Dear friends,

I love language, in both its ability to clarify and to mystify.

Take the phrase “think outside the box.” You’ve heard it more times than you’d care to count but have you ever stopped to wonder: what box are they talking about? Maybe someone invented it for good reason, so perhaps you should avoid breaking the box?

In point of fact, it’s this box:

Here’s the challenge that lies behind the aphorism: link all nine dots using four straight lines or fewer, without lifting the pen and without tracing the same line more than once. There are only two ways to accomplish the feat: (1) rearrange the dots, which is obviously cheating, and (2) work outside the box. For example:

As we interviewed managers this month, Ed Studzinski, they and I got to talking about investors’ perspectives on the future. In one camp there are the “glass half-full” guys. Dale Harvey of Poplar Forest Partners Fund (PFPFX) allowed, for example, that there may come a time to panic about the stock market, but it’s not now. He looks at three indicators and finds them all pretty green:

- His ability to find good investment ideas. He’s still finding opportunities to add positions to the fund.

- What’s going on with the Fed? “Don’t fight the Fed” is an axiom for good reason, he notes. They’ve just slowing the rate of stimulus, not slowing the economy. You get plenty of advance notice when they really want to start applying the brakes.

- What’s going on with investor attitudes? Folks aren’t all whipped-up about stocks, though there are isolated “story” stocks that folks are irrational over.

Against those folks are the “glass half-empty” guys. Some of those guys are calling the alarm; others stoically endure that leaden feeling in the pit of their stomachs that comes from knowing they’ve seen this show before and it never ends well. By way of illustration:

- The Leuthold Group believes that large cap stocks are more than 25% overvalued, small caps much more than that, that there could be a substantial correction and that corrections overshoot, so a 40% drop is not inconceivable.

- Jeremy Grantham of GMO places the market at 65% overvalued. Fortunately, according to a Barron’s interview, it won’t become “a true bubble” until it inflates 30% more and individual investors, still skittish, become “gung-ho.”

- Mark Hulbert notes that “true insider” stock sales have reached their highest level in a quarter century. Hulbert notes that insider selling isn’t usually predictive because the term “insider” encompasses both true insiders (directors, presidents, founders, operating officers) and legal insides (any investor who controls more than 5% of the stock). It turns out that “true” insider selling is predictive of a stock market fall a couple quarters later. He makes his argument in two similar, but not quite identical, articles in Barron’s and MarketWatch. (Go read them.)

And me, you ask? I guess I’m neither quite a glass half full nor a glass half empty sort of investor. I’m closer to a “don’t drop the glass!” guy. My non-retirement portfolio remains about where it always is (25% US stocks with a value bias, 25% international stocks with a small/emerging bias, 50% income) and it’s all funded on auto-pilot. I didn’t lose a mint in ’08, I didn’t make a mint in ’13 and I spend more time thinking about my son’s average (the season starts in the first week of April and he’ll either be on the mound or at second) than about the Dow’s.

“Judge Our Performance Over a Full Market Cycle”

Uh huh! Be careful of what you wish for, Bub. Charles did just check your performance across full market cycles, and it’s not as pretty as you’d like. Here are his data-rich findings:

Ten Market Cycles

In response to the article In Search of Persistence, published in our January commentary, NumbersGirl posted the following on the MFO board:

In response to the article In Search of Persistence, published in our January commentary, NumbersGirl posted the following on the MFO board:

I am not enamored of using rolling 3-year returns to assess persistence.

A 3-year time period will often be all up or all down. If a fund manager has an investing personality or philosophy then I would expect strong relative performance in a rising market to be negatively correlated with poor relative performance in a falling market, etc.

It seems to me that the best way to measure persistence is over 1 (or better yet more) market cycles.

There followed good discussion about pros and cons of such an assessment, including lack of consistent definition of what constitutes a market cycle.

Echoing her suggestion, fund managers also often ask to be judged “over full cycle” when comparing performance against their peers.

A quick search of literature (eg., Standard & Poor’s Surviving a Bear Market and Doug Short’s Bear Markets in the S&P since 1950) shows that bear markets are generally “defined as a drop of 20% or more from the market’s previous high.” Here’s how the folks at Steele Mutual Fund Expert define a cycle:

Full-Cycle Return: A full cycle return includes a consecutive bull and bear market return cycle.

Up-Market Return (Bull Market): A Bull market in stocks is defined as a 20% rise in the S&P 500 Index from its previous trough, ending when the index reaches its peak and subsequently declines by 20%.

Down-Market Return (Bear Market): A Bear market in stocks is defined as a 20% decline in the S&P 500 Index from its previous peak, and ends when the index reaches its trough and subsequently rises by 20%.

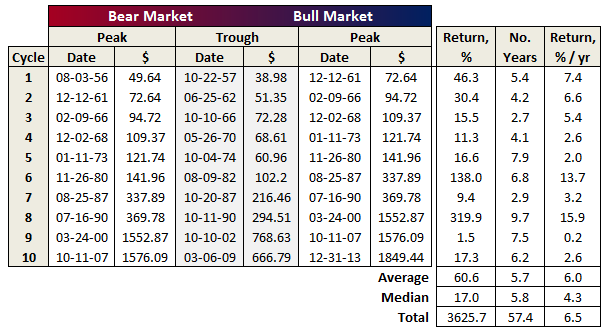

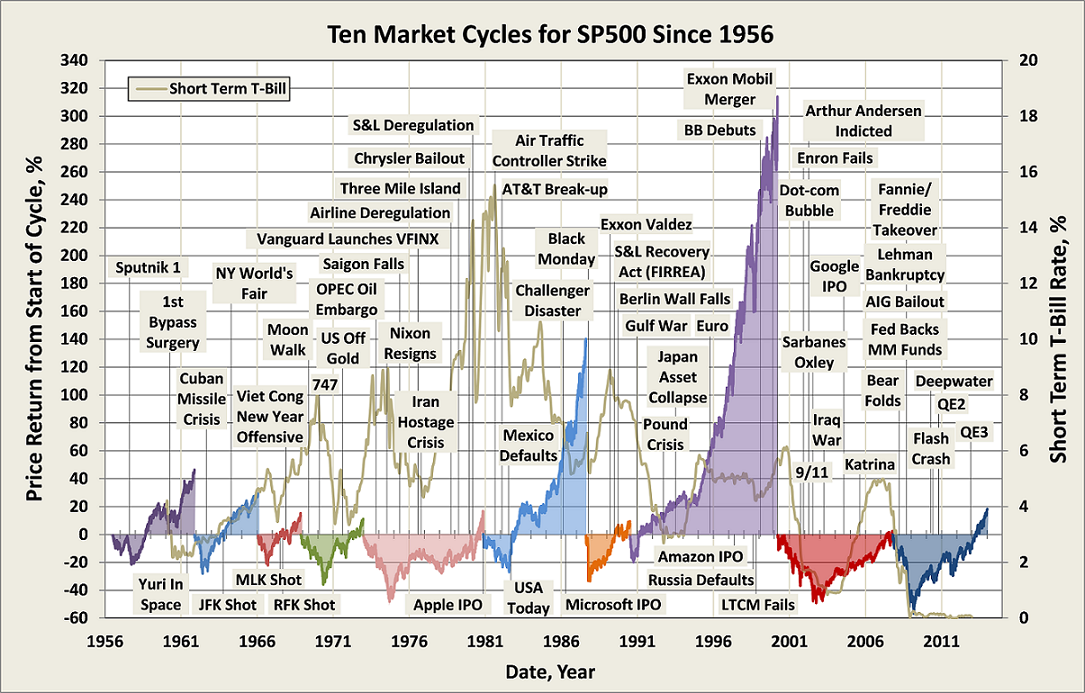

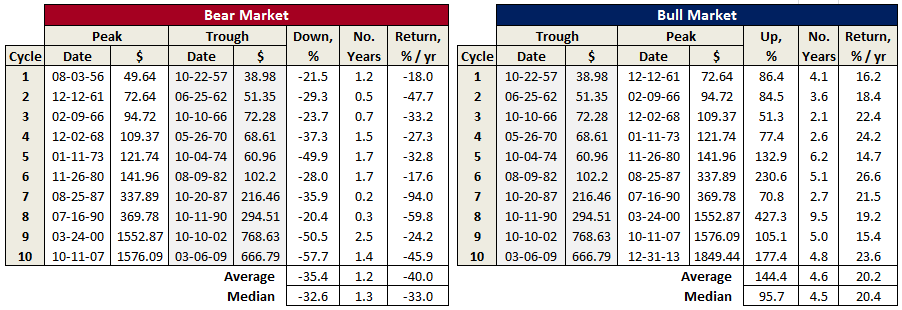

Applying this definition to the SP500 intraday price index indicates there have indeed been ten such cycles, including the current one still in process, since 1956:

The returns shown are based on price only, so exclude dividends. Note that the average duration seems to match-up pretty well with so-called “short term debt cycle” (aka business cycle) described by Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio in the charming How the Economic Machine Works – In 30 Minutes video.

Here’s break-out of bear and bull markets:

The graph below depicts the ten cycles. To provide some historic context, various events are time-lined – some good, but more bad. Return is on left axis, measured from start of cycle, so each builds where previous left off. Short-term interest rate is on right axis.

Note that each cycle resulted in a new all-time market high, which seems rather extraordinary. There were spectacular gains for the 1980 and 1990 bull markets, the latter being 427% trough-to-peak! (And folks worry lately that they may have missed-out on the current bull with its 177% gain.) Seeing the resiliency of the US market, it’s no wonder people like Warren Buffett advocate a buy-and-hold approach to investing, despite the painful -50% or more drawdowns, which have occurred three times over the period shown.

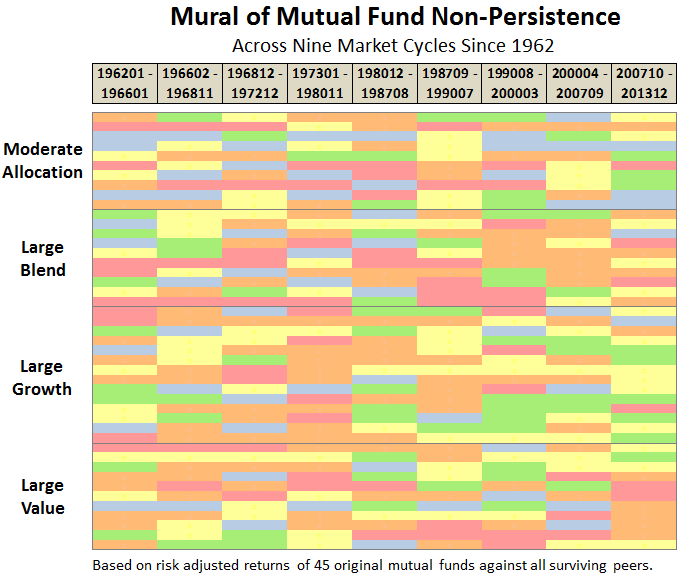

Having now defined the market cycles, which for this assessment applies principally to US stocks, we can revisit the question of mutual fund persistence (or lack of) across them.

Based on the same methodology used to determine MFO rankings, the chart below depicts results across nine cycles since 1962:

Blue indicates top quintile performance, while red indicates bottom quintile. The rankings are based on risk adjusted return, specifically Martin ratio, over each full cycle. Funds are compared against all other funds in the peer group. The number of funds was rather small back in 1962, but in the later cycles, these same funds are competing against literally hundreds of peers.

(Couple qualifiers: The mural does not account for survivorship-bias or style drift. Cycle performance is determined using monthly total returns, including any loads, between the peak-to-peak dates listed above, with one exception…our database starts Jan 62 and not Dec 61.)

Not unexpectedly, the result is similar to previous studies (eg., S&P Persistence Scorecard) showing persistence is elusive at best in the mutual fund business. None of the 45 original funds in four categories delivered top-peer performance across all cycles – none even came close.

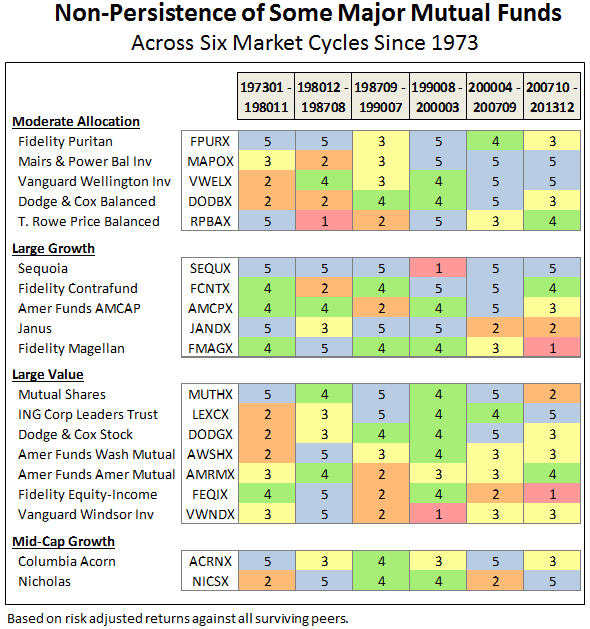

Looking at the cycles from 1973, a time when several now well know funds became established, reveals a similar lack of persistence – although one or two come close to breaking the norm. Here is a look at some of the top performing names:

MFO Great Owls Mairs & Powers Balanced (MAPOX) and Vanguard Wellington (VWELX) have enjoyed superior returns the last three cycles, but not so much in the first. The reverse is true for legendary Fidelity Magellan (FMAGX).

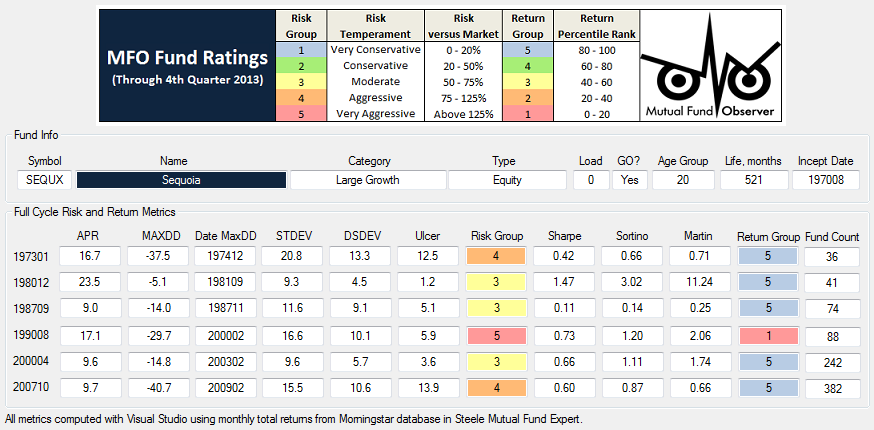

Even a fund that comes about as close to perfection as possible, Sequoia (SEQUX), swooned in the late ‘90s relative to other growth funds, like Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX), resulting in underperformance for the cycle. The table below details the risk and return metrics across each cycle for SEQUX, showing the -30% drawdown in early 2000, which marked the beginning of the tech bubble. In the next couple years, many other growth funds would do much worse.

So, while each cycle may rhyme, they are different, and even the best managed funds will inevitably spend some time in the barrel, if not fall from favor forever.

We will look to incorporate full-cycle performance data in the single-ticker MFO Risk Profile search tool. As suggested by NumbersGirl, it’s an important piece of due diligence and risk cognizance for all mutual fund investors.

26Mar14/Charles

Celebrating one-star funds, part 2!

Morningstar faithfully describes their iconic star ratings as a starting place for additional research, not as a one-stop judgment of a funds merit. As a practical matter investors do use those star ratings as part of a two-step research process:

Step One: Eliminate those one- and two-star losers

Step Two: Browse the rest

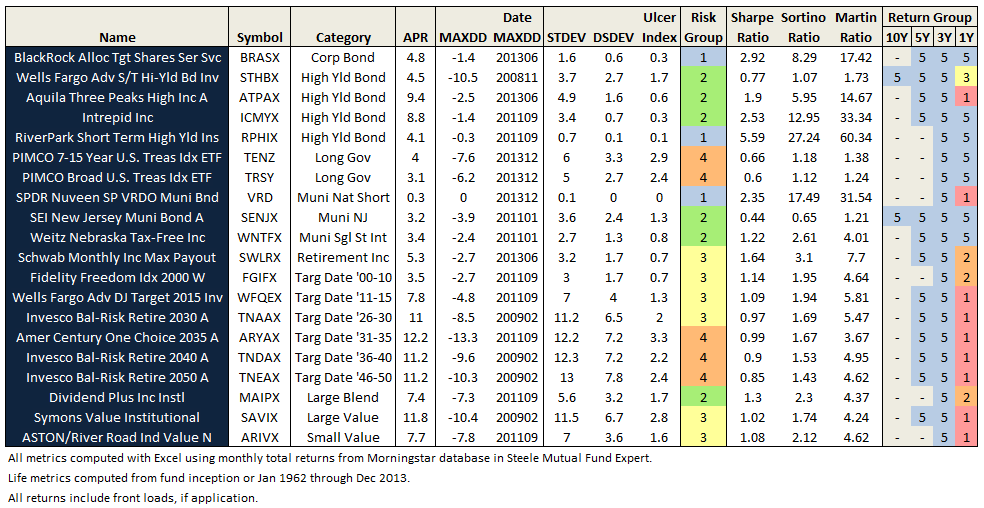

In general, there are worse strategies you could follow. Nonetheless, the star ratings can seriously misrepresent the merits of individual funds. If a fund is fundamentally misfit to its category (in March we highlighted the plight of short-term high income funds within the high-yield peer group) or if a fund is highly risk averse, there’s an unusually large chance that its star rating will conceal more than it will reveal. After a long statistical analysis, my colleague Charles concluded in last month’s issue that:

A consequence of Morningstar’s methodology is that low volatility funds with below average returns can quite possibly be out-ranked by average volatility funds with average returns. Put another way, the methodology generally penalizes funds with high volatility more so than it rewards funds with low volatility.

The Observer categorizes funds differently: our Great Owl funds are those whose risk-adjusted returns are in the top 20% of their peer group for every measurement period longer than one year. Our risk-adjustment is based on a fund’s Martin ratio which “excels at identifying funds that have delivered superior returns while mitigating drawdowns.” At base, we’ve made the judgment that investors are more sensitive to the size of a fund’s drawdown – its maximum peak to trough loss – than to the background noise of day-to-day volatility. As a result, we reward funds that provide good returns while avoiding disastrous losses.

For those interested in a second opinion, here’s the list of all one-star Great Owl funds:

- American Century One Choice 2035 A (ARYAX)

- Aquila Three Peaks High Income A (ATPAX)

- ASTON/River Road Independent Value (ARIVX)

- BlackRock Allocation Target Shares (BRASX)

- Dividend Plus Income (MAIPX)

- Fidelity Freedom Index 2000 (FGIFX)

- Intrepid Income (ICMUX)

- Invesco Balanced-Risk Retire 2030 (TNAAX)

- Invesco Balanced-Risk Retire 2040 (TNDAX)

- Invesco Balanced-Risk Retire 2050 (TNEAX)

- PIMCO 7-15 Year U.S. Treasury Index ETF (TENZ)

- PIMCO Broad U.S. Treasury Index ETF (TRSY)

- RiverPark Short Term High Yield (RPHYX)

- Schwab Monthly Income Max Payout (SWLRX)

- SEI New Jersey Municipal Bond A (SENJX)

- SPDR Nuveen S&P VRDO Municipal Bond (VRD)

- Symons Value (SAVIX)

- Weitz Nebraska Tax-Free Income (WNTFX)

- Wells Fargo Advantage Dow Jones Target 2015 (WFQEX)

- Wells Fargo Advantage Short Term High-Yield Bond (STHBX)

Are we arguing that the Great Owl metric is intrinsically better than Morningstar’s?

Nope. We do want to point out that every rating system contains biases, although we somehow pretend that they’re “purely objective.” You need to understand that the fact that a fund’s biases don’t align with a rater’s preferences is not an indictment of the fund (any more than a five-star rating should be taken as an automatic endorsement of it).

Still waiting by the phone

Last month’s celebration of one-star funds took up John Rekenthaler’s challenge to propose new fund categories which were more sensible than the existing assignments and which didn’t cause “category bloat.”

Amiably enough, we suggested short-term high yield as an eminently sensible possibility. It contains rather more than a dozen funds that act much more like aggressive short-term bond funds than like traditional high-yield bond funds, a category dominated by high-return, high-volatility funds with much longer durations.

So far, no calls of thanks and praise from the good folks in Chicago. (sigh)

How about another try: emerging markets allocation, balanced or hybrid? Morningstar’s own discipline is to separate pure stock funds (global or domestic) from stock-bond hybrid funds, except in the emerging markets. Almost all of the dozen or so emerging markets hybrid funds are categorized as, and benchmarked against, pure equity funds. Whether that advantages or disadvantages a hybrid fund at any given point isn’t the key; the question is whether it allows investors to accurately assess them. The hybrid category is well worth a test.

Who’s watching the watchers?

Presidio Multi-Strategy Fund (PMSFX) will “discontinue operations” on April 10, 2014. It’s a weird little fund with a portfolio about the size of my retirement account. This isn’t the first time we’ve written about Presidio. Presidio shared a board with Caritas All-Cap Growth (CTSAX, now Goodwood SMIDcap Discovery). In July 2013, the Board decided to liquidate Caritas. In August they reconsidered and turned both funds’ management over to Brenda Smith. At that time, I expressed annoyance with their limited sense of responsibility:

The alternative? Hire Brenda A. Smith, founder of CV Investment Advisors, LLC, to manage the fund. A quick scan of SEC ADV filings shows that Ms. Smith is the principal in a two person firm with 10 or fewer clients and $5,000 in regulated AUM.

At almost the same moment, the same Board gave Ms. Smith charge of the failing Presidio Multi-Strategy Fund (PMSFX), an overpriced long/short fund that executes its strategy through ETFs.

I wish Ms. Smith and her new investors all the luck in the world, but it’s hard to see how a Board of Trustees could, with a straight face, decide to hand over one fund and resuscitate another with huge structural impediments on the promise of handing it off to a rookie manager and declare that both moves are in the best interests of long-suffering shareholders.

By October, she was gone from Caritas but she’s stayed with Presidio to the bitter end which looks something like this:

This isn’t just a note about a tiny, failed fund. It’s a note about the Trustees of your fund boards. Your representatives. Your voice. Their failures become your failures. Their failures cause your failures.

Presidio was overseen by a rent-a-board (more politely called “a turnkey board”); a group of guys who nominally oversee dozens of unrelated funds but who have stakes in none of them. Here’s a quick snapshot of this particular board:

|

First Name |

Qualification |

Aggregate investment in the 23 funds overseen |

| Jack | Retired president of Brinson Chevrolet, Tarboro NC |

$0 |

| Michael | President, Commercial Real Estate Services, Rocky Mount, NC |

0 |

| Theo | Senior Partner, Community Financial Institutions Consulting, a sole proprietorship in Rocky Mount, NC |

0 |

| James | President, North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance, “the diversity partner of choice for Fortune 500 companies” |

0 |

| J Buckley | President, Standard Insurance and Realty, Rocky Mount NC |

0 |

The Board members are paid $2,000 per fund overseen and meet seven times a year. The manager received rather more: “For the fiscal year ended May 31, 2013, Presidio Capital Investments, LLC received fees for its services to the Fund in the amount of $101,510,” for managing a $500,000 portfolio.

What other funds do they guide? There are 22 of them:

- CV Asset Allocation Fund (CVASX);

- Arin Large Cap Theta Fund (AVOAX) managed by Arin Risk Advisors, LLC;

- Crescent Large Cap Macro, Mid Cap Macro and Strategic Income Funds managed by Greenwood Capital Associates, LLC;

- Horizons West Multi-Strategy Hedged Income Fund (HWCVX, formerly known as the Prophecy Alpha Trading Fund);

- Matisse Discounted Closed-End Fund Strategy (MDCAX) managed by Deschutes Portfolio Strategies;

- Roumell Opportunistic Value Fund (RAMVX) managed by Roumell Asset Management, LLC;

- The 11 RX funds (Dynamic Growth, Dynamic Total Return, Non Traditional, High Income, Traditional Equity, Traditional Fixed Income, Tactical Rotation, Tax Advantaged, Dividend Income, and Premier Managers);

- SCS Tactical Allocation Fund (SCSGX) managed by Sentinel Capital Solutions, Inc.;

- Sector Rotation Fund (NAVFX) managed by Navigator Money Management, Inc.; and

- Thornhill Strategic Equity Fund (TSEQX) managed by Thornhill Securities, Inc.

Oh, wait. Not quite. Crescent Mid Cap Macro (GCMIX) is “inactive.” Thornhill Strategic Equity (TSEQX)? No, that doesn’t seem to be trading either. Can’t find evidence that CV Asset Allocation ever launched. Right, right: the manager of Sector Rotation Fund (NAVFX) is under SEC sanction for “numerous misleading claims,” including reporting on the performance of the fund for periods in which the fund didn’t exist.

The bottom line: directors matter. Good directors can offer a manager access to skills, perspectives and networks that are far beyond his or her native abilities. And good directors can put their collective foot down on matters of fees, bloat and lackluster performance.

Every one of your funds has a board of directors and you really need to ask just three questions about these guys:

- What evidence is there that the directors are bringing a meaningful skill set to their post?

- What evidence is there that the directors have executed serious oversight of the management team?

- What evidence is there that the directors have aligned their interests with yours?

You need to look at two documents to answer those questions. The first is the Statement of Additional Information (SAI) which is updated every time the prospectus is. The SAI lists the board members’ qualifications, compensation, the number of funds each director oversees and the director’s investment in each of them. Here’s a general rule: if they’re overseeing dozens of funds and investing in none of them, back away. There are some very good funds that use what I refer to as rent-a-boards as a matter of administrative convenience and financial efficiency, but the use of such boards weakens a critical safeguard. If the board isn’t deeply invested, you need to see that the management team is.

The second document is called the Renewal of Investment Advisory Contract. Boards are legally required to document their due diligence and to explain to you, the folks who elected them, exactly what they looked at and what they concluded. These are sometimes freestanding documents but they’re more likely included as a section of the fund’s annual report. Look for errant nonsense, rationalizations and wishful thinking. If you find it, run away! Here’s an example of the discussion of fees charged by a one-star fund that trails 96-98% of its peers but charges a mint:

Fee Rate and Profitability – The Trustees considered that the Fund’s advisory fee is the highest in its peer group, while its expense ratio is the second highest. The Trustees considered [the manager’s] explanation that several funds included in the Fund’s peer group are passive index funds, which have extremely low fees because, unlike the Fund, they are not actively managed. The Trustees also considered [the] explanation that the growth strategy it uses to manage the Fund is extremely expensive and labor intensive because it involves reviewing and evaluating 8,000+ stocks four times a year.

Here’s the argument that the board bought: the fund has some of the highest fees in its industry but that’s okay because (1) you can’t expect us to be as cheap as an index fund and (2) we work hard, apparently unlike the 98% of funds that outperform us or charge less.

If you had an employee who was paid more and produced less than anyone else, what would you do? Then ask: “and why didn’t my board do likewise?”

It’s The Money, Stupid!

By Edward Studzinski

By Edward Studzinski

“To be clever enough to get a great deal of money, one must be stupid enough to want it.”

G.K. Chesterton

There is a repetitive scene in the movie “Shakespeare in Love” – an actor and a director are reading through one of young Master Shakespeare’s newest plays, with the ink still drying. The actor asks how a particular transition is to be made from one scene to the next. The answer given is, “I don’t know – it’s a mystery.” Much the same might be said for the process of setting and then regularly reviewing, mutual fund fees. One of my friends made the Long March with Morningstar’s Joe Mansueto from a cave deep in western China to what should now be known now as Morningstar Abbey in Chicago. She used to opine about how for commodity products like equity mutual funds, in a world of perfect competition if one believed economic theory as taught at the University of Chicago, it was rather odd that the clearing price for management fees, rather than continually coming down, seemed mired at one per cent. That comment was made almost twenty years ago. The fees still seem mired there.

One argument might be that you get what you pay for. Unfortunately many actively-managed equity funds that charge that approximately one per cent management fee lag their benchmarks. This presents the conundrum of how index funds charging five basis points (which Seth Klarman used to refer to as “mindless investing”) often regularly outperform the smart guys charging much more. The public airing of personality clashes at bond manager PIMCO makes for interesting reading in this area, but is not necessarily illuminating. For instance, allegedly the annual compensation for Bill Gross is $200M a year. However, much of that is arguably for his role in management at PIMCO, as co-chief investment officer. Some of it is for serving on a daily basis as the portfolio manager for however many funds his name is on as portfolio manager. Another piece of it might be tied to his ownership interest in the business.

The issue becomes even more confusing when you have similar, nay even almost identical, funds being managed by the same investment firm but coming through different channels, with different fees. The example to contrast here again is PIMCO and their funds with multiple share classes and different fees, and Harbor, a number of whose fixed income products are sub-advised by PIMCO and have lower fees for what appear, to the unvarnished eye, to be very similar products often managed by the same portfolio manager. A further variation on this theme can be seen when you have an equity manager running his own firm’s proprietary mutual fund for which he is charging ninety basis points in management fees while his firm is running a sleeve of another equity mutual fund for Vanguard, for which the firm is being paid a management fee somewhere between twenty and thirty basis points, usually with incentives tied to performance. And while the argument is often made that the funds may have different investment philosophies and strategies and a different portfolio manager, there is often a lot of overlap in the securities owned (using the same research process and analysts).

So, let’s assume that active equity management fees are initially set by charging what everyone else is charging for similar products. One can see by looking at a prospectus, what a competitor is charging. And I can assure you that most investment managers have a pretty good idea as to who their competitors are, even if they may think they really do not have competitors. How do the fees stay at the same level, especially as, when assets under management grow there should be economies of scale?

Ah ha! Now we reach a matter that is within the purview of the Board of Trustees for a fund or fund group. They must look at the reasonableness of the fees being charged in light of a number of variables, including investment philosophy and strategy, size of assets under management, performance, etc., etc., etc. And perhaps a principal underpinning driving that annual review and sign-off is the peer list of funds for comparison.

Probably one of the most important assignments for a mutual fund executive, usually a chief financial officer, is (a) making sure that the right consulting firm is hired to put together the peer list of similar mutual funds and (b) confirming that the consulting firm understands their assignment. To use another movie analogy, there is a scene early on in “Animal House” where during pledge week, two of the main characters visit a fraternity house and upon entering, are immediately sent to sit on a couch off in a corner with what are clearly a small group of social outliers. Peer group identification often seems to involve finding a similar group of outliers on the equivalent of that couch.

Given the large number of funds out there, one identifies a similar universe with similar investment strategies, similar in size, but mirabile dictu, the group somehow manages to have similar or inferior performance with similar or higher fees and expenses. What to do, what to do? Well of course, you fiddle with the break points so that above a certain size of assets under management in the fund, the fees are reduced. And you never have to deal with the issue that the real money is not in the break points but in fees that are too high to begin with. Perish the thought that one should use common sense and look at what Vanguard or Dodge and Cox are charging for base fees for similar products.

There is another lesson to be gained from the PIMCO story, and that is the issue of ownership structure. Here, you have an offshore owner like Allianz taking a hands-off attitude towards their investment in PIMCO, other than getting whatever revenue or income split it is they are getting. It would be an interesting analysis to see what the return on investment to Allianz has been for their original investment. It would also be interesting to see what the payback period was for earning back that original investment. And where lies the fiduciary obligation, especially to PIMCO clients and fund investors, in addition to Allianz shareholders? But that is a story for another time.

How is any of this to be of use to mutual fund investors and readers of the Observer. I am showing my age, but Vice President Hubert Humphrey used to be nick-named the “Happy Warrior.” One of the things that has become clear to me recently as David and I interview managers who have set up their own firms after leaving the Dark Side, LOOK FOR THE HAPPY WARRIORS. For them, it is not the process of making money. They don’t need the money. Rather they are doing it for the love of investing. And if nobody comes, they will still do it to manage their own money. Avoid the ones for whom the money has become an addiction, a way of keeping score. For supplementary reading, I commend to all an article that appeared in the New York Sunday Times on January 19, 2014 entitled “For the Love of Money” by Sam Polk. As with many of my comments, I am giving all of you more work to do in the research process for managing your money. But you need to do it if you serious about investing. And remember, character and integrity always show through.

And those who can’t teach, teach gym (part 2)

Beginning in 1997, the iconically odd-looking Jim Jubak wrote the wildly-popular “Jubak’s Picks” column for MSN Money. In 2010, he apparently decided that investment management looked awfully easy and so launched his own fund.

Beginning in 1997, the iconically odd-looking Jim Jubak wrote the wildly-popular “Jubak’s Picks” column for MSN Money. In 2010, he apparently decided that investment management looked awfully easy and so launched his own fund.

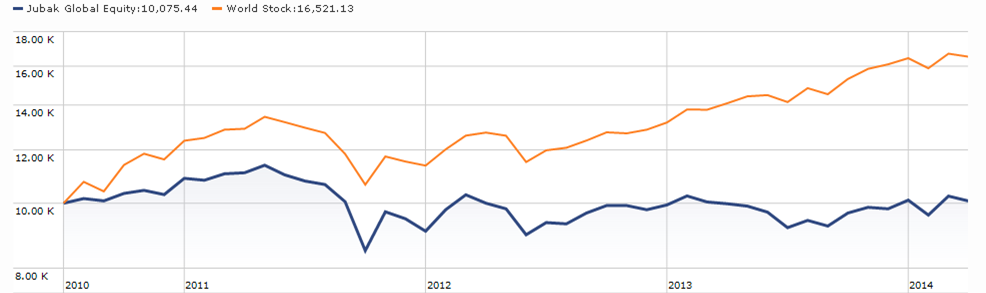

Which stunk. Over the three years of its existence, it’s trailed 99% of its peers. And so the Board of Trustees of the Trust has approved a Plan of Liquidation which authorizes the termination, liquidation and dissolution of the Jubak Global Equity Fund (JUBAX). The Fund will be T, L, and D’d on or about May 29, 2014. (It’s my birthday!)

Here’s the picture of futility, with Mr. Jubak on the blue line and mediocrity represented by the orange one:

Yup, $16 million in assets – none of it representing capital gains.

Mr. Jubak joins a long list of pundits, seers, columnists, prognosticators and financial porn journalists who have discovered that a facility for writing about investments is an entirely separate matter from any ability to actually make money.

Among his confreres:

Robert C. Auer, founder of SBAuer Funds, LLC, was from 1996 to 2004, the lead stock market columnist for the Indianapolis Business Journal “Bulls & Bears” weekly column, authoring over 400 columns, which discussed a wide range of investment topics. As manager of Auer Growth (AUERX), he’s turned a $10,000 investment into $8500 over the course of six years.

Jonathan Clements left a high visibility post at The Wall Street Journal to become Director of Financial Education, Citi Personal Wealth Management. Sounds fancy. Frankly, it looks like was relegated to “blogger.” Mr. Clements recently announced his return to journalism, and the launch of a weekly column in the WSJ.

John Dorfman, a Bloomberg and Wall Street Journal columnist, launched Dorfman Value Fund which finally became Thunderstorm Value Fund (THUNX). Having concluded that low returns, high expenses, a one-star rating, and poor marketing aren’t the road to riches, the advisor recommended that the Board close (on January 17, 2012) and liquidate (on February 29, 2012) the fund.

Ron Insana, who left CNBC in 2006 to form a hedge fund and returned to part-time punditry three years later. He’s currently (March 28, 2014) prognosticating “a very nasty pullback” in the stock market.

Scott Martin, a contributor to FOX Business Network and a former columnist with TheStreet.com, co-managed Astor Long/Short ETF Fund (ASTLX) for one undistinguished year before moving on.

Steven J. Milloy, “lawyer, consultant, columnist, adjunct scholar,” managed the somewhat looney Free Enterprise Action Fund which merged with the somewhat looney $12 million Congressional Effect Fund (CEFFX), which never hired Mr. Milloy and just fired Congressional Effect Management.

Observer Fund Profiles

Each month the Observer provides in-depth profiles of between two and four funds. Our “Most Intriguing New Funds” are funds launched within the past couple years that most frequently feature experienced managers leading innovative newer funds. “Stars in the Shadows” are older funds that have attracted far less attention than they deserve.

During March, Bro. Studzinski and I contacted a quartet of distinguished managers whose careers were marked by at least two phases: successfully managing large funds within a fund complex and then walking away to launch their own independent firms. We wanted to talk with them both about their investing disciplines and current funds and about their bigger picture view of the world of independent managers.

Our lead story in May carries the working title, “Letter to a Young Fund Manager.” We are hoping to share some insight into what it takes to succeed as a boutique manager running your own firm. Our hope is that the story will be as useful for folks trying to assess the role of small funds in their portfolio as it will be to the (admittedly few) folks looking to launch such funds.

As a preview, we’d like to introduce the four managers and profile their funds:

Evermore Global Value (EVGBX): David Marcus was trained by Michael Price, managed Mutual European and co-managed two other Mutual Series funds, then spent time investing in Europe before returning to launch this remarkably independent “special situations” fund.

Huber Equity Income (HULIX): Joe Huber designed and implemented a state of the art research program at Hotchkis and Wiley and managed their Value Opportunities fund for five years before striking out to launch his own firm and, coincidentally, launched two of the most successful funds in existence.

Poplar Forest Partners (PFPFX): Dale Harvey is both common and rare. He was a very successful manager for five American Funds who was disturbed by their size. That’s common. So he left, which is incredibly rare. One of the only other managers to follow that path was Howard Schow, founder of the PrimeCap funds.

Walthausen Select Value (WSVRX): John Walthausen piloted both Paradigm Value and Paradigm Select to peer-stomping returns. He left in 2007 to create his own firm which advises two funds that have posted, well, peer stomping returns.

Launch Alert: Artisan High Income (ARTFX)

On March 19th, Artisan launched their first fixed-income fund. The plan is for the manager to purchase a combination of high-yield bonds and other stuff (technically: “secured and unsecured loans, including, without limitation, senior and subordinated loans, delayed funding loans and revolving credit facilities, and loan participations and assignments”). There’s careful attention given to the quality and financial strength of the bond issuer and to the magnitude of the downside risks. The fund might invest globally.

The Fund is managed by Bryan C. Krug. For the past seven years, Mr. Krug has managed Ivy High Income (WHIAX). His record there was distinguished, especially for his ability to maneuver through – and profit from – a variety of market conditions. A 2013 Morningstar discussion of the fund observes, in part:

[T]he fund’s 26% allocation to bonds rated CCC and below … is well above the 15% of its typical high-yield bond peer. Recently, though, Krug has been taking a somewhat defensive stance; he increased the amount of bank loans to nearly 34% as of the end of 2012, well above the fund’s 15% target allocation … Those kinds of calls have allowed the fund to mitigate losses well–performance in 2011’s third quarter and May 2012 are ready examples–as well as to deliver strong results in a variety of other environments. That record and relatively low expenses make for a compelling case here.

$10,000 invested at the beginning of Mr. Krug’s tenure would have grown to $20,700 by the time of his departure versus $16,700 at his average peer. The Ivy fund was growing by $3 – 4 billion a year, with no evident plans for closure. While there’s no evidence that asset bloat is what convinced Mr. Krug to look for new opportunities, indeed the fund continued to perform splendidly even at $11 billion, a number of other managers have shifted jobs for that very reason.

The minimum initial investment is $1000 for the Investor class and $250,000 for Advisor shares. Expenses for both the Investor and Advisor classes are capped at 1.25%.

Artisan’s hiring standard has remained unchanged for decades: they interview dozens of management teams each year but hire only when they think they’ve found “category killers.” With 10 of their 12 rated funds earning four- or five-stars, they seem to achieve that goal. Investors seeking a cautious but opportunistic take on high income investing really ought to look closer.

Funds in Registration

New mutual funds must be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission before they can be offered for sale to the public. The SEC has a 75-day window during which to call for revisions of a prospectus; fund companies sometimes use that same time to tweak a fund’s fee structure or operating details.

Funds in registration this month are eligible to launch in late May or early June 2014 and some of the prospectuses do highlight that date.

This month David Welsch tracked down five funds in registration, the lowest totals since we launched three years ago. Curious.

Manager Changes

On a related note, we also tracked down 43 sets of fund manager changes. The most intriguing of those include Amit Wadhwaney’s retirement from managing Third Avenue International Value (TAVIX) and Jim Moffett’s phased withdrawal from Scout International (UMBWX).

Updates

Our friends at RiverRoad Asset Management report that they have entered a “strategic partnership” with Affiliated Managers Group, Inc. RiverRoad becomes AMG’s 30th partner. The roster also includes AQR, Third Avenue and Yacktman. As part of this agreement, AMG will purchase River Road from Aviva Investors. Additionally, River Road’s employees will acquire a substantial portion of the equity of the business. The senior professionals at RiverRoad have signed new 10-year employment agreements. They’re good people and we wish them well.

Our friends at RiverRoad Asset Management report that they have entered a “strategic partnership” with Affiliated Managers Group, Inc. RiverRoad becomes AMG’s 30th partner. The roster also includes AQR, Third Avenue and Yacktman. As part of this agreement, AMG will purchase River Road from Aviva Investors. Additionally, River Road’s employees will acquire a substantial portion of the equity of the business. The senior professionals at RiverRoad have signed new 10-year employment agreements. They’re good people and we wish them well.

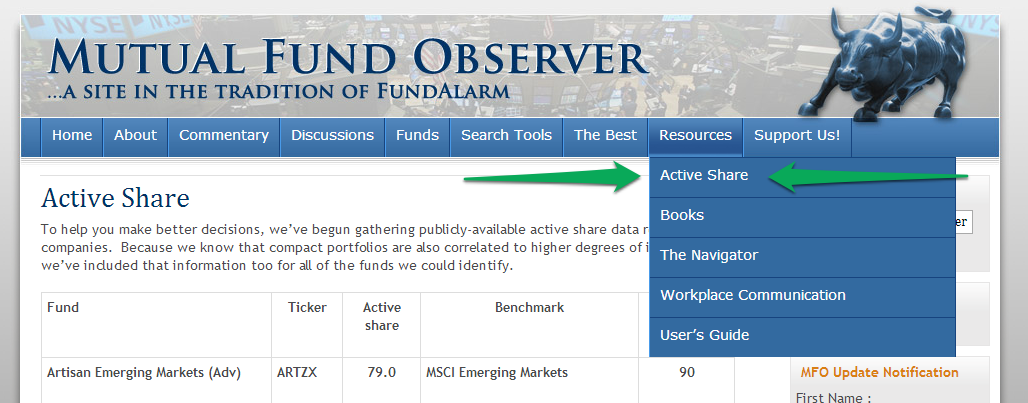

Even more active share.

Last month we shared a list of about 50 funds who were willing to report heir current active share, a useful measure that allows investors to see how independent their funds are of the index. We offered folks the chance to be added to the list. A dozen joined the list, including folks from Barrow, Conestoga, Diamond Hill, DoubleLine, Evermore, LindeHanson, Pinnacle, and Poplar Forest. We’ve given our active share table a new home.

ARE YOU ACTIVE? WOULD YOU LIKE SOMEONE TO NOTICE?

We’ve been scanning fund company sites, looking for active share reports. If we’ve missed you, we’re sorry. Help us correct the oversight by sending us the link to where you report your active share stats. We’d be more than happy to offer a permanent home for the web’s largest open collection of active share data.

Briefly Noted . . .

For reasons unexplained, GMO has added a “purchase premium” (uhhh… sales load?) and redemption fee of between 8 and 10 basis points to three of its funds: GMO Strategic Fixed Income Fund (GMFIX), GMO Global Developed Equity Allocation Fund (GWOAX) and GMO International Developed Equity Allocation Fund (GIOTX). Depending on the share class, the GMO funds have investment minimums in the $10 million – $300 million range. At the lower end, that would translate to an $8,000 purchase premium. At the high end, it might be $100,000.

Effective April 1, 2014, the principal investment strategy of the Green Century Equity Fund (GCEQX) will be revised to change the index tracked by the Fund, so as to exclude the stocks of companies that explore for, process, refine or distribute coal, oil or gas.

SMALL WINS FOR INVESTORS

The Board of Mainstay Marketfield Fund (MFLDX) has voted to slash the management fee (slash it, I say!) by one basis point! So, in compensation for a sales load (5.75% for “A” shares), asset bloat (at $21 billion, the fund has put on nearly $17 billion since being acquired by New York Life) and sagging performance (it still leads its long/short peer group, but by a slim margin), you save $1 – every year – for every $10,000 you invest. Yay!!!!!

CLOSINGS (and related inconveniences)

Robeco Boston Partners Long/Short Research Fund (BPRRX) closed on a day’s notice at the end of March, 2014 because of “a concern that a significant increase in the size of the Fund may adversely affect the implementation of the Fund’s strategy.” The advisor long-ago closed its flagship Robeco Boston Partners Long/Short Equity (BPLEX) fund. At the beginning of January 2014 they launched a third offering, Robeco Boston Partners Global Long/Short (BGLSX) which is only available to institutional investors.

Effective as of the close of business on March 28, 2014, Perritt Ultra MicroCap Fund (PREOX) closed to new investors.

OLD WINE, NEW BOTTLES

On March 31, Alpine Innovators Fund (ADIAX) became Alpine Small Cap Fund. It also ceased to be an all-cap growth fund oriented toward stocks benefiting from the “innovative nature of each company’s products, technology or business model.” It was actually a pretty reasonable fund, not earth-shattering but decent. Sadly, no one cared. It’s not entirely clear that they’re going to swarm on yet another small-blend fund. The upside is that the new managers have a stint with Lord Abbett Small Cap Blend Fund

Effective on or about April 28, 2014, BNY Mellon Small/Mid Cap Fund‘s (MMCIX) name will be changed to BNY Mellon Small/Mid Cap Multi-Strategy Fund and they’ll go all multi-manager on you.

Effective March 21, 2014, the ticker for the Giant 5 Total Investment System changed from FIVEX to CASHX. Cute. The board had previously approved replacement of the phrase “Giant 5” with “Index Funds” (no, really), but that hasn’t happened yet.

At the end of April, 2014, Goldman Sachs has consented to modestly shorten the names of some of their funds.

|

Current Fund Name |

New Fund Name |

|

| Goldman Sachs Structured International Tax-Managed Equity Fund | Goldman Sachs International Tax-Managed Equity Fund | |

| Goldman Sachs Structured Tax-Managed Equity Fund | Goldman Sachs U.S. Tax-Managed Equity Fun |

They still don’t fit on one line.

Johnson Disciplined Mid-Cap Fund (JMDIX) is slated to become Johnson Opportunity on May 1, 2014. At that point, it won’t be restricted to investing in mid-cap stocks anymore. Good thing, too, since they’re only … how to say this? Intermittently excellent at that discipline.

On May 5, Laudus Mondrian Global Fixed Income Fund (LMGDX) becomes Laudus Mondrian Global Government Fixed Income Fund. It’s already 90% in government bonds, so the change is mostly symbolic. At the same time, Laudus Mondrian International Fixed Income Fund (LIFNX) becomes Laudus Mondrian International Government Fixed Income Fund. It, too, invests now in government bonds.

Effective March 17, 2014, Mariner Hyman Beck Fund (MHBAX) was renamed the Mariner Managed Futures Strategy Fund.

OFF TO THE DUSTBIN OF HISTORY

Effective on or about May 16, 2014, AllianzGI Disciplined Equity Fund (ARDAX) and AllianzGI Dynamic Emerging Multi-Asset Fund (ADYAX) will be liquidated and dissolved. The former is tiny and mediocre, the latter tinier and worse. Hasta!

Avatar Capital Preservation Fund (ZZZNX), Avatar Tactical Multi-Asset Income Fund (TAZNX), Avatar Absolute Return Fund (ARZNX) and Avatar Global Opportunities Fund (GOWNX) – pricey funds-of-ETFs – ceased operations on March 28, 2014.

Epiphany FFV Global Ecologic Fund (EPEAX) has closed to investors and will be liquidated on April 28, 2014.

Goldman Sachs China Equity Fund (GNIAX) is being merged “with and into” the Goldman Sachs Asia Equity Fund (GSAGX). The SEC filing mumbled indistinctly about “the second quarter of 2014” as a target date.

The $200 million Huntington Fixed Income Securities Fund (HFIIX) will be absorbed by the $5.6 billion Federated Total Return Bond Fund (TLRAX), sometime during the second quarter of 2014. The Federated fund is pretty consistently mediocre, and still the better of the two.

On March 17, 2014, Ivy Asset Strategy New Opportunities Fund merged into Ivy Emerging Markets Equity Fund (IPOAX, formerly Ivy Pacific Opportunities Fund). On the same day, Ivy Managed European/Pacific Fund merged into Ivy Managed International Opportunities Fund (IVTAX). (Run away! Go buy a nice index fund!)

The $2 billion, four-star Morgan Stanley Focus Growth Fund (OMOAX) is merging with $1.3 billion, four-star Morgan Stanley Institutional Growth (MSEGX) at the beginning of April, 2014. They are, roughly speaking, the same fund.

Parametric Currency Fund (EAPSX), $4 million in assets, volatile and unprofitable after two and a half years – closed on March 25, 2014 and was liquidated a week later.

Pax World Global Women’s Equality Fund (PXWEX) is slated to merged into a newly-formed Pax Global Women’s Index Fund.

On February 25, 2014, the Board of Trustees of Templeton Global Investment Trust on behalf of Templeton Asian Growth Fund approved a proposal to terminate and liquidate Templeton Asian Growth Fund (FASQX). The liquidation is anticipated to occur on or about May 20, 2014. I’m not sure of the story. It’s a Mark Mobius production and he’s been running offshore versions of this fund since the early 1990s. This creature, launched about four years ago, has been sucky performance and negligible assets.

Turner Emerging Markets Fund (TFEMX) is being liquidated on or about April 15, 2014. Why? “This decision was made after careful consideration of the Fund’s asset size, strategic importance, current expenses and historical performance.” Historical performance? What historical performance? Turner launched this fund in August of 2013. Right. After six months Turner pulled the plug. Got long-term planning there, guys!

In Closing . . .

Happy anniversary to us all. With this issue, the Observer celebrates its third anniversary. In truth, we had no idea of what we were getting into but we knew we had a worthwhile mission and the support of good people.

We started with a fairly simple, research-based conviction: bloated funds are not good investments. As funds swells, their investible universes contract, their internal incentives switch from investment excellence to avoiding headline risk, and their reward systems shift to reward asset growth and retention. They become timid, sclerotic and unrewarding.

To be clear, we know of no reason which supports the proposition that bigger is better, most especially in the case of funds that place some or all of their portfolios in stocks. And yet the industry is organized, almost exclusively, to facilitate such beasts. Independent managers find it hard to get attention, are disadvantaged when it comes to distribution networks, and have almost no chance of receiving analyst coverage.

We’ve tried to be a voice for the little guy. We’ve tried to speak clearly and honestly about the silly things that you’re tempted into doing and the opportunities that you’re likely overlooking. So far we’ve reached over 300,000 readers who’ve dropped by for well over a million visits. Which is pretty good for a site with neither commercial endorsements or pictures of celebrities in their swimwear.

In the year ahead, we’ll try to do better. We’re taking seriously our readers’ recommendation. One recommendation was to increase the number of fund profiles (done!) and to spend more time revisiting some of the funds we’ve previously written about (done!). As we reviewed your responses to “what one change could we make to better serve you” question, several answers occurred over and over:

- People would like more help in assembling portfolios, perhaps in form of model portfolios or portfolio templates. A major goal for 2014, then, is working more with our friends in the industry to identify useful strategies for allowing folks to identify their own risk/return preferences and matching those to compatible funds. We need to be careful since we’re not trained as financial advisors, so we want to offer models and illustrations rather than pretend to individual advice.

- People would like more guidance on the resources already on-site. We’ve done a poor job in accommodating the fact that we see about 10,000 first-time visitors each month. As a result, people aren’t aware that we do maintain an archive of every audio-recording of our conference calls (check the Funds tab, then Featured Funds), and do have lists of recommended books (Resources -> Books!) and news sources (Best of the Web). And so one of our goals for the year ahead is to make the Observer more transparent and more easily navigable.

- Many people have asked about mid-month updates, at least in the case of closures or other developments which come with clear deadlines. We might well be able to arrange to send a simple email, rarely more than once a month, if something compelling breaks.

- Finally, many people asked for guidance for new investors.

Those are all wonderfully sensible suggestions and we take them very seriously. Our immediate task is to begin inventorying our resources and capabilities; we need to ask “what’s the best we can do with what we’ve got today?” And “how can we work to strengthen our organizational foundation, so that we can help more?”

Those are great questions and we very much hope you join us as we shape the answers in the year ahead.

Finally, I’ll note that I’m shamefully far behind in extending thanks to the folks who’ve contributed to the Observer – by check or PayPal – in the past month. I’ve launched on a new (and terrifying) adventure in home ownership; I spent much of the past month looking at houses in Davenport with the hopes of having a place by May 1. I’m about 250 sets of signatures and initials into the process, with just one or two additional pallets of scary-looking forms to go! Pray for me.

And thanks to you all.