Sometimes it is sensible to be scared of being in the stock market. Those times are rare. I want to describe them from the perspective of a value investor, who only cares about the future cash flows of his investments; I am not offering a method of short-term market timing.

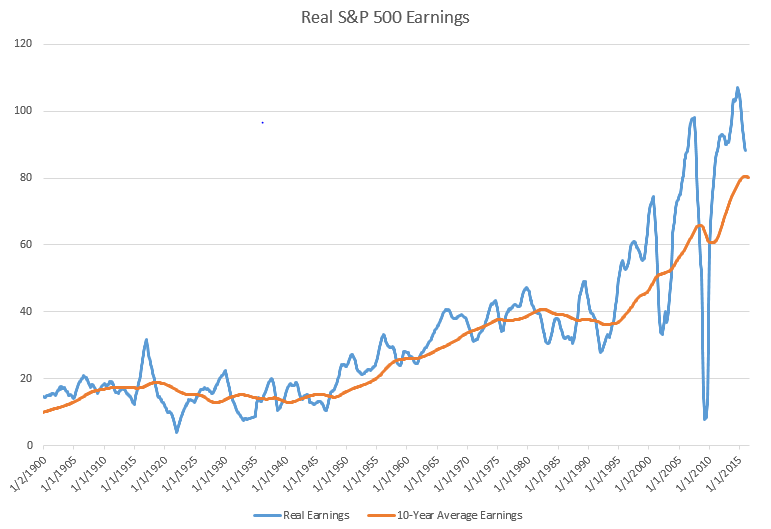

The key fact to grasp is just how resilient corporate earnings are in a big, developed country with strong institutions. The chart below shows the per-share inflation-adjusted earnings of the S&P 500 as well as its 10-year moving average. Though there are violent swings in the per-share earnings series, the moving average shows that the normalized earnings power of U.S. publicly traded corporations grew right through them, rarely reversing for long. Over this period, the U.S. experienced the Great Depression, two world wars, the Cold War, massive corporate tax hikes, oil crises, stagflation, corrupt and incompetent leaders, the 9/11 attacks, countless scandals in leading corporations, the financial crisis and so on.

To the long-term value investor, there are really only a handful of circumstances that warrant a retreat from the stock market:

Prices are so high that the return on stocks over the long run cannot plausibly be much higher than that of other assets such as bonds. During the dot-com bubble, the cyclically-adjusted earnings yield of the market fell to a little over 2% while 30-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities yielded over 4%. For a value-oriented investor to have justified owning the stock market as a whole, he had to assume—dream of, really—fantastically high earnings growth.

The future earnings power of the market is severely impaired or destroyed and this fact is not reflected in prices. This scenario is apocalyptic and has never occurred in the U.S. For a large, developed country’s corporate sector to be permanently maimed, it would either have to be bombed to rubble as Germany and Japan were during World War II or property rights would have to disappear as in Russia during the Russian Revolution. Severe recessions do not noticeably dent the stock market’s future earnings power. A rule of thumb in determining whether a market’s earnings power is at risk of permanent impairment is if significant numbers of citizens are fleeing or want to flee the country for their personal safety.

Discount rates will rise a lot and stay high for a long time. In other words, investors for whatever reason will demand a much lower valuation in stocks, requiring current prices to fall a lot. During the 1970s and early 1980s, rising inflation and nominal interest rates caused investors to demand absurdly low valuations to own stocks. As inflation and interest rates ratcheted up, stock valuations kept ratcheting down. (With the benefit of hindsight, many analysts think that investors were suffering from the money illusion, using the era’s high nominal rates to discount real earnings.) This is a blessing for some. Current dollars invested in the market will take a big, permanent hit, but any future dollars invested in the market will earn a higher rate of return. A secular rise in discount rates is a massive transfer of wealth from the old, who have much of their net worth in financial assets, to the young, who have decades of earnings ahead of them that they can plow into cheap financial assets.

How does this apply to the current market outlook? Valuations are high, but not implausibly high given real yields on bonds. The U.S. stock market’s cyclically-adjusted earnings yield is around 4% while the 30-year TIPS yields less than 1%. Moreover, today’s problems are trivial compared to the existential threats that have loomed in the past. Even if the Eurozone and China blew up at the same time and threw the world into another depression, the long-run underlying earnings power of the rich world’s corporate sector will very likely not be permanently devastated. Valuations would cheapen, for sure, but that would indicate a buying opportunity. (Investors in developing markets, on the other hand, would probably take a permanent hit.)

What concerns me most is that interest rates—real and nominal—are so low everywhere. If the world were to enter an era of rising interest rates as we experienced in the 70s and early 80s, the mighty tailwind that’s boosted valuations over the past 30-plus years would turn into a long-lived headwind. This is a truly frightening scenario that implies years or even decades of puny returns in virtually all financial assets.

Contrast these considerations with media chatter. Everyone talks about and focuses on things that do not truly affect the intrinsic value of the market. The times to be scared are when 1) everyone is euphoric and realistic appraisals of future earnings cannot justify current prices, 2) people are fleeing the country or want to flee the country due to fears over personal safety, or 3) real rates enter a period of secular increases.