Quaker Funds, based in Berwyn PA, are a small family at tactical allocation funds. As they imagine a transition which will include an ESG focus, it became clear that Thomas Kirchner’s event-driven fund would be something of an anomaly. Event arbitrage funds aim to profit from predictable but short-lived market anomalies when, for example, a firm announces a change of control or reorganization. Limiting himself to relatively rare events in a relatively limited slice of the equity universe makes very little sense, so QEAAX/QEAIX is trying to join the Camelot fund family.

But that’s been delayed because the fund’s shareholders won’t open – or answer – their mail. The move to Camelot requires shareholder approval with at least 50.1% of shareholders voting yea or nay. After months of effort, only 41% of shareholders had weighed in. Why? One obstacle is investor privacy safeguards; when you click the “don’t allow third parties to contact me” option on your account set-up, you make it impossible for proxy solicitors to find you. Another obstacle is the fear of scams: during one recent contact attempt, a young voice shouted out from the background, “it’s a scam, mom! Don’t tell them anything, hang up!” And, as ever, people are lazy: we delete emails and trash paper mail, rather than going to the trouble to respond.

But that’s been delayed because the fund’s shareholders won’t open – or answer – their mail. The move to Camelot requires shareholder approval with at least 50.1% of shareholders voting yea or nay. After months of effort, only 41% of shareholders had weighed in. Why? One obstacle is investor privacy safeguards; when you click the “don’t allow third parties to contact me” option on your account set-up, you make it impossible for proxy solicitors to find you. Another obstacle is the fear of scams: during one recent contact attempt, a young voice shouted out from the background, “it’s a scam, mom! Don’t tell them anything, hang up!” And, as ever, people are lazy: we delete emails and trash paper mail, rather than going to the trouble to respond.

Here’s a plea from the fund’s managers: vote! (Please.) The solicitation process is expensive and is delaying what they believe to be an essential step for the fund.

Apparently Morningstar endorses the move. Their website has already renamed the fund, despite the fact that the vote hasn’t yet closed.

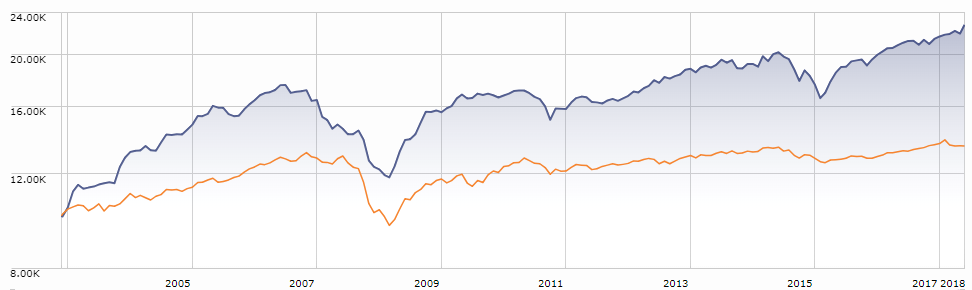

QEAAX is rated by Morningstar as a four-star fund. It began life in November 2003 as Pennsylvania Avenue Event-Driven (PAEDX) then, in June 2010, became Quaker Event Arbitrage (QEAAX) as part of Mr. Kirchner’s attempt to broaden the fund’s investor base. The fund (blue line) has handily outperformed its Morningstar peer group over its lifetime.

Bottom line: if you’re associated with the fund and haven’t voted, please do so. The same goes for shareholders of T. Rowe Price funds who, likewise, have been receiving proxy notices in the mail this month.

|

The most famous struggle for proxy votes may have been with the Steadman funds. Charles Steadman was in the running for the worst investor in history. Steadman took over the family’s investment business in the 1960s and began focusing on growth areas like ocean bed mining and undersea communities. (He’d have been so into bitcoin.) He lost money with breathtaking consistency, then died. His daughter ran the four funds, renamed them “Ameritor” then passed them over to Steadman’s long-time treasurer. Chuck Jaffe picked up the narrative: “When Charles Steadman died in the late 1990s, his daughter took over. The funds had no prospect for growth, but she had no reason to shut them; the double-digit management fee was like a personal annuity, up to the point where it bled the fund to death. When the Securities and Exchange Commission finally filed paperwork stating that the fund ‘had ceased to be an investment,’ the loss over the last 10 years was 98.98 percent, turning a $10,000 investment into $102. It took about four decades for the losses to drive shares down to less than a penny, but Ameritor got the job done, and then kicked the bucket.” 98.98% losses. NAV under $0.01. Why weren’t they liquidated decades before? In part because the shareholders were either dead or in denial about ever having invested with Steadman. The Baltimore Sun estimated that 40% of the firm’s accounts were legally “abandoned” and their final manager lamented that so many of the shareholders were dead that he couldn’t generate the quorum necessary to liquidate them. If you want a real rush of schadenfreude, you should read Jack El Hai’s “The Dead Man Fund,” a 2017 history of the decline and decline and decline and fall of the House of Steadman. It’s a quick read, ironically hosted by the site Longreads.com. |