Update: This fund has been liquidated.

Objective and strategy

The Fund seeks to achieve long-term capital growth of capital by investing in an all-cap portfolio of undervalued stocks. The managers look for three qualities in their portfolio companies:

- High quality business, those companies that have a competitive advantage, high profit margins and returns on capital, sustainable results and/or low-cost operations,

- High quality management, an assessment grounded in the management’s record for ethical action, inside ownership and responsible allocation of capital

- Undervalued stock, which factors in future cash flow as well as conventional measures such as price/earnings and price/sales.

Mr. Martin summarizes his discipline this way: “When companies we favor reach what our analysis concludes are economically compelling prices, we will buy them. Period.” If there are no compelling bargains in the securities markets, the Fund may have a substantial portion of its assets in cash or cash equivalents such as short-term Treasuries. The fund is non-diversified and has not yet had more than 9% in equities, although that would certainly rise if stock prices fell dramatically.

Adviser

Martin Capital Management (MCM), headquartered in Elkhart, IN. Established in 1987, MCM has stated an ongoing commitment to a “rational, disciplined, concentrated, value-oriented investment philosophy.” Their first priority is preservation of capital, but seek opportunities for growth when they find underpriced, but well-run companies. They manage about $160 million, roughly 10% of which is in their mutual fund.

Manager

Frank Martin is portfolio manager, as well as the founder and CIO of the adviser. A 1964 graduate of Northwestern University’s investment management program, Mr. Martin went on to obtain an MBA from Indiana University. He does a lot of charitable work, including his role as founder and chairman of the board of DreamsWork, a mentoring and scholarship program for inner-city children. Mr. Martin has published two books on investing, Speculative Contagion and A Decade of Delusions. He’s assisted by a four person research team.

Strategy capacity and closure

Mr. Martin allows that the theoretical capacity is “pretty darn large,” but that having a fund that was big is “too distracting” from the work on investing so he’d look for a manageable portfolio size.

Active share

Not formally calculated but undoubtedly near 100, given a portfolio with just four stocks.

Management’s stake in the fund

Mr. Martin has invested over $1 million in the fund and, as of the early 2014, is the fund’s largest shareholder. No member of the board of directors has invested in the fund but then four of the six directors haven’t invested in any of the 18 funds they oversee. The firm’s employees invest in this strategy largely through separately managed accounts, which reflects the fact that the fund did not exist when his folks began investing. The portfolio is small enough that Mr. Martin knows many of his shareholders, five of whom own 35% of the retail shares between them.

Opening date

May 03, 2012

Minimum investment

$2,500 for an initial investment for retail shares. $100 minimum for subsequent investments.

Expense ratio

1.39%, after waivers, on about $15 million in assets (as of April 2014). There’s also an institutional share class (MFVIX) with an e.r. of 0.99% and a $100,000 minimum.

Comments

Absolute value investors are different. These are guys who don’t want to live at the edge. They take the phrase “margin of safety” very seriously. For them, “risk” is about “permanent losses,” not “foregone gains.” They don’t BASE jump. They don’t order fugu. They don’t answer the question “I wonder if this will hold my weight?” by hopping on it. They do drive, often in Volvos and generally within five MPH of the posted speed limit, to Omaha every May to hear The Word from Warren and fellowship with like-minded investors.

Unlike relative value and growth guys, they don’t believe that you hired them to pick the best stocks available. They do believe you hired them to compose the best equity portfolio available. The difference is that “the best equity portfolio” might well be one that, potentially for long periods, holds few stocks and huge amounts of cash. Why? Because markets are neither efficient nor rational; they are the aggregated decisions of millions of humans who often move as herds and sometimes as stampeding herds. Those stampedes – sometimes called manias or bubbles, sometimes simply frothy markets or periods of irrational exuberance – are a lot of fun while they last and catastrophic when they end. We don’t know when they will end, but we do know that every market that overshoots on the upside is followed by one that overshoots on the downside.

In general, absolute value investors try to protect you from those entirely predictable risks. Rather than relying on you to judge the state of the market and its level of riskiness, they act on your behalf by leaving early, sacrificing part of the gain in order to spare you as much of the pain as possible.

In general, that translates to stockpiling cash (or implementing some sort of hedging position) when stocks with absolutely attractive valuations are unavailable, in anticipation of being able to strike quickly on the day when attractively-priced stocks are again available.

Mr. Martin takes that caution one step further. In addition to protecting you from predictable risks (“known unknowns,” in Mr. Rumsfeld’s parlance), he has attempted to create a portfolio that offers some protection against risks that are impossible to anticipate (“unknown unknowns” for Mr. Rumsfeld, “black swans” if you prefer Mr. Taleb’s term). His strategy, also drawing from Mr. Taleb’s research, is to create an “antifragile” portfolio; that is, one which grows stronger as the stress on it rises.

Mr. Martin, a value investor with 40 years of experience, has won praise from the likes of Jack Bogle, Jim Grant and Edward Studzinski. Earlier in his career, he ran fully-invested portfolios. In the past 20 years, he’s become less willing to buy marginally-priced stocks and has rarely been more than 70% invested in the market. With the launch of Martin Focused Value Fund in 2011, he moved more decisively into pursuing a barbell strategy in his portfolio, which he believes to be decidedly anti-fragile. The bulk of the portfolio is now invested in short-term Treasuries while under 10% is in undervalued, high-quality equities. In normal markets, the equities will provide much of the fund’s upside while the bonds contribute modest returns. The portfolio’s advantage is that in market crises, panicked investors are prone to bid up the price of the ultra-safe bonds in his portfolio, giving him both downside protection and “dry powder” to deploy when stocks tank.

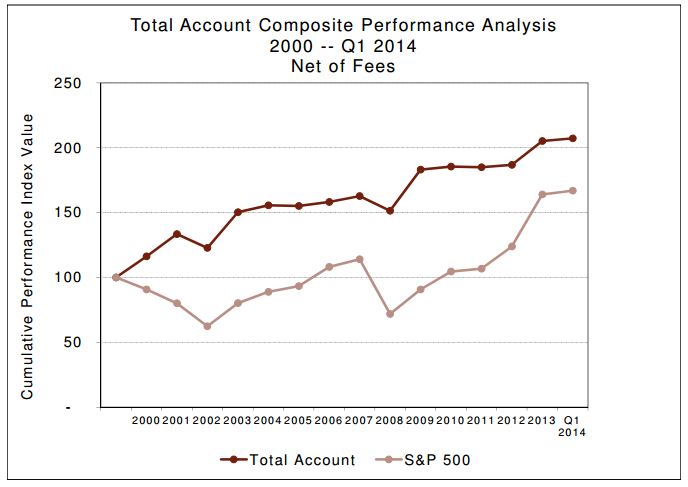

The result is a low volatility portfolio which has produced consistent results. While his mutual fund is new, he’s been using the same discipline in private accounts and those investments have decisively outperformed the S&P this century. The following chart reflects the performance of those private accounts:

Those returns include the effects of some outstanding stock picking. The equity portion of Mr. Martin’s portfolio returned 13.1% annually from 2000 – 2014Q1, while the S&P banked just 3.7% for the same period. He and his analysts are, in short, really talented at picking stocks. Over this same period, the composite had a standard deviation (a measure of volatility) of 3.4% while the S&P 500 bounced 12.3%, a difference of 350%.

Why might you want to consider a low-equity, antifragile portfolio? Like many absolute value investors, Mr. Martin believes that we’re now seeing “a market that seems increasingly detached from its fundamental moorings.” That’s a “known unknown.” He goes further than most and posits the worrisome presence of an unknown unknown. Here’s the argument: corporations can do one of four things with their income (technically, their free cash flow):

- They can invest in the business through new capital expenditures or by hiring new workers.

- They can give money back to their investors in the form of dividends.

- They can buy back shares of the corporation’s stock on the open market.

- They can acquire someone else’s company to add to the corporate empire.

Of these four activities, one and only one – re-investment – is consistently beneficial to a corporation’s long-term prospects. It is also the one that least interests corporate leaders who are being pushed to maximize immediate stock returns; focusing on the long-term now poses a palpable risk of being dismissed if it causes short-term performance to lag.

Amazon’s chief and founder, Jeff Bezos, and Amazon’s stock are both being pounded in mid-2014 because Bezos stubbornly insists on pouring money into research and development and capital projects. Amazon’s stock has fallen 25% YTD through May 1, an event that Bezos can survive when most other CEOs would fall.

“Since 2008, the proportion of cash flow invested in capital assets is the lowest on record” while both the debt to GDP ratio and the amount of margin debt (that is, money borrowed to speculate in the market) are at their highest levels ever. At the same time, the 100 largest companies in the U.S. have spent a trillion dollars buying back stock since 2008 while dividend payments in 2013 were 40% above their 10-year average; by Mr. Martin’s calculation, “90% of cash flow is being expended for purposes that don’t increase the value of most companies over the longer-term.” In short, stock prices are rising steadily for firms whose futures are increasingly at risk.

His aim, then, is to build a portfolio which will, first, preserve investors’ wealth and then grow it over the course of a life.

Potential investors should note two cautions:

- They need to understand that double-digit returns will be relatively rare; his separate account composition had returns above 10% in four of 14 years from 2000-13.

- Succession planning at the firm has not yet born fruit. At 71, Mr. Martin is actively, but so far unsuccessfully, engaged in a search for a successor. He wants someone who shares his passion for long-term success and his willingness to sacrifice short-term gains when need be. One simple test that he’s subjected candidates to is to look at whether their portfolios outperformed the S&P during the 2007-09 meltdown. So far, the answer has mostly been “no.”

Bottom Line

There are some investors for whom this strategy is a very good fit, though few have yet found their way to the fund. Folks who share Mr. Martin’s concern about the effects of perverse financial incentives (or even the growing risks of global technology that’s outracing our ability to comprehend, much less control, its consequences) should consider the fund. Likewise investors who are trying to preserve wealth against the effects of inflation over decades would find a comfortable home here. Folks who are convinced that they can outsmart the market, who are banking on double-digit rights and expect to out-time its gyrations are apt to be disappointed.

Fund website

www.martinfocusedvaluefund.com. He’s got a remarkable body of writings at the fund website, but rather more at the main Martin Capital Management site. His essays are well-written, both substantial and wide-ranging, sort of the antithesis of the usual marketing stuff that passes for mutual fund white papers.