“We live in an age of great events and little men.”

Winston S. Churchill

We have made it through another month, and another quarter. It was not quite so painless for either investors or money managers, as year to date the S&P 500 has now dropped into negative territory. Volatility is clearly back. And while active managers made a valiant effort during the last week of the quarter to move the averages back up into positive territory, it was not to be.

What comes next? Stocks are still overvalued by most measures. And bonds, given an upward trend in interest rates, with the Federal Reserve committed to more hikes, don’t offer a place to hide.

According to my friend Larry Jeddeloh at The Institutional Strategist, tech valuations look to be close to where they were in 2000 before the dot.com implosion, which was triggered by an absence of liquidity in the U.S. banking system. So once again we may get to see whether valuations and liquidity have an impact on technology businesses.

The question now arises as to how we pay the increased rates on our debt if the Fed keeps raising rates. (Per the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “if interest rates were 1 percentage point higher than expected, debt would rise by $1.7 trillion over ten years.”) The answer seems to be that we will look to inflate our way out of the increased interest payments.

Friend Jeddeloh has also opined that home prices are now back to about where they were, if not below where they were, just before the beginning of the Great Recession in 2008. Since many steps have been taken to keep the banking system from getting into trouble again, this time it looks like the onus has been put on the homeowner. Namely, as rates go up (which we have seen in mortgages), the prices of homes will have to come down for there to be a clearing of the excess inventory. Alternatively, people are going to be staying in their houses a lot longer, rather than being able to sell to afford the entry deposit to the retirement community.

In that vein, I have to say that I had more reaction to my column last month about condominium prices in Chicago over the last three years than I have had in response to almost any other column I have written. It turns out that price increases and sales have come not just to a halt in Chicago, but also in New York City and Boston. That lack of sales activity has been masked to some extent because the building trades and the manufacturers and suppliers of building materials have remained quite busy.

Why? One reason is the unusually large number of catastrophic storm, fire, and other losses homeowners have suffered across the country since last summer. We have had hurricanes and flooding in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico, along with storm damage all up the East Coast running from Florida up to Maine, and fires in California. The winter storms this year have added to the toll. So what? Well, the big homeowner’s insurance companies are first movers in that regard, as they endeavor to limit or mitigate further damage. What might have been normal building materials inventories for where we are in the real estate cycle, before the catastrophe losses, have been drawn down to effect repairs. And contractors and sub-contractors in the various trades are filling their order books with more work commitments than they can fulfill in the usual time. A person at one insurance agency that has clients at the high end of the business in those geographic areas told me, within the last two weeks, that no contractor she has been trying to hire for repair work will guarantee materials pricing out more than thirty days. And the head of personal lines at a major property and casualty company has confirmed for me that this year has started off as last year ended in terms of weather events.

And these issues are before we understand the full effect of tariffs. Last summer, the Trump Administration put a tariff on Canadian timber, which has impacted the pricing and availability of some categories of lumber. Given that we have had a long, cold winter in the northern tier of the country, it will probably also take longer for domestic loggers to get into the forests, cut new timber, and get it out and into the kilns to prepare for delivery. And that was before we have had the new wrinkle of tariffs on steel and aluminum. And to that add the uncertainty as to which countries and products those tariffs will ultimately apply (a Chicago architect mentioned to me last week that they were seeing a ripple through of pricing increases on steel in commercial projects on the order of 20%).

The Great Unintended (or Maybe Not) Consequence

The above provides fair warning that we are going to see conditions of extreme volatility in both new construction and repair work. There is one area that I don’t think people have considered. That is the changes in consumer thinking that will be driven by the new personal income tax changes.

There are some parts of the country which in effect have two-tier residential home markets. One tier is for those who live and work in that marketplace year-round, for whom it is home. The other tier in that market is the second home owner, who comes to the area on weekends and holidays as well as for extended periods of time during the year, either in the summer to enjoy the weather and access to water sports and boating among things, or in the winter for winter sports. Some of the obvious locations are Santa Fe, New Mexico; parts of Colorado and Montana, and much of the coastal areas of the East Coast. Two areas that I am familiar with that fall into that category are Litchfield County in northwest Connecticut and southern Berkshire County in western Massachusetts. For those locations, the second tier of homes are those whose market values/selling prices are usually greater than $750,000 and rising on up to the $2 or $3M range. Most people in that category of homeowner in those two counties come up from New York City, which is generally a two to three hour drive or drive plus train trip, to spend at least three weekends of every month in that second home.

What has changed? Well, the amount of subsidy by the Federal tax act has changed. State and local deductibility of taxes is now capped at $10,000 so deducting all your New York City property taxes and all your Massachusetts property taxes is gone. In fact, you will most likely be unable to deduct most of your New York State and City income taxes, and your property taxes in New York. The deductibility of first or second home mortgages above $750,000 is also gone. My sense is that when this year’s tax return is received and the estimates for the coming year are also received, there is going to be a very rude awakening. And to me that translates to the incremental demand coming from people looking for that kind of weekend property drying up, UNTIL the clearing prices of the existing inventory of those homes for sale above $750,000 comes down to where people think they are getting a real bargain.

There will be another tangential effect, detrimental to those second home communities. And that is that the boost to revenues they have gotten from increased property taxes in a rising price property market will be on hold, putting pressure on municipal budgets. They will have to cut services, raise the rate of property taxes, and add new fees on other services, or some combination of all three. On that cheerful note, I am going to end, as far as the meat of this letter is concerned.

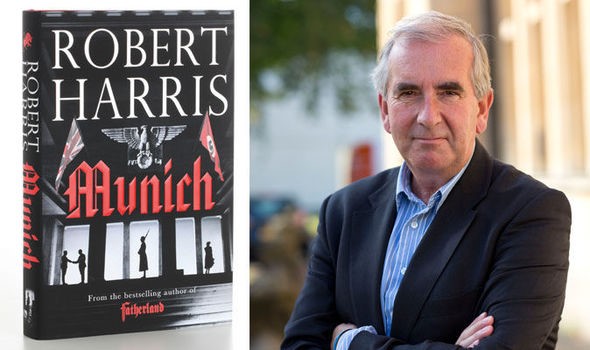

Every now and then, I read something, either fiction or non-fiction, that I feel is worth recommending. This time, my recommendation is Munich by Robert Harris, a work of fiction set around the meetings between Chamberlain and Hitler in 1938. Harris, who tends to write works of historic fiction that do a good job of catching the personalities and atmosphere of a place and time, here has managed to catch the feel of Great Britain, still reeling from the casualties in the Great War and Germany, seeking payback for the humiliation of Versailles. I think the following paragraph, an apocryphal conversation between two British diplomats on Chamberlain’s plane flying to Munich for the historic meeting captures things:

“I was with the PM in Bad Godesberg. We thought we had an agreement then, until Hitler suddenly came up with a new set of demands. It’s not like dealing with a normal head of government. He’s more like some barbarian chieftain out of a Germanic legend – Ermanaric, Theodoric – with his housecarls gathered around him. They leap up when he comes in and he freezes them with a look, asserts his authority, and then he settles down at a long table to feast with them, and to laugh and boast. Who’d want to be in the PM’s shoes, trying to negotiate with such a creature?”