“In wars then let our great objective be victory, not lengthy campaigns.”

Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Another year-end is in sight. Those of us who have been conservative in our asset allocations and predicting the end of the world have once again it seems, been proven wrong. Or perhaps not, for as the market keeps rising, the breadth keeps getting narrower. Or least it had been. It begs the question of whether we are setting up for a blow-off, heading straight up through year-end, or something else.

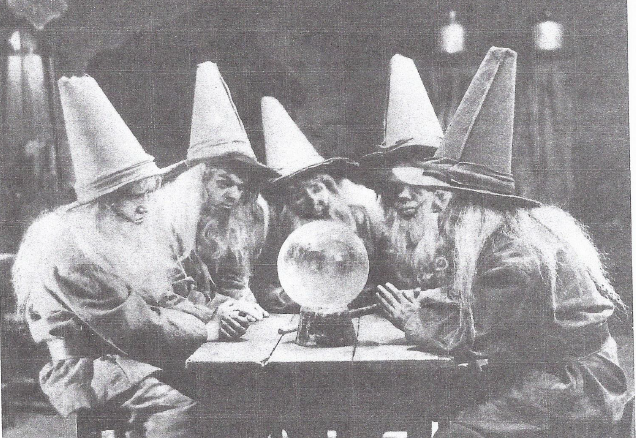

Attached is a picture of a group of active value managers in Chicago, which I think is indicative of the issues all value investors face at this point in time. Put simply, the valuation metrics make no sense.

A research analyst at one local firm, speaking with his peers at a coffee break at the recent Baird Industrial Conference, was asked how he could justify the issues in which investor money was being placed. His answer was that the lowest risk category of equity issues now had a discount rate of 6% being used in the dividend discount model. And as the person who related that narrative to me said, “Perhaps even 6% is too high at this point.”

What I know is that increasingly, institutional investors are more worried at this time of year about job security and missing or having missed the train as it has left the station, resulting in under investment.

That of course leads to performance which lags the benchmarks. So once again the index funds will look smarter (and certainly cheaper). But again the focus is not on how much can be lost. For those pondering this in their real life portfolios, I suggest you pay attention to the recovery period it takes for a fund to earn back from its point of maximum drawdown. All of that information is available to those making use of our premium site.

Swensen’s Thoughts

We have often spoken with admiration about David Swensen who runs the Yale Endowment. Two weeks ago he was a speaker at an annual Council of Foreign Relations program, the Stephen C. Freidheim Symposium on Global Economics, where he was interviewed by Robert Rubin, the former Treasury Secretary. I commend the whole event to you as it is available on YouTube. One of the points that resonated with me is that he has been engaged in a conversation with Yale’s Provost about the wisdom of reducing the assumed rate of nominal returns on the endowment portfolio from 8.25% down to 5%. We have heard a similar debate in other quarters about the need to reduce the assumed rate of return on pension funds, given where interest rates are (or are not). But if we reduce them to what makes both actuarial and financial sense, those pension plans are even more under-funded than they appear to be at present.

Swensen of course, is not a fan of the public markets, feeling that most active managers have become subject to too much short-termism in investing, focusing on quarterly earnings numbers. One of the points he makes is that finance classes in business schools spend too much time talking about normal distributions for stock returns. His point is that we know that those distributions are not normal, for if they were the Crash of 1987 representing a 25X standard deviation event could not have happened. His bias in the endowment is clearly for what he describes as “uncorrelated investments.” That is why the amount of the endowment that is in private equity is in excess of 30%. But the private equity investment firms he favors are those that invest in companies and make them better. This is not the private equity that takes a company private with cheap money, piles on leverage, strips the balance sheet, and then sells it to the greater fool, either another private equity flipper or by going public when there is an appetite for garbage.

He also does not like activist investors, His concern is that the activists take a position in a business, and then ask for cash back. And the cash can come in the form of a dividend, or the cash can come in the form of a share buyback. But he thinks there is a certain naivety that impacts the quality of a business, and as a result the quality of the markets.

Swensen prefers the hands-on operators in buy-out funds who want to improve the quality of the companies they own, and there is no pressure for quarter to quarter performance. But, and there is always a but, if they are successful you have to pay them 20%, which is a very high hurdle rate. But he feels that if there were truly a fair deal structure, you would never want to invest in the public equity markets.

I am not going to regurgitate the entire conversation, because I do think it is a worthwhile listen. But I am going to close with the question of how Swensen finds people with whom he is willing to invest . He indicated that he used to have a rather long list of the characteristics he wanted in an investment firm. But over time he found that the most important thing is the character and quality of the people running the investment firm. It is also the second, third, and fourth most important thing. He is not looking for people who are going to gather lots of assets at high fees, driven by making a lot of money. He looks for people who define winning as producing great investment returns. In today’s world however, that is a very difficult thing for an outsider to assess.

You will often hear the comment, “we eat our own cooking.” That can be a relative thing. Some would say if a manager has a million dollar commitment in one of his funds, that is quite a statement. Yet if his total compensation (all–in compensation, not just what is told to the fund trustees) has been thirty million dollars a year for the last seven years, and the manager’s fund investment is still the same one million, that is not a very big statement. As an example, Polaris Global Value Fund was recently soliciting shareholder approval for some changes. A proxy document was sent out, which disclosed that fund manager Bernie Horn and his wife owned 15% of the fund, which is roughly a 75 million dollar investment. Now that’s a statement.

Finally, Swensen says you can make money investing in the public markets, but you have to do it with managers who take a long-term point of view. Specifically, they are truly investing with a three to five year time horizon. The other thing that he suggested is that you try and find managers who take a private market approach to the public markets. They invest in large concentrated positions, and try and become partners with the management, working to improve the company. The key is looking for intelligent intermediate and long-term strategies that are attuned to improving the company. He says few do it, but the ones that do achieve powerful returns.

This reminds me of a mistake we as managers made some years ago, that my friend and former colleague Clyde McGregor used to point out in client meetings. And that was that as managers, we had allowed ourselves to be hoodwinked, to drink the Kool Aid as to the options packages which we used to have to vote on proposed by managements. At the time, we thought it was a good thing to align management interests with the shareholders. And what we found was that the management’s interests always took priority, and that ownership of the business would be incrementally but consistently transferred to management over time, regardless of how well the business was doing, and the shareholder investment diluted accordingly. The short-term focus was hitting the targets to trigger the option packages. In retrospect, what should have been done and should be done is to let no retiring or departing executive sell any stock owned as a result of options awarded, for a period of five years after leaving the company.

Tidbits

A couple of points raised by the Financial Times at month end in their global fund management section.

- Black Rock is shifting people and resources to San Francisco as part of a plan to increase its focus on technology and innovation. Their argument is that the cutting edge of innovation in this country is on the West Coast. I suspect the cutting edge for innovation may be that part of the country west of the Mississippi. While California has many strengths, it also has a cost of living that makes it hard to attract and keep a younger generation of employee there. That said, it is obvious that Black Rock is looking to be a leader in the uses of Artificial Intelligence in portfolio management, and is positioning itself accordingly.

- Will soft dollars ever go away? Or rather, will managers have to fund investment research with hard dollars out of their own P&l statement, rather than using commissions generated by the investment of client funds to widen the investment manager’s profit margins. Europe, where governance and transparency have taken root to a far greater extent than in the U.S., has adopted strict rules on the ability of asset managers to pay for investment research as part of a “bundle” of services. At what point will similar rules come into being in the U.S., and actually be enforced. Probably Wall Street will delay as long as they can, or at least until the current generation of owner/managers have cashed out.

- Will the Fiduciary Rule be delayed even further from implementation. Look for this to be resolved in 2018 as there is increasing push back against investment professionals acting in their own best interests rather than those of the client.

Happy Holidays!