The most consistently strong analyses of US and world markets come from a shrinking handful of sources, The Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal prominent among them. MFO maintains a paid subscription to each.

Nonetheless, even they produce the occasional bewildering piece. In “If you want to do good, expect to do badly” (6/29/2018), the Journal’s James Mackintosh revives an old canard. “Investors are increasingly convinced that they can buy companies that behave better than the rest and make just as much money. They are wrong.”

It’s an argument in two parts: (1) there’s no uniform agreement on what values to screen for and (2) even spectacularly evil corporations, if such things exist, can make tons of money.

That strikes me as interesting but irrelevant. The fact that there are different ways to define “responsible behavior” does not mean that portfolios seeking responsible corporations, variously defined, will underperform. And the fact that bad guys can make money does not impair the ability of good guys to make at least as much.

Virtually all academic research agrees with us. There have been over 2000 studies in developed and developing markets which have examined this very question. Some studies find in one direction, some in the other but when scholars begin screening out poorly designed studies and combining the data from the remainder, they tend to support ESG investing.

|

Technically we refer to the procedure of identifying, vetting and combining as a meta-analysis. The procedure used in many disciplines to increase the clarity of results by treating many small, well-designed experiments as if they were part of one large, well-designed experiment. An introduction to meta-analysis published in the medical journal Hippokratia notes “Outcomes from a meta-analysis may include a more precise estimate of the effect of treatment or risk factor for disease, or other outcomes, than any individual study contributing to the pooled analysis …The benefits of meta-analysis include a consolidated and quantitative review of a large, and often complex, sometimes apparently conflicting, body of literature.” (A.B. Haidich, “Meta-analysis in medical research,” 12/2010). If you’re interested but not so geeky, there’s also a Wikipedia entry on the topic. |

So here’s the evidence from a review of over 2000 published academic studies:

The search for a relation between environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria and corporate financial performance (CFP) can be traced back to the beginning of the 1970s. Scholars and investors have published more than 2000 empirical studies and several review studies on this relation since then. The largest previous review study analyzes just a fraction of existing primary studies, making findings difficult to generalize. Thus, knowledge on the financial effects of ESG criteria remains fragmented. To overcome this shortcoming, this study extracts all provided primary and secondary data of previous academic review studies. Through doing this, the study combines the findings of about 2200 individual studies. Hence, this study is by far the most exhaustive overview of academic research on this topic and allows for generalizable statements. The results show that the business case for ESG investing is empirically very well founded. Roughly 90% of studies find a nonnegative ESG–CFP relation. More importantly, the large majority of studies reports positive findings. We highlight that the positive ESG impact on CFP appears stable over time. Promising results are obtained when differentiating for portfolio and nonportfolio studies, regions, and young asset classes for ESG investing such as emerging markets, corporate bonds, and green real estate. (Friede, Busch and Bassen, “ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies,” Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, 2015)

Okay let’s review the highlights of that long paragraph:

- It’s based on 2200 published studies

- It’s the most exhaustive review ever

- 90% of those studies find a “non-negative relation,” that is, 90% say you lose nothing by ESG investing

- A “large majority” say it’s a net gain for your portfolio, and,

- It’s true across across time periods, markets and asset classes. It’s even true for “young” asset classes such as emerging markets and green real estate.

More recent studies corroborate those sorts of findings. A 2018 study of emerging markets found “significant outperformance based on ESG integration” into the portfolio (Sherwood & Pollard, “The risk-adjusted return potential of integrating ESG strategies into emerging markets equities,” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, “2018) and another 2018 study of low-carbon portfolios found that they “typically earns a slightly higher rate of return than the overall market” (Halcoussis & Lowenberg, “The effects of the fossil fuel divestment campaign on stock returns,” North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 2018).

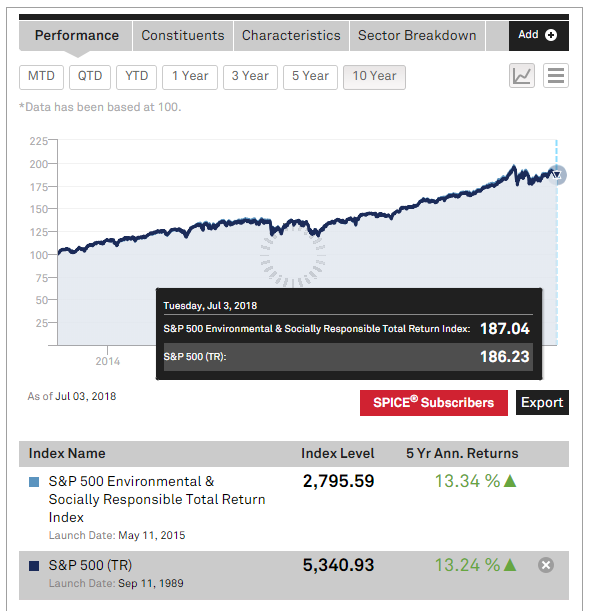

ESG-screened indexes slightly outperform their unscreened versions. Here, for example, is a decade-long comparison of the S&P 500 and its ESG-screened sub-set.

Standard & Poor’s formally launched their ESG screened index in 2015, so older results were obtained by applying their screening criteria retroactively. It’s a form of data-mining and it can be misused, especially by marketers. For now, I’ll give Standard & Poor’s the benefit of the doubt and assume they didn’t consciously rig the results. Assuming that, over both five- and ten-year periods, the S&P ESG modestly outperformed the S&P 500.

Morningstar makes the same point about fossil fuel free portfolios. Jeremy Grantham, in a June 2018 keynote address at the Morningstar conference, makes the argument – and makes it well – that we’re in a race for our lives. The confluence of global warming, with its attendant rise in extreme weather and fall in agricultural productivity, and African population rise may, sooner rather than later, rip apart the comfortable existence enjoyed by many of us in the Northern Hemisphere. He doesn’t believe that investors, on their own, can make enough impact to save us … but he does believe that we should take all of the steps available to us, including a switch to fossil fuel free portfolios.

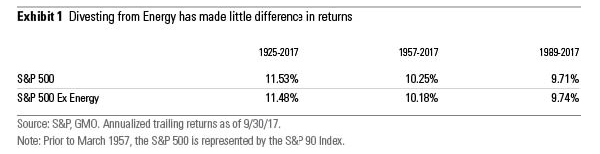

Morningstar looked at the investment consequences of such a switch, and found that the downside – if any – was negligible.

In the worst case, investors lost 5 basis points. Since the rise of tech is a global driver, investors would have gained 3 basis points by avoiding the energy sector.

That difference might rise: as more and more investors value responsible corporations, such stocks are likely to see an emergent price premium.

It is entirely possible to produce terrible results in an ESG-screened fund. Some ESG-screened funds suck. They’re expensive. They’re undisciplined. They’re run by clueless opportunists looking to ride a marketing wave. They’re execrable.

Got it.

But they’re not execrable because they’re ESG-screened. They’re execrable because they’re plagued by a dozen other problems. The same can be said for every other category of fund.

Bottom line: Here is MFO’s recommendation: don’t buy crappy funds. Look for managers who have a long record of getting it right, who communicate clearly and forthrightly, whose interests (read: money) are aligned with yours, whose fees are reasonable given the services provided and who have strong risk-management disciplines.

Mr. Macintosh’s article ends where, I think, is should have begun: “For some of the world’s biggest, most long-term investors, the true aim is to avoid risks that could break capitalism, whether because of social or environmental catastrophe. [Quoting the manager of Japan’s $1.5 trillion pension fund] ‘we need to avoid systemic failure of the capital markets.’”

Global catastrophe is not in your best interests, nor in your children’s nor in your portfolio’s. The seeds of such a catastrophe were planted more than a century ago and it is, bit by bit, coming upon us today. You may choose, as many have done, to pretend in the face of overwhelming evidence that it is otherwise. We baby boomers will pass, soon enough, from this earth. I wonder if we will, soon enough, be reviled as “the generation that just stood and let it happen”?