This profile is no longer valid and remains purely for historical reasons. The fund has a new manager and a new strategy.

Objective

The fund seeks “maximum total return” through a combination of capital appreciation and income. The fund invests in undervalued securities, mostly mid- to large-cap dividend paying stocks. The manager has the option of investing in REITs, master limited partnerships, royalty trusts, preferred shares, convertibles, bonds and cash. The manager invests in companies “that he understands well.” The manager also generates income by selling covered calls on some of his stocks. As of February 28, 2018, the fund held 21 different investments, which included 15 common stock positions, three covered calls, and three closed end funds. Cash was just over 60% of the fund’s AUM at the end of 2017, and is down a bit by mid-2018.

Adviser

Centaur Capital Partners, L.P., headquartered in Southlake, TX, has been the investment advisor for the fund since September 3, 2013. The fund was originally launched as the Tilson Dividend Fund in March 2005. Until September 2013, T2 Partners provided branding and marketing for the fund in its role as advisor and Centaur Capital managed the portfolio investments in its role as the sub-advisor to the fund. When T2 Partners closed its mutual fund advisory business in 2013, Centaur Capital became the advisor to the fund and changed the name to the Centaur Total Return Fund. Centaur is a three person shop with about $100 million in AUM. It also advises the Centaur Value Fund LP.

Manager

Zeke Ashton, founder, managing partner, and a portfolio manager of Centaur Capital Partners L.P., has managed the fund since inception. Before founding Centaur in 2002, he spent three years working for The Motley Fool where he developed and produced investing seminars, subscription investing newsletters and stock research reports in addition to writing online investing articles. He graduated from Austin College, a good liberal arts college, in 1995 with degrees in Economics and German.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

Mr. Ashton has over $1,000,000 invested in the fund. The fund’s two trustees both have a modest investment in it.

Strategy capacity

That’s dependent on market conditions. Mr. Ashton speculates that he could have quickly and profitably deployed $25 billion in March, 2009.

Opening date

March 16, 2005

Minimum investment

$1,500 for regular and tax-advantaged accounts, reduced to $1000 for accounts with an automatic investing plan.

Expense ratio

1.95% after waivers on an asset base of $25 million.

Comments

You’d think that a fund that had squashed the S&P 500 over the course of the current market cycle, and had done so with vastly less risk, would be swamped with potential investors. Indeed, you’d even hope so.

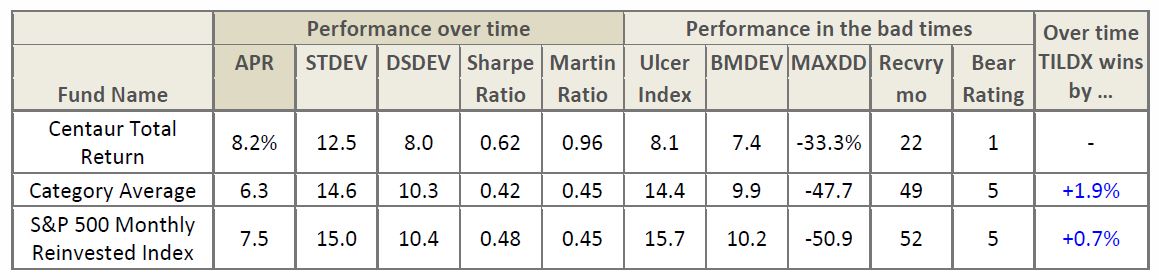

Comparison of Full Cycle 5 Performance (200711 – 201804, 126 months)

Here’s how to read that chart: over the course of the full market cycle that began in October 2007, Centaur has outperformed its peers and the S&P 500 by 1.9 and 0.7 percent annually, respectively. In normal times, it’s about 20% less volatile while in bear market months it’s about 25% less volatile. In the worst-case – the 2007-09 meltdown – it lost 34% less than the S&P and recovered 30 months sooner.

It’s impressive that Morningstar designates it as a five star fund, with a history of always being a four- or five-star fund. It’s more impressive that Morningstar’s new “machine learning” algorithm has awarded it a Silver analyst rating with “positive” scores for everything except price.

It’s exceptionally impressive that, over the course of the current market cycle, it’s one of the top four funds in its 86 fund Lipper peer group in pretty much every measure of risk and risk-adjusted performance: maximum drawdown (2nd), recovery period from its maximum drawdown (1st), Ulcer Index (2nd), Sharpe ratio (4th), Martin ratio (3rd), downside deviation (3rd), bear market deviation (3rd) and so on.

And you’d be disappointed. Centaur, with a spotless 13-year record, ranks 84th of 86 funds when measured by assets under management.

Centaur Total Return has evolved over time. It originally presented itself as an income-oriented equity fund, which is reflected in Lipper’s assignment to the Equity Income peer group. The argument for that orientation is simple: income stabilizes returns in bad times and adds to them in good. The manager imagines two sources of income: (1) dividends paid by the companies whose stock they own and (2) fees generated by selling covered calls on portfolio investments. Mr. Ashton reports that “the Fund’s strategy has become less income-oriented over time as our ability to sell covered calls for acceptable premiums has declined with lower market volatility over the years; in the last couple of years, we have purchased far more options than we’ve sold. Also, the number of stocks that meet our criteria for dividend securities has eroded due to the popularity of dividend-related strategies. As a result, the fund has become more capital gain oriented, though we try to position the portfolio to remain true to the underlying goals that we had hoped to achieve with the fund’s formative income-emphasis: lower volatility, better reliability, etc.”

The core of the portfolio is a limited number (currently about 15) of high quality stocks, supplemented by three closed-end funds and three covered calls. In bad markets, such stocks benefit from the dividend income – which helps support their share price – and from a sort of “flight to quality” effect, where investors prefer (and, to an extent, bid up) steady firms in preference to volatile ones. Almost all of those are domestic firms, though he’s had significant direct foreign exposure when market conditions permit. Mr. Ashton reports becoming “a bit less dogmatic” on valuations over time, but he remains one of the industry’s most disciplined managers.

The manager also sells covered calls on a portion of the portfolio. At base, he’s offering to sell a stock to another investor at a guaranteed price. “If Cisco hits $50 a share within the next six months, we’ll sell it to you at that price.” Investors buying those options pay a small upfront price, which generates income for the fund. As long as the agreed-to price is approximately the manager’s estimate of fair value, the fund doesn’t lose much upside (since they’d sell anyway) and gains a bit of income. The profitability of that strategy depends on market conditions; in a calm market, the manager might place only 0.5% of his assets in covered calls but, in volatile markets, it might be ten times as much.

Mr. Ashton brings a hedge fund manager’s ethos to this fund. That’s natural since he also runs a hedge fund in parallel to this. Long before he launched Centaur, he became convinced that a good hedge fund manager needs to have “an absolute value mentality,” in part because a fund’s decline hits the manager’s finances personally. The goal is to “avoid significant drawdowns which bring the prospect of catastrophic or permanent capital loss. That made so much sense. I asked myself, what if somebody tried to help the average investor out – took away the moments of deep fear and wild exuberance? They could engineer a relatively easy ride. And so I designed a fund for folks like my parents who can’t live on no-risk bonds but would be badly tempted to pull out of the stock market at the bottom. And so I decided to try to create a home for those people.”

And he’s done precisely that: a big part of his assets are from family and friends, people who know him and whose fates are visible to him almost daily.

Mr. Ashton has served his investors well, though in many ways they’ve served him – and themselves – poorly. Centaur’s excellence in both the 2007-09 and the 2009 rebound brought in droves of investors. As the market moved steadily from undervalued to fairly valued to overvalued, the number of securities meeting his quality and valuation criteria dwindled. When he found attractive opportunities, they rose in value too quickly to be long-term holdings. While he found some international names attractive, they couldn’t fill the portfolio. Cash now comprises 53% of his holdings. Unhappy with reasonable returns (13.5% in 2017, for example, which meant that the stock portion of the portfolio returned about 40%) and excellent risk management, investors have been steadily drifting away. Mr. Ashton is intensely aware of, and pained by, the consequences: a higher expense ratio and lower tax efficiency as he manages the outflows.

This profile is no longer valid and remains purely for historical reasons. The fund has a new manager and a new strategy.

Bottom Line

Mr. Ashton makes a fascinating point:

Stocks have been going mostly up for nine years now, and it feels like they will never – and maybe even can never – come back down. When thinking about it in the abstract (if they think about it at all) most people naturally believe that in times of stress that they will behave rationally, and that they won’t be among those who panic and sell at the worst possible time. The reality, of course, is that most investors aren’t so rational when the time comes, because when stocks are going down they feel like they might never go back up.

In short, the same psychological anchor that causes us to over-commit to stocks when they are riskiest (because they’ll never fall again) causes us to under-commit to stocks when they are safest (because they’ll never rise again). It takes an act of conscious discipline to invest today in ways that will serve to preserve your wealth, and your family’s prosperity, during the inevitable crisis. As the US market reaches historic highs and political rationality reaches record lows, that might be uncomfortably close. For folks looking to maintain their stock exposure, but cautiously, and be ready when richer opportunities present themselves, this is an awfully compelling little fund.

Fund website

Centaur Total Return Fund