Dear friends,

Augustana, my longtime academic home for those of you who don’t know, seems to grow some odd things.

But, too, some awfully joyful moments (at, in this case, Diwali, the Festival of Lights).

and

There are times when their enthusiasm, ill-informed, ill-directed and immature though it sometimes might be, makes much good possible.

Meanwhile, the grown-ups audition for Men Behaving Badly

October saw a remarkable run of news implicating some of the industry’s oldest and most visible players.

Morningstar and The Wall Street Journal launch a ferocious slap fight.

Those brutes!

“When elephants fight, it is the grass that gets trampled.” Yeah, so the nation’s largest newspaper and the nation’s largest … well, whatever Morningstar is now, are in another of the inevitable, periodic tussles. Short version, WSJ: Morningstar is a virtual monopoly and a bully whose marketers are peddling the equivalent of patent medicine to the hicks. Short version, Morningstar: The Wall Street Journal is staffed by a bunch of disgruntled former English majors who never took stats.

If you’re interested in the tedious exchange, MFWire offers a bearable take on them. Our colleague Sam Lee, formerly a Morningstar editor and now president of SVRN Asset Management, tries to get to the bigger problem: not the stars, but how they’re used.

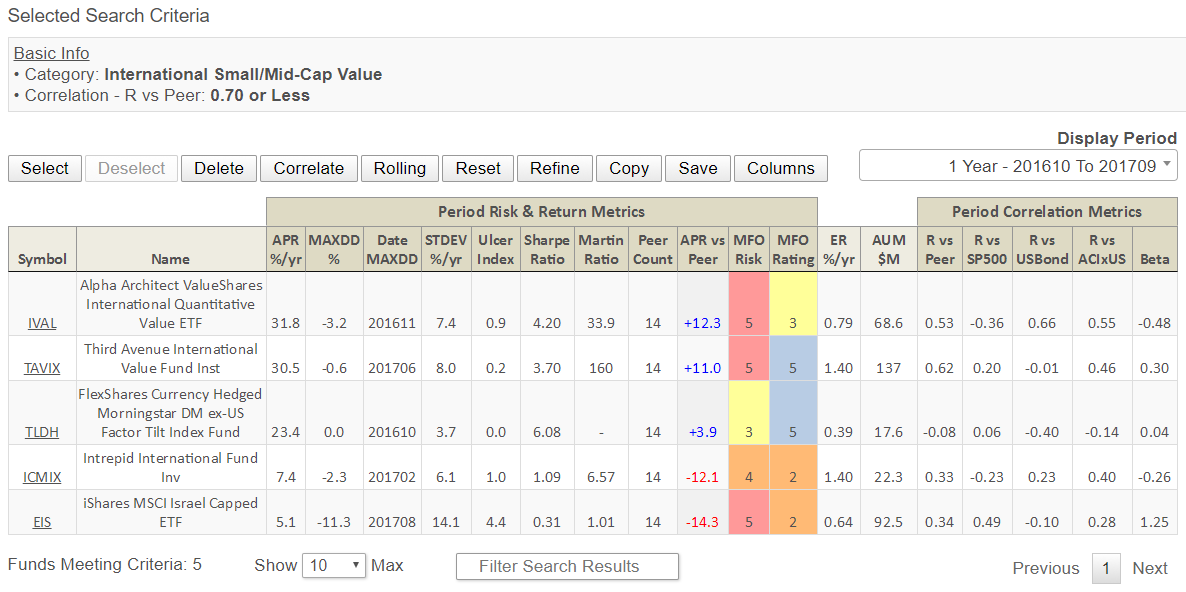

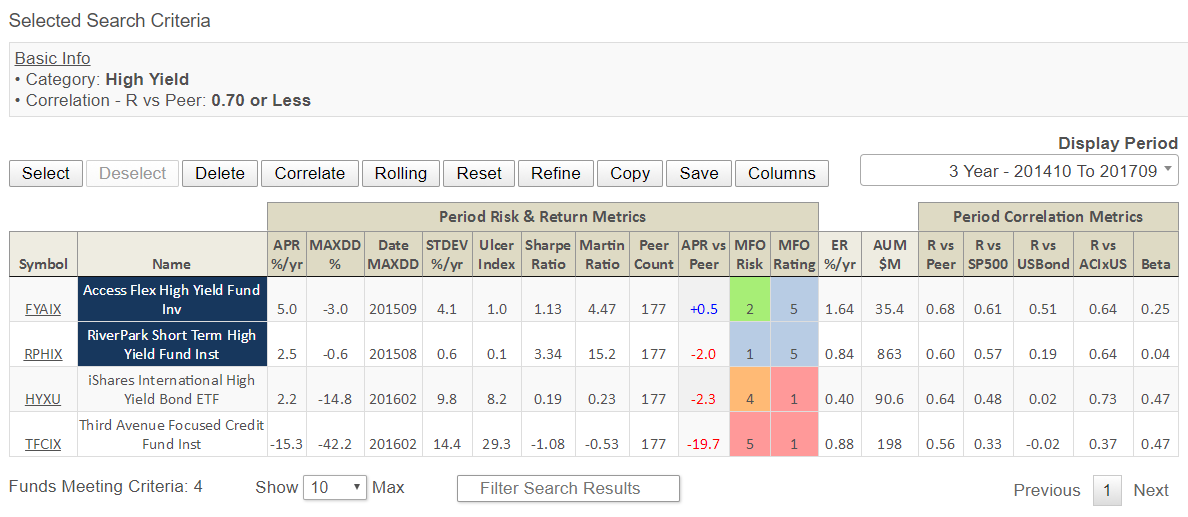

MFO’s argument hasn’t been changed by the recent exchange. The analyst ratings focus on large funds and virtually ignore small, interesting ones. (“Three things we do not know, but which might be true,” April 2017). The star ratings are directionally useful at the extremes; that is, five star funds mostly remain reasonable choices over the succeeding five to ten years. That is, they’re apt to remain in business and maintain star ratings of three or above. One-star funds mostly remain bad choices over the succeeding five to ten years. That is, they’re apt to liquidate or post continued low ratings. For funds in the middle, they’re barely worth noticing.

TIAA gets a substantial slap

TIAA – recently TIAA-CREF and long ago Teachers Insurance Annuity Association, a non-profit underwritten by Andrew Carnegie – is facing serious charges of financial impropriety. Stories in Inside Higher Ed, Investment News, Barron’s, and the New York Times all report on charges by whistle-blowers that TIAA has resorted to the same sorts of sales sleaze that has undone other firms. According to the whistleblowers and legal filings, TIAA has been pressuring employees to move affluent investors into more complicated, higher cost products than they need. The success of that strategy would depend, in part, on the remnants of TIAA’s halo from the days in which it was seen as the ultra-frugal protector of the interests of folks in the non-profit sector.

TIAA’s responses ranged from the irrelevant (“we’ve paid out $394 billion in benefits over the years”) and superficial (“we’re highly transparent and ethical”) to the downright dodgy (“our advisers don’t receive sales commissions,” a point unrelated to the actual allegations).

Nir Kaissar, writing for Bloomberg, goes beyond the legal questions to pose a more fundamental question: is TIAA systematically overcharging and underperforming? (“TIAA’s devotion to investors can start with fees,” 11/1/2017). TIAA has, in the past, explained that a portion of their fund fees underwrites the work of the firm’s many consultants, who provide investment advice at no charge to plan participants. That’s a service not typically offered by mutual fund companies, though it’s certainly a claim made problematic if the charges leveled by the Times and others prove true.

Bogle continues to grouch at Vanguard

The headlines from an interview Bogle gave to Christine Benz of Morningstar tend to read “Vanguard almost too big.” The substance of the interview seems to be that Vanguard can’t reap additional economies of scale, and so can’t reduce expenses much further. (Yawn.) The other half of Bogle’s fear is that Vanguard and two or three of its brethren will be declared an oligopoly, and a threat to the competitive marketplace. That might, he fears, invite government regulation. Perhaps it’s time to “take the foot off the accelerator and ease it gently over to the brake.”

At about the same time, a more interesting criticism of Vanguard and its business model arose in a Barron’s article entitled “Vanguard’s genocide problem” (10/28/2017). A group of Vanguard’s shareholders, led by a team from Harvard Law, are introducing a resolution asking the firm not to underwrite genocide. As a practical matter, they ask Vanguard not to invest in firms that “substantially contribute to genocide or crimes against humanity.” Vanguard’s response is, “not our problem, we need to leave it to Trump and the Congress.”

Uhhhh …

Vanguard’s two specific claims are “Vanguard cannot manage the funds in an effective manner” if it has to accommodate the social and political beliefs of its investors and “an index fund is required to track an index, and if we don’t track that index, it introduces tracking error and harms our investor returns.”

Uhhhh …

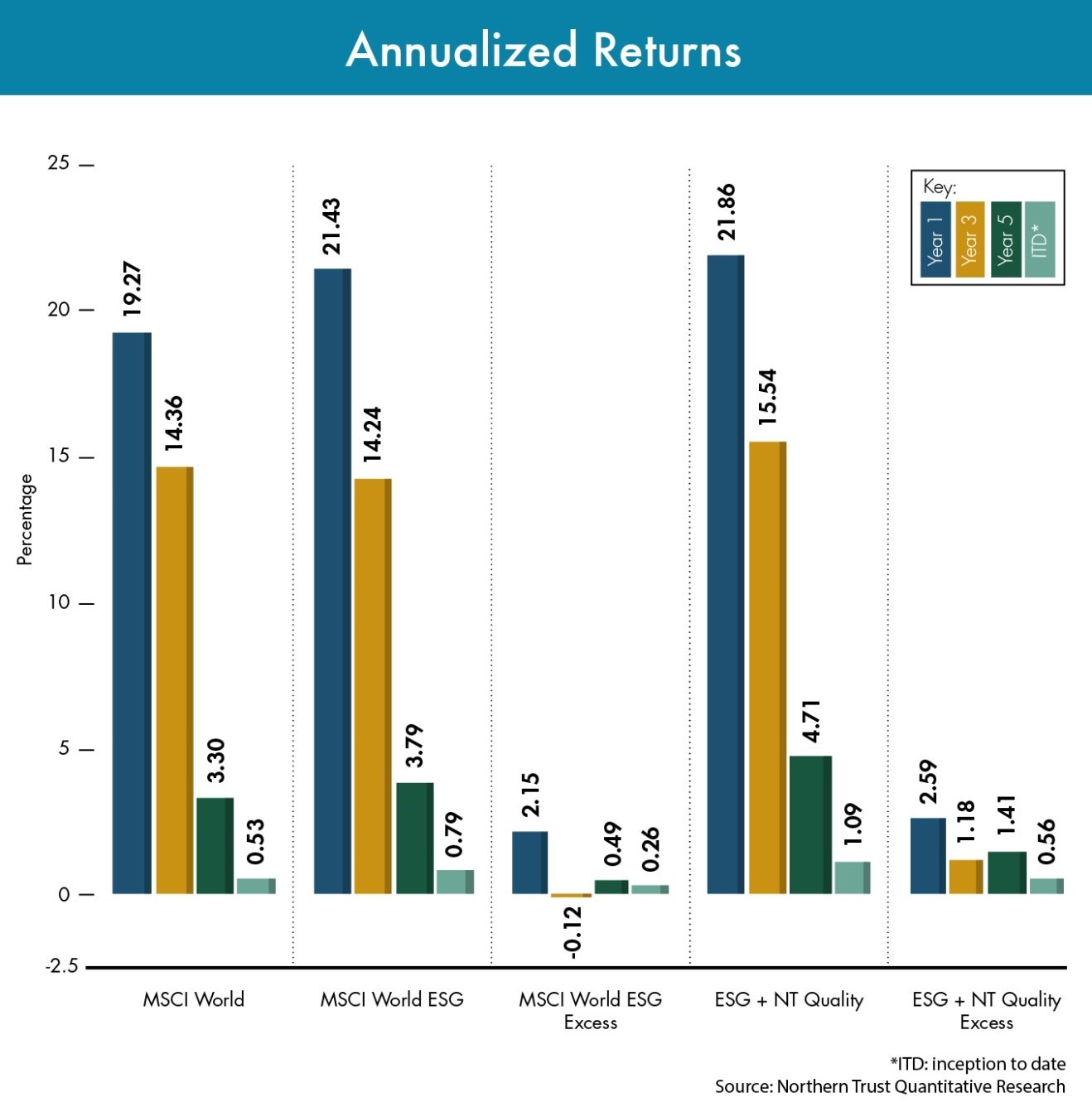

There are indexes that they could choose to track; indeed, Vanguard does offer one ESG index fund (Vanguard FTSE Social Index Fund VFTSX) out of the 180 funds in its lineup. Why only one fund, and no active funds? Why make an argument like “tracking error reduces investor returns” when it doesn’t, though it does create other problems? The likeliest answer is, “not our problem,” which is less troubling in a firm controlling $44 million rather than one controlling $4.4 trillion.

Meanwhile, the dumb article of the month competition goes to …

A bunch of articles debating the trenchant question, “could a crash like 1987 happen again?” The one word article that follows that headline would be, “Yes.”

And, Thanks!

Our special thanks, in this season of thanks giving, to our stalwart subscribers, Deb, Greg, Brian. A big thank you, too, to Roger for your generous donation. And, to Marvin, we really appreciate your kind contribution. We couldn’t keep going without your support.

As ever,

Ensemble is managed by Sean Stannard-Stockton, and much of his career has been in service to high net worth individuals and philanthropic families. From 2007-11, he developed a considerable public following for this

Ensemble is managed by Sean Stannard-Stockton, and much of his career has been in service to high net worth individuals and philanthropic families. From 2007-11, he developed a considerable public following for this