It’s sensible to think, in advance, about the best responses to a market that is expensive, increasingly volatile and beset by external shocks, from tariffs to rising interest rates and policy instability.

An unauthored piece in ETF Trends recently weighed in with this advice: look at buying inverse or levered inverse ETFs.

With the heightened uncertainties gripping the markets, investors may look to inverse or short stock ETF strategies to hedge potential risks ahead … investors can hedge against dips in the Nasdaq through bearish plays. For instance, the ProShares Short QQQ ETF (PSQ) takes the inverse or -100% daily performance of the Nasdaq-100 Index. For the aggressive trader, the ProShares UltraShort QQQ ETF (QID) tracks the double inverse or -200% performance of the Nasdaq-100, and the ProShares UltraPro Short QQQ ETF (SQQQ) reflects the triple inverse or -300% of the Nasdaq-100. (10 inverse ETFs to hedge against further stock market risks)

We couldn’t reach internal agreement on how best to respond, so instead here are four equally valid responses from MFO insiders.

In a word: no.

In two words: not ever.

In three: are you kidding?

In New Jersey: fuhgedaboudit!

Inverse funds and ETFs are not buy-and-hold investments; they were created for the benefit of traders whose holding period might be measured in minutes. Most, which target the inverse of an index’s daily movement, are designed to be held in portfolios which are adjusted daily. ProShares, with a suite of inverse and leveraged funds, warns you, “Investors should monitor holdings as frequently as daily.” Rydex, one of the first firms to target this slice of the market, flags the special risk of leveraged funds: “The effect of leverage on a Fund will generally cause the Fund’s performance to not match the performance of the Fund’s benchmark over a period of time greater than one day.” Rydex competitor Direxion, which offers highly leveraged inverse ETFs among its suite of products, notes: “The funds should not be expected to provide three times or negative three times the return of the benchmark’s cumulative return for periods greater than a day.”

In March 2018, Vanguard’s Emerging Markets ETF (VWO) declined by 0.22%. If you’d had the wisdom to hedge your portfolio by buying Direxion Daily MSCI Emerging Markets Bear 3X Shares (EDZ), which rise by three times the daily fall of the emerging markets, what would your monthly return have been?

- I lost 0.66%

- I gained 0.66%

- I gained 6.66% (I’m such a devil)

- I lost 3.66%.

The correct answer is “4.” The market lost money, but your hedge lost 18 times as much money. If you’d bought the same hedge on January 1st, your year-to-date return would up about 6% while the EM ETF fell three. Nice, you made money but … you did not make three times the loss of the index and, more importantly, your fund would have risen by double digit amounts in two of the first seven months of the year and would have fallen by double digit amounts in two of the first seven months.

The likelihood of catastrophic failure with such funds is greatest just when you need them the most. Morningstar’s Paul Justice reviewed a whole series of studies of the performance of leveraged inverse ETFs during the 2007-2008 market crisis and concluded they were mostly tools for multiplying your losses. “Leveraged and inverse ETFs,” he warned, “kill portfolios.”

Bottom line: avoid these unless you’re a sophisticated trader whose life has been entirely surrendered to the constant, hypnotic pulsing of red and green movement trackers.

For the rest of us, the best move starts by asking whether you’re comfortable with the prospect of losing 15 t0 50 per cent? If not, consider two strategies for reducing your downside. First, invest some or all of your portfolio with managers who aren’t afraid to hold cash when the markets are high and deploy cash when the markets are crashing. Such folks (Aegis, Cook & Bynum, FMI, FPA, Intrepid, Provident Trust, Tilson and others) typically look worst just before a market peaks.

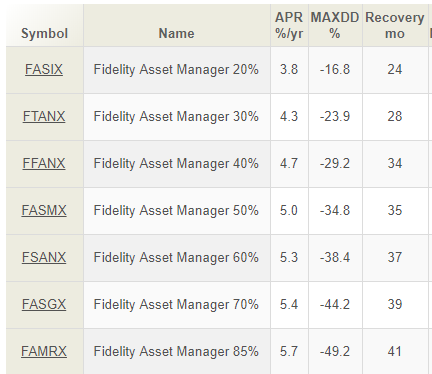

Second, consider reducing your equity exposure. Your returns are effected by your portfolio’s exposure to equities, more than by any other factor. Greater equity exposure can increase your returns by a percent or two annually (which is important if you’re thinking in terms of decades) but will also vastly increase your losses in a bear market (which is important if you’re thinking in terms shorter than decades). The performance over the current market cycle (October 2007-present) of Fidelity’s Asset Manager series offers a preview of the effect of asset allocation on portfolio risk. The funds have the same managers, comparable expenses, and own the same equities, just in different proportions. Here’s the picture:

So, a portfolio with 20% equities has returned 3.8% annually. It suffered a 16.8% decline in the worst of the market crash, and took 24 months to recover from the decline. A portfolio that was almost fully invested in stocks, FAMRX, has returned 2% more annually … but suffered a loss three times as great and took almost a year-and-a-half longer to recover.

Choose well!