But, it is, in general, the best place to begin the search for the answer. Optimists, who assume things will work out, tend to see more paths forward, more options worth considering, than pessimists (often dubbing themselves “realists”) who know that it’s eternally time to duck-and-cover.

The word “optimism” entered the English language (1759, in French 1737) several generations before pessimism (1794) did.

The psychological research on the effects of optimism is stunning. The champion of such research is Dr. Martin E.P. Seligman, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and Director of their Positive Psychology Center. His focuses on notions like “learned helplessness” and has racked up rather more than 325 journal articles and books. His most widely-cited work, Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life (Vintage Books, 2006) has been cited by other scholars on 7,998 occasions. In it he argues:

The defining characteristic of pessimists is that they tend to believe bad events will last a long time, will undermine everything they do, and are their own fault. The optimists, who are confronted with the same hard knocks of this world, think about misfortune in the opposite way. They tend to believe that defeat is just a temporary setback, that its causes are confined to this one case. Optimists believe that defeat is not their own fault: Circumstances, bad luck, or other people brought it about. Such people are unfazed by defeat. Confronted by a bad situation, they perceive it as a challenge and try harder.

These two habits of thinking about causes have consequences. Literally hundreds of studies show that pessimists give up more easily and get depressed more often. These experiments also show that optimists do much better in school and college, at work and on the playing field. They regularly exceed the predictions of aptitude tests. When optimists run for office, they are more apt to be elected than pessimists are. Their health is unusually good. They age well, much freer than most of us from the usual physical ills of middle age. Evidence suggests they may even live longer.

There are important parallels here to “the placebo effect.” For a long time, medical researchers considered the placebo effect to be a nuisance and a sign of failure; that is, if taking “a sugar pill” was about as useful as taking an experimental drug, they concluded that the drug was a failure. Newer research, embodied at Harvard’s Program in Placebo Studies, reaches the opposite – and more optimistic – interpretation: it’s not that the drug failed, it’s that the placebo worked. Our minds are able to have powerful effects on our bodies which aren’t limited to the rainbows-and-unicorns fluff associated with Pollyanna. We can will physiological changes into existence if we believe that those changes are due.

Vox published a nice summary of the placebo research, Brian Resnick’s “The Weird Power of the Placebo Effect, Explained,” in 2017. There’s a conspiracy afoot to trick you into getting smarter; it involves a number of smart people making learning seem fascinating and whimsical. They came together on the Christmas Eve edition of the Make Me Smart podcast in which Kai and Molly reprise an interview with Adam Conover, of the Adam Ruins Everything TruTV show. Conover is both a comedian and a really smart guy who tries to bring serious research comically to bear on various cultural myths and misunderstandings. Kai and Molly’s piece ends with a nice reflection by Adam on the power of placebos.

Why does it matter?

Good question! It matters because the world feeds your impulse toward pessimism and starves the prospects for optimism. Still, in ways small and large, there’s an objective case for optimism.

Many of us know the tragic story of the death of Mollie Tibbetts, an Iowa college student murdered in July 2018 by a young man who’d worked quietly in town for years, but who also was in the US illegally. His arrest in August led to threats against other migrant workers in Iowa, many of whom left in fear. Fewer of us know that Ms. Tibbetts’ mother took in the child of a migrant family that had fled; Ulises Felix had grown up in town, was a high school senior intent on graduating and faced the prospect of spending a year alone in the one still-furnished room of a trailer home. At her son’s behest, she invited Ulises to live in their spare bedroom. It was a quiet gesture without great political significance, but also an important and good one.

Many of us know that greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere continue to rise, which raises the prospect of catastrophe. Fewer have reason to note the dozen or so global trends, social and environmental, that reflect the fact that many people are working passionately to make the world a better place. Elijah Wolfson, writing for Quartz, detailed How the world got better in 2018, in 15 charts.

The Gates Foundation’s 2018 “Year in Review” report similarly detailed the many things that are going right in the world. Some are huge (a billion people were vaccinated in tropical countries), many were small (toilet tech improved) and all were threatened by pessimism. Sue Desmond-Hellmann, the president of the Gates Foundation warned, “the biggest threat is a sense of despair and pessimism … youth who feel like they don’t have an opportunity to have a better life … to have a happy, productive, fulfilled life and to achieve something. That’s the biggest threat.”

Traditional media has always followed the maxim, “if it bleeds, it leads.” Editors and publishers know that we’re transfixed by horror (Stephen King has sold over 350,000,000 copies of his horrifying stories), so they feed it to us. Social media, an addictive vortex of horrifying fiction posing as secret truths, makes fear and loathing into virtues.

The markets likewise: the five FAANG stocks lost a trillion dollars this fall, the US markets evaporated a trillion in value in a single week, the Chinese market misplaced nearly $3 trillion this year, global markets vaporized $3 trillion in just two days … and worse, worse, worse! is yet to come.

Or not.

Stock market valuations, the key driver of future investment returns, are historically high but becoming more reasonable daily. Interest rates, the key driver of corporate capital decisions and income-investor returns, are low but becoming more nearly normal. Volatility, a key tool for restraining irrational exuberance and investment bubbles, has become a top-of-mind phenomenon.

To be clear: those are all good things as long as we’re willing to make them into good things.

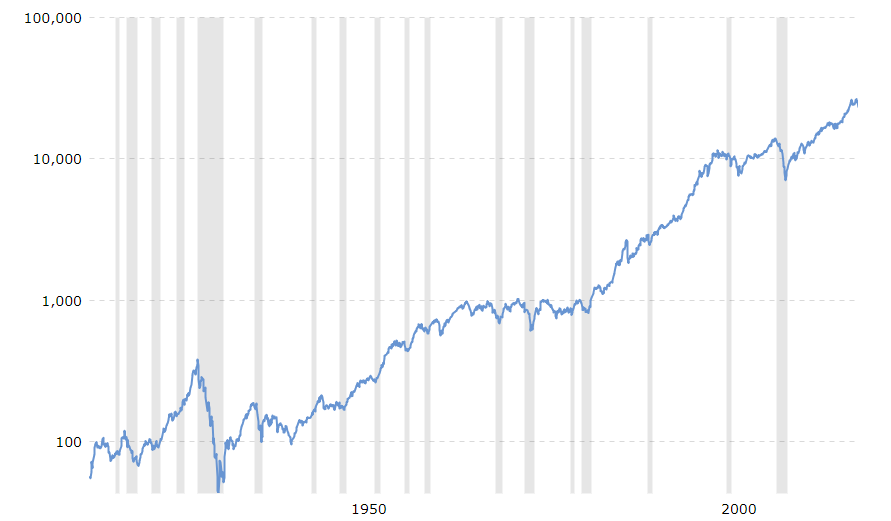

For investors in their 20s-40s: you’ve been blessed with a series of incomparable gifts. You’re young. (We forgive you.) The current repricing of the markets is utterly inconsequential to your long-term gains. Here’s the Dow Jones average over the past 100 years on a “log scale” so that a 1% gain in 1920 (a rise of less than one point in the DJIA) is the same as a 1% gain in 2010 (which would require a rise of over 100 points). The 18 gray bars are economic downturns.

In general, pick any point in the past century, move 25 years forward and look up – generally way up – at the new value of your portfolio. Unless you have reason to anticipate a return to the Dark Ages, the current thrashing about is precisely as important to your long-term prospects as the frenzied yapping of a small dog.

You’ve got access to more investing tools, more affordably priced, than any generation in history. Asset valuations are slowly returning toward rational levels (umm, not there yet but …) and rising interest rates should impose some discipline on the stock market (it’s harder to borrow more to do silly things when the money’s a bit expensive). There are, in particular, a number of really well-designed multi-asset funds – from target-date funds to “income builder” strategies – that come awfully close to fire-and-forget investments.

For investors in the latter stages of their careers: the current noise is precisely as consequential as you allow it to be. Your returns and volatility are driven more by the asset allocation you’ve chosen than by the individual investments – active or passive, ETF or fund, boutique or behemoth – you’ve selected to implement that allocation.

The mantra “stocks for the long-term” is double-edged. First, stocks are your portfolio’s best friend over the next quarter century and its worst enemy over any “next decade.” Stocks are highly volatile, seductive during their long, relentless “it really is different this time” bull runs and destructive in the inevitable aftermath if you haven’t planned for profiting from the price collapse.

Here’s the magnitude of the losses you might face. I searched MFO Premium’s database for the five largest equity funds, balanced funds and bond funds then pulled up their maximum drawdowns (i.e., largest-ever declines) and how long it took them to get back to break even. It turns out that all of the largest equity funds are passive, four Vanguard index funds and a State Street ETF that hold two trillion in assets, so I added a separate line for the largest actively-managed equity funds (four American and one Fidelity).

| Class | Drawdown, in percent | Recovery, in months |

| Equity, passive | 52 | Five years, six months |

| Equity, active | 47 | Five years, one month |

| Balanced | 34 | Three years |

| Bond | 11 | One year, nine months |

With both the pure equity and pure bond lines, one of the top five funds was a significant outlier which a much longer drawdown and much slower recovery than the others, so your results might be a little better.

Here’s the translation: if you own an equity fund, you might reasonably anticipate losing half of your investment at some point. If you don’t sell in a panic, but also don’t deploy your “dry powder” during the worst of the bear, you will not break even for five long years; a bit more for index funds, a bit less for active ones. Those aren’t worst-case numbers, those are the performances of the largest funds which got to be large by being abnormally steady. The worst case numbers, among funds with $10 billion or more in assets:

| Class | Drawdown, in percent | Recovery, in months |

| Equity, passive | Invesco QQQ Trust, 81.1% | State Street Technology Select Sector SPDR, 17 years, 10 months |

| Equity, active | Janus Henderson Enterprise, 77% | Janus Henderson Enterprise, 14 years, nine months |

| Balanced | Fidelity Freedom 2050, -52.7% | First Eagle Global, six years, three months. |

| Bond | Nuveen High Yield Muni Bond, 44.2% | Vanguard Long-Term Tax-Exempt, five years, two months. |

(Still not the worst-case; remember this screen only examines the performance of very large funds. For complete details, folks who are members of MFO Premium can screen the records of 17,000 funds, ETFs, CEFs and insurance products to see how they compare over any of dozens of different time periods.)

We have argued, and will continue to argue, that the Cult of Equity is overblown. For most folks over 40, a smaller stock allocation than you might imagine will serve you best, especially in your non-retirement portfolio.

For the managers of active mutual funds: the day you’ve been praying for has come! It’s no longer the up-and-away market that favors whoever offers the purest equity exposure all the time at the lowest cost. The arguments for active management are that (1) managers have the flexibility – through holding cash or dodging the priciest issues – to moderate the effects of a downturn and position investors for a rebound and (2) managers can communicate clearly and frequently, allowing their investors to avoid the worst of their impulses. It’s time to put up or shut up.

For the advocates of liquid-alt strategies: likewise. The average 60/40 balanced fund, for which liquid alts often claim themselves a successor, dropped 9.3% during the last three months of 2018. Every single liquid alts category outperformed that, with market neutral funds clocking in a -0.6%. The rub is that no category of alts earned as much as 3% annually over the past three years. The excuse has been “hostile market conditions,” with zero interest rates and a massive tax cut underwriting all sorts of excess. That’s past now. It’s time to step up, or step aside.

Bottom line. Here’s what I know about 2019: it will be 365 days long. Pretty much everything beyond that is conjecture.

Here’s what I conjecture: it will be a year of great adventures, in the markets and otherwise. It is likely to be marked by great volatility, in the markets and otherwise. Folks who want to sleep well at night they might reasonably act on the recommendations of Vanguard founder Jack Bogle:

Trees don’t grow to the sky, and I see clouds on the horizon. I don’t know if and when they’ll arrive. A little extra caution should be the watchword. If you were comfortable at a 70 percent to 30 percent [allocation of stocks to bonds], under these circumstances you’d like to go back to 60 percent to 40 percent, or something like that.

The Observer’s special passion is for investors with exceptional risk management disciplines and records. We will continue to highlight for you the folks with the wherewithal to keep you safe and to invest responsibly beside you. Seek them out.

Having done that, you might reasonably turn to Warren Buffett’s recent recommendation:

The one easy way to become worth 50 percent more than you are now — at least — is to hone your communication skills — both written and verbal. If you can’t communicate, it’s like winking at a girl in the dark — nothing happens. You can have all the brainpower in the world, but you have to be able to transmit it.