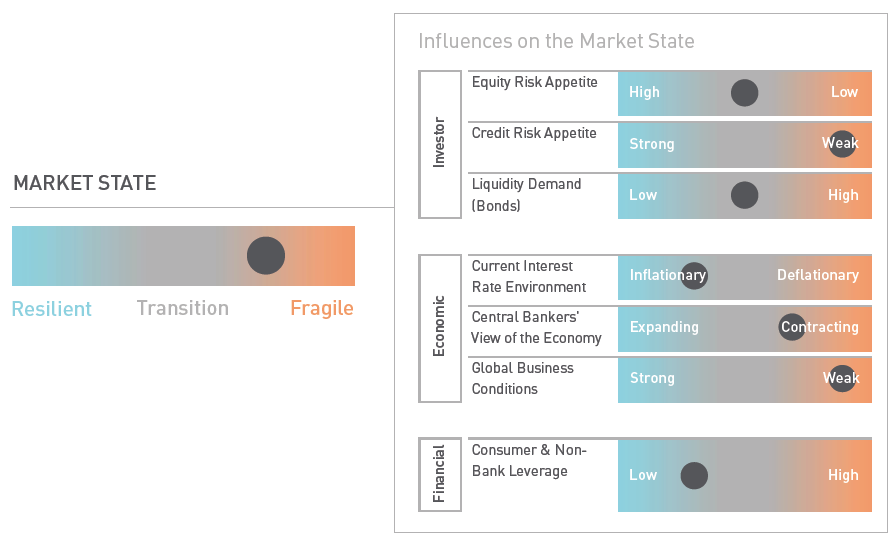

The stock market is … uhh, fragile. The stock market’s valuation, measured by its 10-year Schiller CAPE ratio is the third highest in its history, right about where we were at this point in 1929 though far below 1999. That’s against two problematic backdrops: government policy being set by tweet and deteriorating global economy buffeted by a trade war and the politics of nationalism. The folks at First Quadrant summarize it with this graphic:

They note that the “transition” from resilient to fragile lasts about six months, but markets that become fragile remain that way for several years. (FQ State of the Markets, September 2019). “Fragile” markets are typified, they claim, by susceptibility to shock, high volatility and a disconnect between risk and return.

-

The bond market is getting scary. Yes, I know: “nothing bad ever happens in the bond market.” That’s because bonds have been in a longer bull market, dating from the early 1980s when double-digit interest rates began to drop, than stocks.

The interest rate on 30-year Treasury bonds is at its lowest-level ever, though an asterisk would remind us that “ever” is “since 1977.” Still, the Treasury yield is lower than the S&P 500’s. This concern is separate from the widely discussed “yield curve inversions.” The effective duration of a 30-year Treasury at the end of August 2019, is about 22 years. That means that if interest rates rise by 1%, the price of a portfolio of 30-year Treasuries would fall by 22%. Institutional research firms Research Affiliates and GMO both estimate the US long bonds will post negative real returns over the next 7-10 years. At yet, investors are flocking to Treasuries in droves, which is what drives the yield down.

What are we to make of a desperate desire to lock-in small losses? At base, it’s the suspicion that everywhere else they look, they see larger losses looming. Bloomberg’s Brian Chappatta wrote a particularly sharp piece on the phenomenon this month.

In fact, for bond traders, 30-year Treasuries might just be the riskiest part of the debt market because they can usually be whipsawed by a [macro event] changes … However, this relentless rally at the long end shows that bond traders have completely let go of all fear of rising interest rates, stronger-than-expected economic growth or a sustained rebound in inflation. That should be as nerve-wracking to investors as the prospect of a global economic recession. After all, there’s a playbook for dealing with a downturn and an inverted curve. There’s no historical guide to sovereign debt yields across the world trading at, near or below zero.

Another reason that the move in 30-year yields is so striking is because it’s the exact part of the curve over which the Fed has the least control. (Brian Chappatta, “Forget the Yield Curve. The 30-Year Treasury Is Scary,” Bloomberg.com, 8/14/2019)

-

Why hedge your portfolio? There are two reasons:

-

Psychological: if you look at your portfolio, see that every single investment is losing money and that you’re down by some scary amount lately, it’s stressful and discouraging. It’s bad for your heart and may, if you react in haste, be bad for your long-term financial health too. If you’ve got some stuff that’s lost little or nothing, it’s easier to take a deep breathe, walk away from the “sell” button, and get back to prepping a nice Tuscan Risotto with Walnuts & Mushrooms (though I’d seriously consider using farro rather than rice) with your family.

-

Compounding: if your portfolio falls by a third, you haven’t gotten back to your break-even point until the market rises 50%. To illustrate what that means, let’s look at the performance of several fund categories over this entire market cycle, beginning in October 2007.

Lipper Category Stock exposure Maximum loss Recovery period Annualized returns Conservative allocation 30% 24 29 4.1 Moderate allocation 60% 35 38 4.6 Aggressive allocation 75-90% 51 64 4.5 Here’s one way to read that: a stock-heavy portfolio crashed by 51% and took over five years to get you back to where you started. Your willingness to ride that roller coaster rewarded you with 4.5% returns. A stock-light portfolio lost less than half as much, recovered in less than half the time, and still returned 4.1%.

Those are just the averages. The top stock-light funds (Vanguard Wellesley, Westwood Income Opportunities, MFS Diversified Income, Berwyn Income) all had returns that crushed the average stock-light fund in both returns (above 6% annually) and recovery (20 months, on average).

As we’ve noted several times over the years, there are three strategies for hedging your portfolio and we’ve nominated funds for your consideration in each strategy. Here’s our quick review and update.

Strategy One: Keep it simple

The simplest strategy is to have cash or cash-like investments in your portfolio. The upsides to holding cash: it doesn’t go down and the strategy is inexpensive to execute. The downsides of holding cash: it doesn’t go up and you’ve got to have the nerve to invest it at the precise moment that everyone else is peeing their pants.

The best plan is, as the common proverb has it, to profit by the folly of others. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book XVIII, sec. 31., circa 79 CE

Cash which you’re holding in anticipation of investing it in risk assets when the time is right is called “strategic cash.” Ideally, you’d like a positive real return when times are good and a very small drawdown when times are bad, since it won’t do you much good during a crisis if it’s evaporated. MFO has profiled a half dozen funds that might serve as strategic cash investments for you. Here’s their updated three-year record.

Maximum loss Annualized return Notes RiverPark Short-Term High Yield RPHYX -0.1% 2.9% Closed to new investors, unless you invest directly through RiverPark. This fund is in my portfolio and frequently has the highest Sharpe ratio of any fund in existence. Zeo Short Duration Income ZEOIX -0.4% 3.1 New name and lower e.r. in 2018 PIMCO Short Asset Investment PAIAX 0.0% 2.2 When PIMCO funds hold “cash,” this is the strategy they’re referring to. Payden Global Low Duration PYGSX -0.3% 2.0 Minimum of 40% non-US. Intrepid Income ICMUX -0.6% 3.1 A new management team in the past year; more opportunistic than the others, it posted a 25% gain in 2009 The starting point for learning more about any of those funds should be MFO’s profile of them. Those are located under the “Funds” tab atop this page.

Strategy Two: Delegate simplicity

This strategy suggests that you choose a fund where the manager is willing to hold cash when markets are irrationally expensive and to invest cash when markets are irrationally cheap. Upside: you don’t have to sit around wondering “is it time yet?” Downside: you will also surely hold a fund that makes you feel like an idiot for long periods. The frothy fun phase of the market can last for years, with returns utterly disconnected from reality. Holding a fund that’s earning 1% while everyone else is making 236% (really – one of my fund holdings in the 1990 had a 236% return one year for, let’s admit, no really good reason) will be annoying. That’s why so very few such funds survive. We nominated some worthies in our 2018 15 / 15 Funds essay, highlighting funds that made at least 15% in 2017 while holding at least 15% cash. We followed that up a year later with 15 / 15 Funds One Year On.

Managers who are unwilling to buy stocks when stocks are unreasonably expensive are known as “absolute value” investors (or dinosaurs).

Here’s the three-year snapshot for several distinguished absolute value funds.

Maximum loss Annualized return Notes FPA Crescent FPACX -10.5% 7.9% Crescent holds 28% cash currently. This fund is in my portfolio and manager Steve Romick is seen as one of the best in the business. Castle Focus MOATX -7.2 5.8 Currently holds 30% cash. Nine-year-old fund that’s earned a Great Owl designation for consistently excellent risk-adjusted returns. Leuthold Core LCORX -10.2 5.8 Leuthold is a tactical allocation fund, driven by rigorous quantitative analysis, that can invest in virtually anything (pallets of palladium, anyone?). Morningstar lists it at 28% cash. An active ETF version is pending. Queens Road Small Cap Value QRSVX -9.7 5.4 Another small cap value fund with a distinguished management team and substantial cash, about 16%. Intrepid Endurance ICMAX -6.1 0.0 Endurance, a small cap fund, holds 45% cash. Its brilliant long-term record has been threatened by the departure of managers Eric Cinnamond (2010) and Jayme Wiggins (2018). Pinnacle Value PVFIX -13.9 -0.5 Like Endurance, this is a small cap fund; more properly, a microcap value fund. It’s at about 38% cash. Palm Valley Capital PVCMX n/a n/a Former Intrepid managers Cinnamond and Wiggins have struck out on their own to create a new absolute value small cap portfolio. As of June, their new fund was still 90% cash and they were caustically skeptical about the state of the small cap market, and willing to wait for it to pop. In the cases where we don’t have a profile of the fund, we’ve written about them in other articles and have profiles now in-process.

Of these funds, FPA and Leuthold have the broadest go-anywhere mandates, while Castle has the broadest discretion within the realm of equity investing.

Strategy Three: Embrace complexity

This strategy suggests that you choose a fund where the manager is willing to vary their exposure to the equity market either by choosing to bet against individual stocks or stock sectors, a process called “shorting,” or by buying a sort of short-term insurance policy that pays off if a stock falls or volatility spikes, a process called “buying or selling options.” Upside: long/short managers can play offense as well as defense; that is, they can use their short positions to try to drive up returns during good markets while simultaneously hedging risk. Downside: these are complex strategies, and complex things (1) have a tendency to break, (2) are hard to operate and (3) cost a lot. The best advice we have in approaching long/short funds is to make sure you understand exactly what the manager is doing and you choose managers who are not still using training wheels. Whenever markets begin to fall, long/short “specialists” come out of the woodwork and, on whole, we’d rather they get their on-the-job training with someone else’s money. The folks below have been running these strategies, and running them well, for a long time.

Here’s the three-year snapshot for the long-short equity funds that MFO has commended to your attention.

Maximum loss

Annualized return

Notes

-12.4

12.9

The best performing long-short fund in existence over the past three years, it plays offense rather more than defense, targeting bad companies in dying industries.

LS Opportunity LSOFX

-8.0

8.5

LSOFX has an absolutely first-rate management team from Prospector Capital which also offers a long-only fund using the same strategy. The only fund on this list, and one of the few anywhere, whose worst three-year rolling period is still positive.

-9.4

7.1

Managers Moran and Johnson embrace Benjamin Graham’s argument that “The essence of investment management is the management of risks, not the management of returns.”

-8.7

0.1

Not technically a long-short fund, but close enough for our purposes. It’s a top tier market neutral fund in about three years out of four.

-7.9

-0.9

Otter Creek is a solid fund that missed out on its peer group’s substantial gains in 2017. The negative three-year return is driven by 2017; despite a “value” investing style, which is out-of-favor, the fund is much more frequently atop its peer group than behind it.

Invenomic BIVIX

n/a

n/a

Intriguing newcomer that roared out of the box, hard-core value investing had a really bad summer 2019. The manager has solid credentials as a former Boston Partners guy and a clear strategy for using his short portfolio to add alpha, not just buffer risk.

Bottom Line

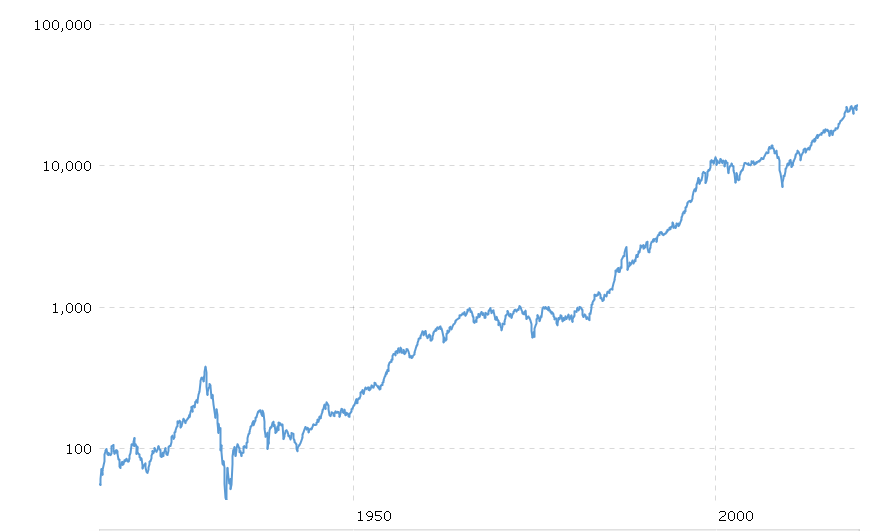

What should you do in the face of scary markets and howling headlines? That depends, in part, upon your age. If you’re 25 or 35 and looking at decades against in the market, check the chart below, roll your eyes, stick with your long-term plan and go enjoy that risotto.

100 years in the US stock market. Source: https://www.macrotrends.net/1319/dow-jones-100-year-historical-chart

If you’re 40, 50 or 60, majors declines are a bit more consequential and a lot more stressful. You might find a noticeable hedge in your portfolio useful and reassuring. If successful long-term investors like Mr. Romick or the folks at Leuthold are sitting near 30% cash, that might be a signal to consider a tactical move in that direction.

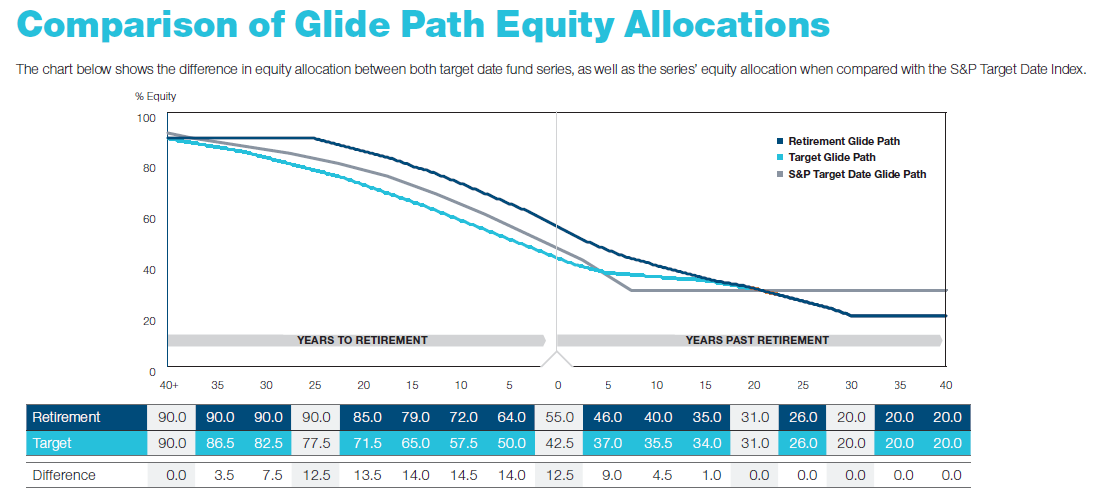

If, like me, you’re over 60, it might be more a matter of reflecting on your strategic, long-term allocation than fretting with a short-term tactical allocation switch. Many of us drift along, not adjusting our portfolios to our changed life circumstances. If that’s you, you might look at the glidepath for T. Rowe Price’s excellent Retirement target-date funds to see whether you’re still in a rational, defensible spot.

T. Rowe offers two sets of target-date retirement funds, each of which becomes more conservative as the fund’s target-date approaches. If you planned on retiring in 15 years, you might reasonably choose Retirement 2035 if you’re aggressive or Target 2035 if you’re a bit conservative. One way to test the positioning of your portfolio is to guess how many years it will be until you retire or, alternately, note how many years it’s been since you retired. You can use the chart above to get a prudent range for the typical investor’s stock exposure.

Thirteen years to retirement? Cool! You might choose either a 2030 fund (11 years out) or a 2035 fund (16 years out) and, with either of those, you might choose the more aggressive Retirement or the more conservative Target fund. The chart above implies that the most aggressive you would be is 79% equity (Retirement 2035) and the least aggressive would be 58% (Target 2030). While that’s still a fair range of values, it does imply a bounded set of choices: most aggressive (79%), moderately aggressive (65-72%) or less aggressive (57.5%). Find the spot that you (your family and your advisor) are comfortable with, then stick to it.

MFO Premium membership is available as a thank-you from us for a tax-deductible contribution of $100 or more. MFO Premium members should surely investigate Charles’s new portfolio-level risk assessment tool.

-