Leigh Walzer, founder and principal of Trapezoid, LLC. Leigh’s had a distinguished career working in investment management, in part in the tricky field of distressed securities analysis. He plied that trade for seven years with Michael Price and the Mutual Series folks. He followed that with a long stint as a director at Angelo, Gordon & Co., a well-respected alternatives manager and a couple private partnerships. Through it all, Leigh has been insatiably curious about not just “what works?” but, more importantly, “why does it work?” That’s the work now of Trapezoid LLC.

By Leigh Walzer

Readers of a certain age will remember when winter meant putting on the snow tires. All-season tires were introduced in 1978 and today account for 96% of the US market. Not everyone is sure this is a good idea; Edmunds.com concludes “snow and summer tires provide clear benefits to those who can use them.”

As we begin 2016, most of the country is getting its first taste of winter weather. “Putting on the snow tires” is a useful metaphor for investors who are considering sacrificing performance for safety. Growth stocks have had a great run while the rest of the market sits stagnant. Fed-tightening, jittery credit markets, tight-fisted consumer, commodity recession, and sluggishness outside the US are good reasons for investor caution.

Some clients have been asking if now is a good time to dial back allocations to growth. In other words, should they put the snow tires on their portfolio.

The dichotomy between growth and value and the debate over which is better sometimes approaches theological overtones. Some asset allocators are convinced one or the other will outperform over the long haul. Others believe each has a time and season. There is money to be made switching between growth and value, if only we had 20/20 hindsight about when the business cycle turns.

When has growth worked better than value?

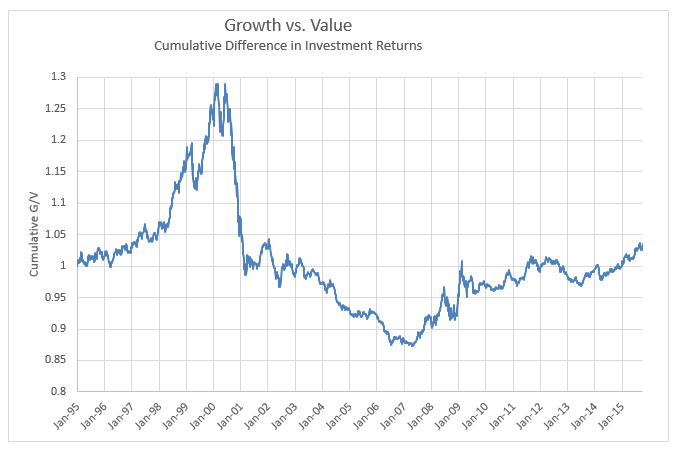

Historically, the race between growth and value has been nearly a dead heat. Exhibit 1 shows the difference in the Cumulative return of Growth and Value strategies over the past twenty years. G/V is a measure of the difference in return between growth and value in a given period Generally speaking, growth performed better in the 90s, a period of loose money up to the internet bust. Value did better from 2000-2007. Since 2007, growth has had the edge despite a number of inflections. Studies going back 50 years suggest value holds a slight advantage, particularly during the stagflation of the 1970s.

Exhibit I

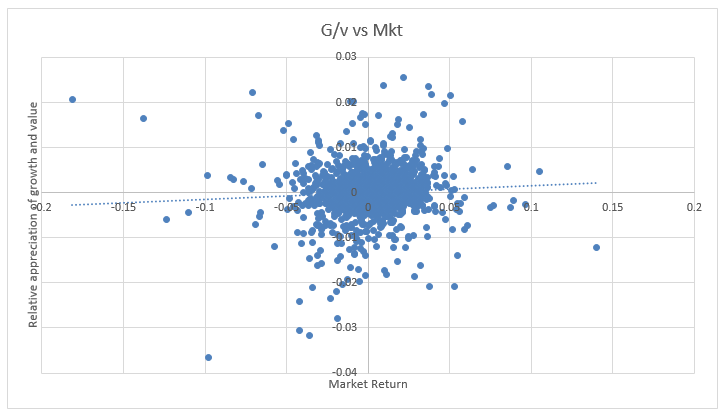

Growth tends to perform better in up-markets. This relationship is statistically valid but the magnitude is almost negligible. Over the past twenty years Trapezoid’s US Growth Index had a beta of 1.015 compared with 0.983 for Value.

Exhibit II

The conventional wisdom is that growth stocks should perform better early to mid-cycle while value stocks perform best late in the business cycle and during recession. That might loosely describe the 90s and early 2000s. However, in the run up the great recession, value took a bigger beating as financials melted down. And when the market rebounded in April 2009, value led the recovery for the first six months.

Value investors expect to sacrifice some upside capture in order to preserve capital during declining markets. Exhibit III, which uses data from Morningstar.com about their Large Growth (“LG”) and Large Value (“LV”) fund categories, shows the reality is less clear. In 2000-2005 LV lived up to its promise: it captured 96% of LG’s upside but only 63% of its downside. But since 2005 LV has actually participated more in the downside than LG.

Exhibit III |

2001-2005 | 2006-2010 | 2011- 2015 |

| LG Upside Capture | 105% | 104% | 98% |

| LG Downside Capture | 130% | 101% | 106% |

| LV Upside Capture | 101% | 99% | 94% |

| LV Downside Capture | 82% | 101% | 111% |

| LV UC / LG Up Capt | 96% | 95% | 97% |

| LV DC / LG Dn Capt | 63% | 100% | 104% |

Recent trend

In 2015 (with the year almost over as of this writing), value underperformed growth by about 5%. Value funds are overweight energy and underweight consumer discretionary which contributed to the shortfall.

Can growth/value switches be predicted accurately?

In the long haul, the two strategies perform nearly equally. If the weatherman can’t predict the snow, maybe it makes sense to leave the all-season tires on all year.

We can look through the historical Trapezoid database to see which managers had successfully navigated between growth and value. Recall that Trapezoid uses the Orthogonal Attribution Engine to attribute the performance of active equity managers over time to a variety of skills. Trapezoid calculates the contribution to portfolio return from overweighting growth or value in a given period. We call this sV.

Bear in mind that Trapezoid LLC does not call market turns or rate sectors for timeliness. And Trapezoid doesn’t try to forecast whether growth or value will work better in a given period. But we do try to help investors make the most of the market. And we look at the historic and projected ability of money managers to outperform the market and their peer group based on a number of skills.

The Trapezoid data does identify managers who scored high in sV during particular periods. Unfortunately, high sV doesn’t seem to carry over from period to period. As Professor Snowball would say, sV lacks predictive validity; the weatherman who excelled last year missed the big storm this year. However, the data doesn’t rule out the possibility that some managers may have skill. As we have seen, growth or value can dominate for many years, and few managers have sufficient tenure to draw a strong conclusion.

We also checked whether market fundamentals might help investors allocate between growth and value. We are aware of one macroeconomic model (Duke/Fuqua 2002) which claims to successfully anticipate 2/3 of growth and value switches over the preceding 25 years.

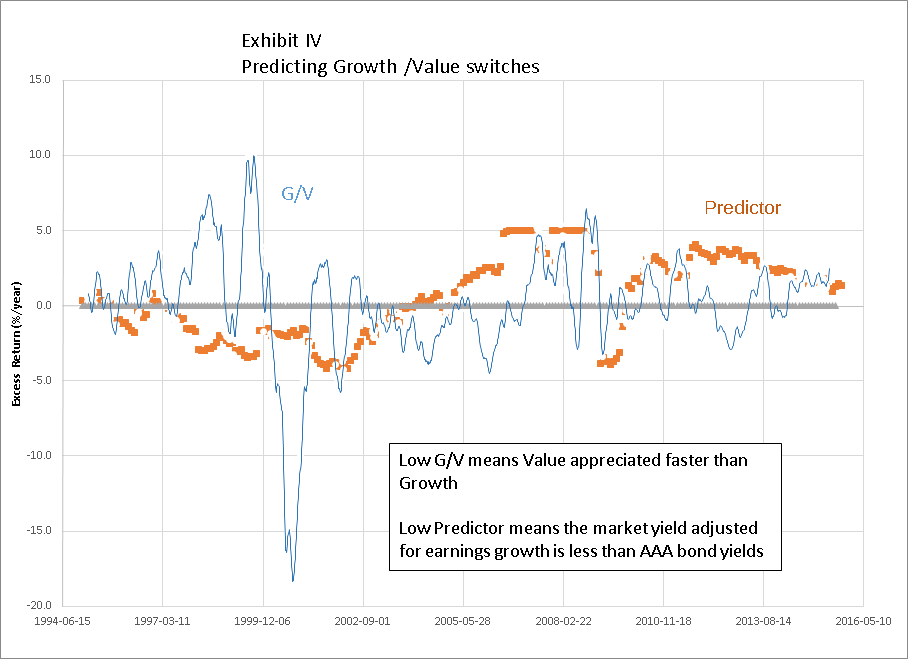

One hypothesis is that value excels when valuations are stretched while growth excels when the market is not giving enough credit to earnings growth. In principle this sounds almost tautologically correct. However, implementing an investment strategy is not easy. We devised an index to see how much earnings growth the market is pricing in a given time (S&P500 E/P less 7-year AAA bond yield adjusted for one year of earning growth). When the index is high, it means either the equity market is attractive relative bonds or that the market isn’t pricing in much earnings growth. Conversely, when the index is low it means valuations of growth stocks are stretched and therefore investors should load up on value. We looked at data from 1995-2015 and compared the relative performance of growth and value strategies over the following 12 months. We expected that when the index is high growth would do better.

Exhibit IV

There are clearly times when investors who heeded this strategy would have correctly anticipated investing cycles. We found the index was directionally correct but not statistically significant. Exhibit IV shows the Predictor has been trending lower in 2015 which would suggest that the growth cycle is nearly over.

All-Weather Managers

Since it is hard to tell when value will start working, investors could opt for all-weather managers, i.e. managers with a proven ability to thrive during value and growth periods.

We combed our database for active equity managers who had an sV contribution of at least 1%/year in both the growth era since 1q07 and the value market which preceded it. Our filter excludes a large swath of managers who haven’t been around 9 years. Only six funds passed this screen – an indication that skill at navigating between growth and value is rare. We knocked out four other funds because, using Trapezoid’s standard methodology, projected skill is low or expenses are high. This left just two funds

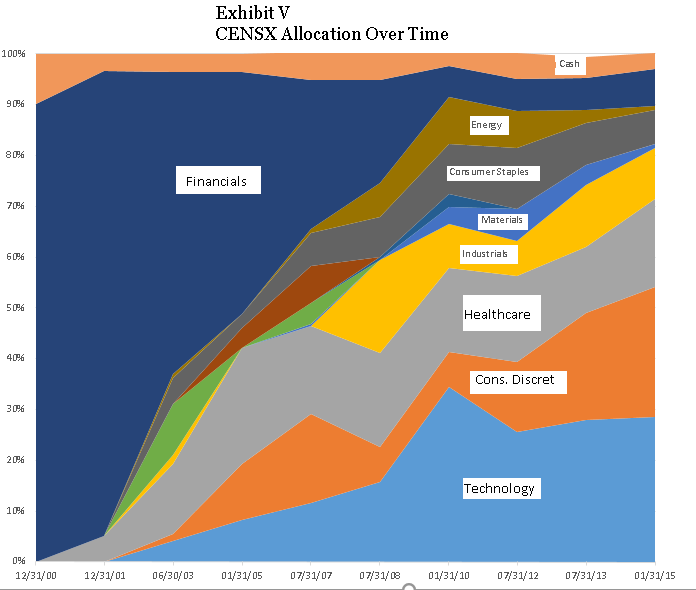

Century Shares Trust (CENSX), launched in 1928, is one of the oldest mutual funds in the US. The fund tracks itself against the Russell 1000 Growth Index but does not target a particular sector mix and apply criteria like EV/EBITDA more associated with value. Expenses run 109bps. CENSX’s performance has been strong over the past three years. Their long-term record selecting stocks and sectors is not sufficient for inclusion in the Trapezoid Honor Roll.

Does CENSX merit extra consideration because of the outstanding contribution from rotating between growth and value? Serendipity certainly plays a part. As Exhibit V illustrates, the current managers inherited in 1999 a fund which was restricted by its charter to financials, especially insurance. That weighting was very well-suited to the internet bust and recession which followed. They gradually repositioned the portfolio towards large growth. And he has made a number of astute switches. Notably, he emphasized consumer discretionary and exited energy which has worked extremely well over the past year. We spoke to portfolio manager Kevin Callahan. The fund is managed on a bottom-up fundamentals basis and does not have explicit sector targets. But he currently screens for stocks from the Russell 1000 Growth Index and seem reluctant to stray too far from its sector weightings, so we expect growth/value switching will be much more muted in the future.

Does CENSX merit extra consideration because of the outstanding contribution from rotating between growth and value? Serendipity certainly plays a part. As Exhibit V illustrates, the current managers inherited in 1999 a fund which was restricted by its charter to financials, especially insurance. That weighting was very well-suited to the internet bust and recession which followed. They gradually repositioned the portfolio towards large growth. And he has made a number of astute switches. Notably, he emphasized consumer discretionary and exited energy which has worked extremely well over the past year. We spoke to portfolio manager Kevin Callahan. The fund is managed on a bottom-up fundamentals basis and does not have explicit sector targets. But he currently screens for stocks from the Russell 1000 Growth Index and seem reluctant to stray too far from its sector weightings, so we expect growth/value switching will be much more muted in the future.

The other fund which showed up is Cohen & Steers Global Realty Fund (CSSPX). The entire real estate category had positive sV over the past 15-20 years; real estate (both domestic and global) clobbered the market during the value years, gave some back in the run-up to the financial crisis, and has been a market performer since then.

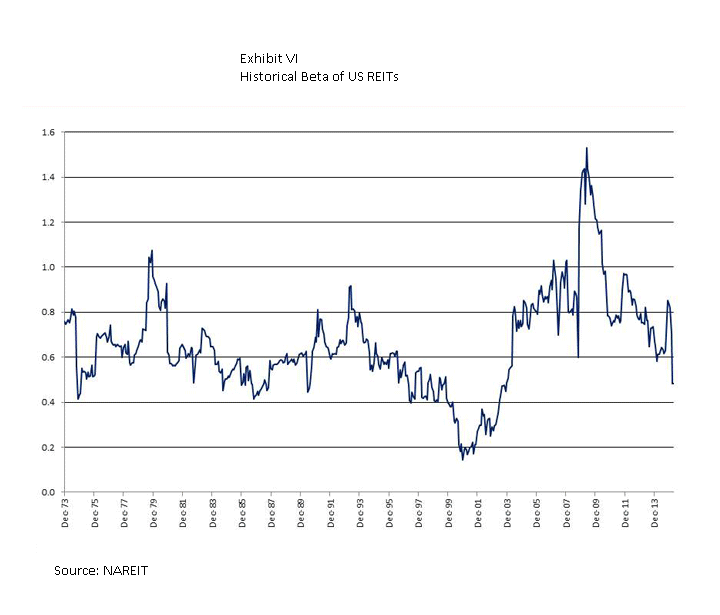

We are not sure how meaningful it is that CSSPX made this list over some other real estate funds with similar focus and longevity. Investors may be tempted to embrace real estate as an all-weather sector. But over the longer haul real estate has had a more consistent market correlation with beta averaging 0.6 which means it participated equally in up and down markets.

More complete information can be found at www.fundattribution.com. MFO readers can sign up for a free demo. Please click the link from the Model Dashboard (login required) to the All-Weather Portfolio

The All-Season Portfolio

Since we are not sure that good historic sV predicts future success and managers with a good track record in this area are scarce, investors might take a portfolio approach to all-season investing.

- Find best of breed managers. Use Trapezoid’s OAE to find managers with high projected skill relative to cost. While the Trapezoid demo rates only Large Blend managers (link to the October issue of MFO), the OAE also identifies outstanding managers with a growth or value orientation.

- Strike the right balance. Many thoughtful investors believe “value is all you need” and some counsel 100% allocation to growth. Others apply age-based parameters. Based on the portfolio-optimization model I consulted and my dataset, the recommended weighting of growth and value is nearly 50/50. In other words: snow tires on the front, summer tires on the back. (Note this recommendation is for your portfolio, for auto advice please ask a mechanic.) I used 20 years of data; using a longer time frame, value might look better

Bottom line:

It is hard to predict whether growth or value will outperform in a given year. Demonstrable skill shifting between growth and value is surprisingly scarce. Investors who are content to be passive can just stick to funds which index the entire market. A better strategy is to identify skillful growth and value managers and weight them evenly.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

The stuff Leigh shares here reflects the richness of the analytics available on his site and through Trapezoid’s services. If you’re an independent RIA or an individual investor who need serious data to make serious decisions, Leigh offers something no one else comes close to. More complete information can be found at www.fundattribution.com. MFO readers can sign up for a free demo.