Objective

The fund seeks long-term capital growth by investing exclusively in stocks of companies with significant exposure (50% or more of assets or revenues) to countries with developing economies and/or markets. That investment can occur through ADRs and ADSs. Investment decisions are made in accordance with Islamic principles. The fund diversifies its investments across the countries of the developing world, industries, and companies, and generally follows a value investment style.

Adviser

Saturna Capital, of Bellingham, Washington. Saturna oversees five Sextant funds, the Idaho Tax-Free fund and three Amana funds. The Sextant funds contribute about $250 million in assets while the Amana funds hold about $3 billion (as of April 2011). The Amana funds invest in accord with Islamic investing principles. The Income Fund commenced operations in June 1986 and the Growth Fund in February, 1994. Mr. Kaiser was recognized as the best Islamic fund manager for 2005.

Manager

Nicholas Kaiser with the assistance of Monem Salam. Mr. Kaiser is president and founder of Saturna Capital. He manages five funds (two at Saturna, three here) and oversees 26 separately managed accounts. He has degrees from Chicago and Yale. In the mid 1970s and 1980s, he ran a mid-sized investment management firm (Unified Management Company) in Indianapolis. In 1989 he sold Unified and subsequently bought control of Saturna. As an officer of the Investment Company Institute, the CFA Institute, the Financial Planning Association and the No-Load Mutual Fund Association, he has been a significant force in the money management world. He’s also a philanthropist and is deeply involved in his community. By all accounts, a good guy all around. Mr. Monem Salam, vice president and director of Islamic investing at Saturna Capital Corporation, is the deputy portfolio manager for the fund.

Inception

September 28, 2009.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

Mr. Kaiser directly owned $500,001 to $1,000,000 of Developing World Fund shares and indirectly owned more than $1,000,000 of it. Mr. Salam has something between $10,00 to $50,000 Developing World Fund. As of August, 2010, officers and trustees, as a group, owned nearly 10% of the Developing World Fund.

Minimum investment

$250 for all accounts, with a $25 subsequent investment minimum. That’s blessedly low.

Expense ratio

1.59% on an asset base of about $15 million. There’s also a 2% redemption fee on shares held fewer than 90 days.

Comments

Mr. Kaiser launched AMDWX at the behest of many of his 100,000 Amana investors and was able to convince his board to authorize the launch by having them study his long-term record in international investing. That seems like a decent way for us to start, too.

Appearances aside, AMDWX is doing precisely what you want it to.

Taken at face value, the performance stats for AMDWX appear to be terrible. Between launch and April 2011, AMDWX turned $10,000 into $11,000 while its average peer turned $10,000 to $13,400. As of April 2011, it’s at the bottom of the pack for both full years of its existence and for most trailing time periods, often in the lowest 10%.

And that’s a good thing. The drag on the fund is its huge cash position, over 50% of assets in March, 2011. Sibling Sextant International (SSIFX) is 35% cash. Emerging markets have seen enormous cash inflows. As of late April, 2011, emerging markets funds were seeing $2 billion per week in inflows. Over 50% of institutional emerging markets portfolios are now closed to new investment to stem the flow. Vanguard’s largest international fund is Emerging Markets Stock Index (VEIEX) at a stunning $64 billion. There’s now clear evidence of a “bubble” in many of these small markets and, in the past, a crisis in one region has quickly spread to others. In response, a number of sensible value managers, including the remarkably talented team behind Artisan Global Value (ARTGX), have withdrawn entirely from the emerging markets. Amana’s natural caution seems to have been heightened, and they seem to be content to accumulate cash and watch. If you think this means that “bad things” and “great investment values” are both likely to manifest soon, you should be reassured at Amana’s disciplined conservatism.

The only question is: will Amana’s underperformance be a ongoing issue?

No.

Let me restate the case for investing with Mr. Kaiser.

I’ve made these same arguments in profiling Sextant International (SSIFX) as a “star in the shadows.”

Mr. Kaiser runs four other stock funds: one large value, one large core international (which has a 25% emerging markets stake), one large growth, and one that invests across the size and valuation spectrum. For all of his funds, he employs the same basic strategy: look for undervalued companies with good management and a leadership position in an attractive industry. Buy. Spread your bets over 60-80 names. Hold. Then keep holding for between ten and fifty years.

Here’s Morningstar’s rating (as 4/26/11) of the four equity funds that Mr. Kaiser manages:

| 3-year | 5-year | 10-year | Overall | |

| Amana Trust Income | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« |

| Amana Trust Growth | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« |

| Sextant Growth | «««« | ««« | ««««« | «««« |

| Sextant International | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« |

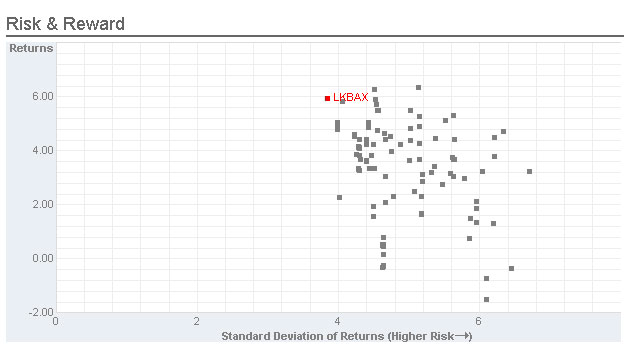

In their overall rating, every one of Mr. Kaiser’s funds achieves “above average” or “high” returns for “below average” or “low” risk.

Folks who prefer Lipper’s rating system (though I’m not entirely clear why they would do so), find a similar pattern:

| Total return | Consistency | Preservation | Tax efficiency | |

| Amana Income | ««««« | «««« | ««««« | ««««« |

| Amana Growth | ««««« | ««««« | ««««« | «««« |

| Sextant Growth | «««« | ««« | ««««« | ««««« |

| Sextant International | ««««« | «« | ««««« | ««««« |

I have no idea of how Lipper generated the low consistency rating for International, since it tends to beat its peers in about three of every four years, trailing mostly in frothy markets. Its consistency is even clearer if you look at longer time periods. I calculated Sextant International’s returns and those of its international large cap peers for a series of rolling five-year periods since with the fund’s launch in 1995. I looked at what would happen if you invested $10,000 in the fund in 1995 and held for five years, then looked at 1996 and held for five, and so on. There are ten rolling five-year periods and Sextant International outperformed its peers in 100% of those periods. Frankly, that strikes me as admirably consistent.

At the Sixth Annual 2010 Failaka Islamic Fund Awards Ceremony (held in April, 2011), which reviews the performance of all managers, worldwide, who invest on Islamic principles, Amana received two “best fund awards.”

Other attributes strengthen the case for Amana

Mr. Kaiser’s outstanding record of generating high returns with low risk, across a whole spectrum of investments, is complemented by AMDWX’s unique attributes.

Islamic investing principles, sometimes called sharia-compliant investing, have two distinctive features. First, there’s the equivalent of a socially-responsible investment screen which eliminates companies profiting from sin (alcohol, porn, gambling). Mr. Kaiser estimates that the social screens reduce his investable universe by 6% or so. Second, there’s a prohibition on investing in interest-bearing securities (much like the 15 or so Biblical injunctions against usury, traditionally defined as accepting an interest or “increase”), which effective eliminates both bonds and financial sector equities. The financial sector constitutes about 25% of the market capitalization in the developing world. Third, as an adjunct to the usury prohibition, sharia precludes investment in deeply debt-ridden companies. That doesn’t mean a company must have zero debt but it does mean that the debt/equity ratio has to be quite low. Between those three prohibitions, about two-thirds of developing market companies are removed from Amana’s investable universe.

This, Mr. Kaiser argues, is a good thing. The combination of sharia-compliant investing and his own discipline, which stresses buying high quality companies with considerable free cash flow (that is, companies which can finance operations and growth without resort to the credit markets) and then holding them for the long haul, generates a portfolio that’s built like a tank. That substantial conservatism offers great downside protection but still benefits from the growth of market leaders on the upside.

Risk is further dampened by the fund’s inclusion of multinational corporations domiciled in the developed world whose profits are derived in the developing world (including top ten holding Western Digital and, potentially, Colgate-Palmolive which generates more than half of its profits in the developing world). Mr. Kaiser suspects that such firms won’t account for more than 20% of the portfolio but they still function as powerful stabilizers. Moreover, he invests in stocks and derivatives which are traded on, and settled in, developed world stock markets. That gives exposure to the developing world’s growth within the developed world’s market structures. As of 1/30/10, ADRs and ADSs account for 16 of the fund’s 30 holdings.

An intriguing, but less obvious advantage is the fund’s other investors.

Understandably enough, many and perhaps most of the fund’s investors are Muslims who want to make principled investments. They have proven to be incredibly loyal, steadfast shareholders. During the market meltdown in 2008, for example, Amana Growth and Amana Income both saw assets grow steadily and, in Income’s case, substantially.

The movement of hot money into and out of emerging markets funds has particularly bedeviled managers and long-term investors alike. The panicked outflow stops managers from doing the sensible thing – buying like mad while there’s blood in the streets – and triggers higher expenses and tax bills for the long-term shareholders. In the case of T. Rowe Price’s very solid Emerging Market Stock fund (PRMSX), investors have pocketed only 50% of the fund’s long-term gains because of their ill-timed decisions.

In contrast, Mr. Kaiser’s investors do exactly the right thing. They buy with discipline and find reason to stick around. Here’s the most remarkable data table I’ve seen in a long while. This compares the investor returns to the fund returns for Mr. Kaiser’s four other equity funds. It is almost universally the case that investor returns trail far behind fund returns. Investors famously buy high and sell low. Morningstar’s analyses suggest s the average fund investor makes 2% less than the average fund he or she owns and, in volatile areas, fund investors often lose money investing in funds that make money.

How do Amana/Sextant investors fare on those grounds?

| Fund’s five-year return | Investor’s five-year return | |

| Sextant International | 6.3 | 12.9 |

| Sextant Growth | 2.5 | 5.3 |

| Sextant Core | 3.8 (3 year only) | 4.1 (3 year only) |

| Amana Income | 7.0 | 9.0 |

| Amana Growth | 6.0 | 9.8 |

In every case, those investors actually made more than the nominal returns of their funds says is possible. Having investors who stay put and buy steadily may offer a unique, substantial advantage for AMDWX over its peers.

Is there reason to be cautious? Sure. Three factors are worth noting:

- For better and worse, the fund is 50% cash, as of 3/31/11.

- The fund’s investable universe is distinctly different from many peers’. There are 30 countries on his approved list, about half as many as Price picks through. Some countries which feature prominently in many portfolios (including Israel and Korea) are excluded here because he classifies them as “developed” rather than developing. And, as I noted above, about two-thirds of developing market stocks, and the region’s largest stock sector, fail the fund’s basic screens.

- Finally, a lot depends on one guy. Mr. Kaiser is the sole manager of five funds with $2.8 billion in assets. The remaining investment staff includes his fixed-income guy, the Core fund manager, the director of Islamic investing and three analysts. At 65, Mr. Kaiser is still young, sparky and deeply committed but . …

Bottom line

If you’re looking for a potential great entree into the developing markets, and especially if you’re a small investors looking for an affordable, conservative fund, you’ve found it!

Company link

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2011. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact [email protected].